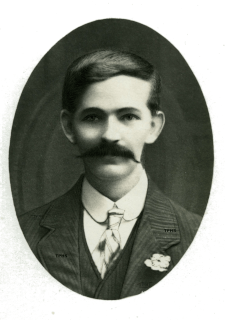

Kevin Gerard Barry, Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteer and medical student, is born on January 20, 1902, at 8 Fleet Street, Dublin. He becomes the first Irish republican to be executed by the British Government since the leaders of the Easter Rising.

Barry is the fourth of seven children born to Thomas Barry, dairyman, and Mary Barry (née Dowling), both originally from northeast County Carlow. His father dies of heart disease on February 8, 1908, at the age of 56. His mother then moves the family to the family’s farm at Tombeagh, Hacketstown, County Carlow, while retaining the family’s townhouse on Fleet Street. As a child he goes to the National School in Rathvilly. In 1915, he is sent to live in Dublin and attends the O’Connell Schools for three months, before enrolling in the Preparatory Grade at St. Mary’s College, Rathmines, in September 1915. He remains at that school until May 31, 1916, when it is closed by its clerical sponsors. With the closure of St. Mary’s College, he transfers to Belvedere College, a Jesuit school in Dublin. He joins the Irish Volunteers, the forerunner of the IRA, while still at Belvedere College, and enters University College Dublin (UCD) in 1919 to study medicine.

As a member of 1st Battalion, Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers, he takes part in a successful raid for arms on the military post in King’s Inns, Dublin, on June 1, 1920. Within only six minutes the raiders secure rifles, light machine guns, and large quantities of ammunition, and depart the site with no casualties. He also takes part in an abortive attempt to burn Aughavanagh House, Aughrim, County Wicklow in July 1920, and an attack on a British ration party in Church Street, Dublin, on September 20, with the aim of seizing arms. The final operation fails. Gunfire breaks out, three soldiers of around Barry’s own age are killed or fatally wounded, and he becomes the first Volunteer to be captured in an armed attack since 1916.

During interrogation, Barry is threatened with a bayonet and is mistreated. A general court-martial on October 20, which he refuses to recognise, condemns him to death for murdering the three soldiers, although one of the bullets taken from Private Marshall Whitehead’s body is a .45 calibre, while all witnesses state that Barry was armed with a .38 Mauser Parabellum. Despite widespread appeals on grounds of both clemency and expediency, the cabinet in London and officials in Dublin decide separately against a reprieve, probably because of its likely effect on the morale of soldiers and police.

On October 28, the Irish Bulletin, the official propaganda newspaper produced by Dáil Éireann‘s Department of Publicity, publishes Barry’s statement alleging torture. The headline reads English Military Government Torture a Prisoner of War and are about to Hang him. The Irish Bulletin declares Barry to be a prisoner of war, suggesting a conflict of principles is at the heart of the conflict. The British do not recognise a war and treat all killings by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as murder. The public learns on this day that the date of execution has been fixed for November 1.

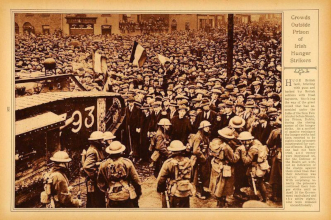

He was hanged in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, on November 1, after hearing two Masses in his cell. The timing of the execution, only seven days after the death by hunger strike of Terence MacSwiney, the republican Lord Mayor of Cork, brings public opinion to a fever-pitch. He is buried in unconsecrated ground on the jail property. His comrade and fellow student Frank Flood is buried alongside him four months later. A plain cross marks their graves and those of Patrick Moran, Thomas Whelan, Thomas Traynor, Patrick Doyle, Thomas Bryan, Bernard Ryan, Edmond Foley and Patrick Maher who are hanged in the same prison before the Anglo-Irish Treaty of July 1921 which ends hostilities between Irish republicans and the British. The graves go unidentified until 1934. They become known as the Forgotten Ten by republicans campaigning for the bodies to be reburied with honour and proper rites. On October 14, 2001, the remains of the ten men are given a state funeral and moved from Mountjoy Prison to be re-interred at Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

Barry is the first person to be tried and executed for a capital offence under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act 1920, passed twelve weeks earlier. Together with his youth, this makes him a republican martyr celebrated in many ballads and verses. The best-known, set to a tune popular with British servicemen, is recorded by the American singer Paul Robeson, among others. A memorial stained-glass window by Richard King of the Harry Clarke Studio is later installed in the former UCD council chamber (afterward called the Kevin Barry Room), Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin.