A lesser-known Irish Brigade of the American Civil War, the 6th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, is mustered into Confederate service at Camp Moore on June 4, 1861. It is part of the Louisiana Tigers. At a time when an estimated 20,000 Irish live in New Orleans, it is not surprising that the 6th Louisiana comprises a high percentage of Irish soldiers. It begins its service with 916 men and ends with 52 after surrendering after the Battle of Appomattox Court House in April 1865.

The regiment’s 916 men are organized into 10 companies designated with the letters A–I and K. Most of the companies are organized in Orleans Parish, although Company D is from Tensas Parish, Company C from St. Landry Parish, and Company A from Union Parish and Sabine Parish. The unit’s first colonel is Isaac Seymour, its first lieutenant colonel is Louis Lay, and its first major is Samuel L. James. Over half of the unit’s men with known places of birth are born outside of the United States, primarily from Ireland. In its early days, the unit has a reputation for being disorderly and hard to control. Seymour has to publicly rebuke several officers in late 1861 for drunkenness.

Sent to the fighting in Virginia and stationed at Centreville, the regiment guards supplies and is not involved in the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. In August, it is added to a brigade commanded by William H. T. Walker consisting of the 7th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, the 8th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, the 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, and the 1st Louisiana Special Battalion. The brigade spends the next winter in the vicinity of Centreville, and Orange Court House before being transferred to the Shenandoah Valley in early 1862, where it fights under Stonewall Jackson. James resigns on December 1, 1861, and is replaced by George W. Christy, who is dropped from the regiment’s rolls on May 9, 1862, and replaced with Arthur MacArthur. Lay resigns on February 13 and is replaced by Henry B. Strong.

On May 23, 1862, the regiment sees action in the Battle of Front Royal and captures two Union battle flags in a skirmish at Middletown the next day. May 25 sees the regiment engage in the First Battle of Winchester, where MacArthur is killed, and on June 9 it fights in the Battle of Port Republic, in which 66 of its men are killed or wounded. MacArthur’s role as major is then filled by Nathaniel G. Offutt. After Port Republic, Jackson’s men are transferred to the Virginia Peninsula to take part in the Seven Days Battles, and the 6th Louisiana skirmishes at Hundley’s Corner on June 26 before fighting in the Battle of Gaines’ Mill the next day. Seymour leads the brigade at Gaines’ Mill, since Richard Taylor is ill. The Louisianans, known as the Louisiana Tigers, become bogged down in Boatswain’s Swamp, are repulsed with loss, and withdraw from the battle. Seymour is killed during the charge and is replaced by Strong. Offutt takes over Strong’s position as lieutenant colonel, and William Monaghan becomes colonel.

Moving north with Jackson in August, the regiment fights in the Manassas Station Operations at Bristoe Station, Virginia on August 26 and Kettle Run, Virginia the following day. At Kettle Run, the regiment holds off a Union advance while the 8th Louisiana burns a bridge, and then the two regiments, joined by the 60th Georgia Infantry Regiment and the 5th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, fight against the Union Army‘s Excelsior Brigade and the brigade of Colonel Joseph Bradford Carr. It then fights in the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 29-30, 1862. At Second Bull Run, it is part of the brigade of Colonel Henry Forno. On the first day of the battle, Forno’s brigade helps repulse James Nagle‘s Union brigade. On the morning on 30 August 30, it is sent to the rear for supplies and does not rejoin the fighting that day.

After Second Bull Run, the 6th Louisiana fights in the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862, where the Louisiana brigade is routed with the 5th, 6th, 8th, and 14th Louisiana regiments suffering the heaviest casualties in the Confederate army, and on September 17 sees action in the Battle of Antietam. At Antietam, the regiment is part of Harry T. Hays‘s brigade. During the fighting, Hays’s brigade charges toward the Miller’s Cornfield and is cut to pieces, with the brigade suffering 61 percent casualties. The 6th Louisiana loses 52 men killed or wounded, including Colonel Strong, who is killed and replaced with Offutt. All 12 officers of the 6th Louisiana that see action at Antietam are killed or wounded. Monaghan becomes lieutenant colonel and is replaced as major by Joseph Hanlon. Offutt in turn resigns on November 7 and is replaced by Monaghan. Hanlon becomes lieutenant colonel, and Manning is promoted to major. The regiment is held in reserve at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, and is not directly engaged, although it does come under Union artillery fire.

An inspection in January 1863 rates the 6th Louisiana as having “poor” discipline and moderately good at performance in drills. Along with the 5th Louisiana Infantry, the regiment contests a Union crossing of the Rappahannock River on April 29, 1863. Union troops are able to force a crossing, and the 6th Louisiana has 7 men killed, 12 wounded, and 78 captured. It then fights in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg on May 3, 1863, where 27 of the unit’s men are captured. While part of the regiment is captured, most of the unit is able to withdraw from the field in better condition than the other Confederate units positioned near it. It then fights at the Battle of Salem Church the next day. Altogether, the 6th Louisiana Infantry sustains losses of 14 killed, 68 wounded, and 99 captured at the Battle of Chancellorsville. It next sees combat on June 14, 1863, in the Second Battle of Winchester, where it joins its brigade of other Louisiana units in capturing a Union fort.,

At the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1-3, 1863, the 6th Louisiana is still in Hays’ brigade. On July 1, the brigade is part of a Confederate charge that sweeps the Union XI Corps from the field, although it is less heavily engaged than some of the other participating Confederate brigades. Entering the town of Gettysburg, the brigade captures large numbers of disorganized Union troops. On the evening of the following day, the brigade is part of a failed attack against the Union position on Cemetery Hill. It then spends July 3, the final day of the battle, skirmishing. The Confederates, who are defeated at Gettysburg, withdraw from the field on July 4. The regiment takes 232 men into the fighting at Gettysburg and suffers 61 casualties.

Back in Virginia, the 6th Louisiana fights in the Bristoe campaign in October 1863 and is overrun in the Second Battle of Rappahannock Station on November 7, losing 89 men captured. In the spring of 1864, it fights in Ulysses S. Grant‘s Overland Campaign. On May 5, 1864, in the Battle of the Wilderness, the regiment helps repulse a Union attack, after Hays’ brigade had been repulsed and badly bloodied earlier in the battle. It then fights in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House on May 9-19, 1864. On May 12, the regiment is part of its brigade’s fighting at the Mule Shoe. The brigade is badly wrecked at the Mule Shoe, and only 60 men are present at the 6th Louisiana’s roll call the next morning. From June through October, it is detached as part of Jubal Early‘s command to fight in the Valley campaigns of 1864. Monaghan is killed in battle in late August and is not replaced as colonel. At the Battle of Cedar Creek in October 1864, one company of the 6th Louisiana sees both men present shot. After the battle, the 5th, 6th, and 7th are consolidated into a single company when the brigade is reorganized due to severe losses. Taking part in the Siege of Petersburg, the 6th Louisiana’s survivors fight at the Battle of Hatcher’s Run on February 6, 1865, and at the Battle of Fort Stedman on March 25.

The 6th Louisiana’s remnants end their military service when Robert E. Lee‘s Confederate army surrenders on April 9, after the Battle of Appomattox Court House. At the time of the surrender, the 6th Louisiana has been reduced to 52 officers and men. Over the course of its existence, 1,146 men serve in the unit. Of that total, 219 are combat deaths, 104 die of disease, one man drowns, five die accidentally, one man is executed, and at least 232 desert. Desertions are particularly heavy in three companies that primary consist of men born outside of the United States.

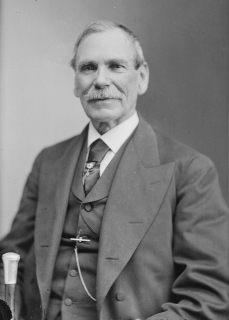

(Pictured: National colors of the “Orleans Rifles” or Company H, Sixth Louisiana Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War)