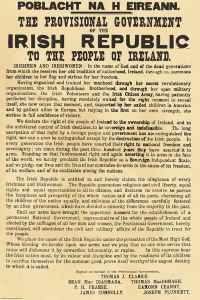

Na Fianna Éireann (The Fianna of Ireland), known as the Fianna (“Soldiers of Ireland”), an Irish nationalist youth organization, is founded by Constance Markievicz on August 16, 1909, with later help from Bulmer Hobson. Fianna members are involved in setting up the Irish Volunteers and have their own circle of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). They take part in the 1914 Howth gun-running and, as Volunteer members, in the 1916 Easter Rising. They are active in the Irish War of Independence, and many take the anti-Treaty side in the Irish Civil War.

An earlier “Fianna” is organised “to serve as a Junior Hurling League to promote the study of the Irish Language” on June 26, 1902, at the Catholic Boys’ Hall, Falls Road, in West Belfast, the brainchild of Bulmer Hobson. Hobson, a Quaker influenced by suffragism and nationalism, joins the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1904 and is an early member of Sinn Féin during its monarchist-nationalist period, alongside Arthur Griffith and Constance Markievicz. Hobson later relocates to Dublin and the Fianna organisation collapses in Belfast. Markievicz, inspired by the rapid growth of Robert Baden-Powell‘s Boy Scouts, forms sometime before July 1909 the Red Branch Knights, a Dublin branch of Irish National Boy Scouts. After discussions involving Hobson, Markievicz, suffragist and labour activist Helena Molony and Seán McGarry, the Irish National Boy Scouts change their name to Na Fianna Éireann at a meeting in 34 Lower Camden Street, Dublin, on August 16, 1909, at which Hobson is elected as president, thus ensuring a strong IRB influence, Markievicz as vice-president and Pádraig Ó Riain as secretary. Seán Heuston is the leader of the Fianna on Dublin’s north side, while Cornelius “Con” Colbert is the leader on the south side. The Fianna forms as a Nationalist alternative to Powell’s Scouts with the aim to achieve the full independence of Ireland by training and teaching scouting and military exercises, Irish history, and the Irish language.

The Fianna finds its first years difficult and by 1912 has barely 1,000 members and a skeleton structure outside of the cities of Dublin, Cork, Belfast and Galway. But in the next couple of years the momentum of events carries the Fianna forward. It is involved in initiating the militarisation of the IRB, the launch of the Irish Volunteers and showing solidarity with the striking Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). It is also crucial to the success of the Howth and Kilcoole gun-running operations. Alongside these headline-grabbing activities, the Fianna continues with classes, drilling, camps and protests and reaps the benefits of an expanding membership and structure. When the fighting starts, the Fianna are not found wanting either. In 1916, Na Fianna members are present in all areas that mobilise and fight alongside all the other Republican organisations. They continue to fight throughout the Irish War of Independence and Irish Civil War. Seeing comrades being killed in action or executed or suffering imprisonment does not dim their enthusiasm for the fight. In Na Fianna Éireann’s March 1922 Árd Fheis, the 187 delegates representing 30,000 members vote unanimously to reject the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The Fianna are declared an illegal organisation by the government of the Irish Free State in 1931. This is reversed when Fianna Fáil comes to power in 1932 but re-introduced in 1938. During the splits in the Republican movement of the later part of the 20th century, the Fianna and Cumann na mBan support Provisional Sinn Féin in 1969 and Republican Sinn Féin in 1986. The Fianna have been a proscribed organisation in Northern Ireland since 1920.

While the events in which the Fianna members are involved over the revolutionary years have a special place in Irish history, the specific role of the Fianna is absent from most written histories. This, allied with the failure to adequately commemorate the organisation’s centenary, marks a kind of revisionism of omission.