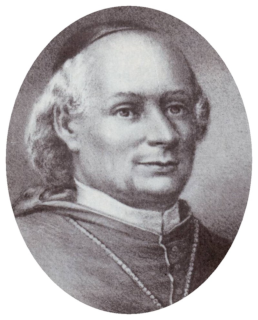

Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, an Italian Roman Catholic archbishop in the mid-seventeenth century, returns to Rome on February 23, 1649, after spending just over three years in Ireland supporting Catholics with arms, money, and diplomacy.

Rinuccini is born in Rome on September 15, 1592. He is educated by the Jesuits in Rome and studies law at the Universities of Bologna and Perugia. In due course, he is ordained a priest, having at the age of twenty-two obtained his doctor’s degree from the University of Pisa. He is named a camariere (chamberlain) by Pope Gregory XV and in 1625 becomes Archbishop of Fermo. In 1631 he carefully refuses an offer to be made Archbishop of Florence.

On September 15, 1644, a new pope, Pope Innocent X, is elected. He decides to step up the help for the Irish Catholic Confederates. He sends Rinuccini as nuncio to Ireland to replace the envoy Friar Pierfrancesco Scarampi, who had been sent to Ireland by his predecessor, Pope Urban VIII, in 1643.

Rinuccini departs France from Saint-Martin-de-Ré near La Rochelle on October 18, 1645, on the frigate San Pietro and arrives in Kenmare, County Kerry, on October 21, 1645, with a retinue of twenty-six Italians, several Irish officers, and the Confederation’s secretary, Richard Bellings. He proceeds to Kilkenny, the Confederate capital, where Richard Butler, 3rd Viscount Mountgarret, the president of the Confederation, receives him at the castle. He speaks Latin to Montgarret, but all the official business of the Confederates is done in English. He asserts in his discourse that the object of his mission is to sustain the King, but above all to help the Catholic people of Ireland in securing the free and public exercise of their religion, and the restoration of the churches and church property to the Catholic Church.

Rinuccini had sent ahead arms and ammunition: 1,000 braces of pistols, 4,000 cartridge belts, 2,000 swords, 500 muskets and 20,000 pounds of gunpowder. He arrives twelve days later with a further two thousand muskets and cartridge-belts, four thousand swords, four hundred braces of pistols, two thousand pike-heads, and twenty thousand pounds of gunpowder, fully equipped soldiers and sailors and 150,658 livres tournois to finance the Irish Catholic war effort. These supplies give him a huge input into the Confederate’s internal politics because he doles out the money and arms for specific military projects, rather than handing them over to the Confederate government, or Supreme Council.

Rinuccini hopes that by doing so he can influence the Confederates’ strategic policy away from making a deal with Charles I and the Royalists in the English Civil War and towards the foundation of an independent Catholic-ruled Ireland. In particular, he wants to ensure that churches and lands taken in the rebellion would remain in Catholic hands. This is consistent with what happened in Catholic-controlled areas during the Thirty Years’ War in Germany. His mission can be seen as part of the Counter-Reformation in Europe. He also has unrealistic hopes of using Ireland as a base to re-establish Catholicism in England. However, apart from some military successes such as the Battle of Benburb on June 5, 1646, the main result of his efforts is to aggravate the infighting between factions within the Confederates.

The Confederates’ Supreme Council is dominated by wealthy landed magnates, predominantly of “Old English” origin, who are anxious to come to a deal with the Stuart monarchy that will guarantee them their land ownership, full civil rights for Catholics, and toleration of Catholicism. They form the moderate faction, which is opposed by those within the Confederation, who want better terms, including self-government for Ireland, a reversal of the land confiscations of the plantations of Ireland and establishment of Catholicism as the state religion. A particularly sore point in the negotiations with the English Royalists is the insistence of some Irish Catholics on keeping in Catholic hands the churches taken in the war. Rinuccini accepts the assurances of the Supreme Council that such concerns will be addressed in the peace treaty negotiated with James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormond, negotiated in 1646, now known as the First Ormond Peace.

However, when the terms are published, they grant only the private practice of Catholicism. Alleging that he had been deliberately deceived, Rinuccini publicly backs the militant faction, which includes most of the Catholic clergy and some Irish military commanders such as Owen Roe O’Neill. On the other side there are the Franciscans Pierre Marchant, and later Raymond Caron. In 1646, when the Supreme Council tries to get the Ormond Peace ratified, Rinuccini excommunicates them and helps to get the Treaty voted down in the Confederate General Assembly. The Assembly has the members of the Supreme Council arrested for treason and elects a new Supreme Council.

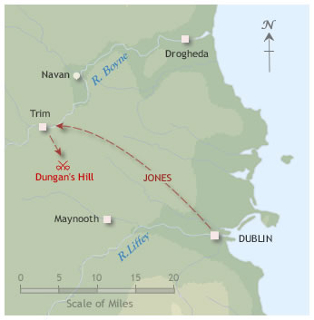

However, the following year, the Confederates’ attempts to drive the remaining English (mainly Parliamentarian) armies from Ireland meets with disaster at the battles of Dungan’s Hill on August 8, 1647 and Knocknanuss on November 13, 1647. As a result, the chastened Confederates hastily conclude a new deal with the English Royalists to try to prevent a Parliamentarian conquest of Ireland in 1648. Although the terms of this second deal are better than those of the first one, Rinuccini again tries to overturn the treaty. However, on this occasion, the Catholic clergy are split on whether to accept the deal, as are the Confederate military commanders and the General Assembly. Ultimately, the treaty is accepted by the Confederacy, which then dissolves itself and joins a Royalist coalition. Rinuccini backs Owen Roe O’Neill, who used his Ulster army to fight against his former comrades who had accepted the deal. He tries in vain to repeat his success of 1646 by excommunicating those who support the peace. However, the Irish bishops are split on the issue and so his authority is diluted. Militarily, Owen Roe O’Neill is unable to reverse the political balance.

Despairing of the Catholic cause in Ireland, Rinnuccini leaves the country on February 23, 1649, embarking at Galway on the ship that had brought him to Ireland, the frigate San Pietro. In the same year, Oliver Cromwell leads a Parliamentarian re-conquest of the country, after which Catholicism is thoroughly repressed. Roman Catholic worship is banned, Irish Catholic-owned land is widely confiscated east of the River Shannon, and captured Catholic clergy are executed.

Rinuccini returns to Rome, where he writes an extensive account of his time in Ireland, the Commentarius Rinuccinanus. His account blames personal vainglory and tribal divisions for the Catholic disunity in Ireland. In particular, he blames the Old English for the eventual Catholic defeat. The Gaelic Irish, he writes, despite being less civilised, are more sincere Catholics.

Rinuccini returns to his diocese in Fermo in June 1650 and dies there on December 13, 1653.