John Dillon announces the “Plan of Campaign” for Irish tenants against unfair rents on October 17, 1886.

The Plan of Campaign is a stratagem adopted in Ireland between 1886 and 1891, co-ordinated by Irish politicians for the benefit of tenant farmers, against mainly absentee and rack-rent landlords and the tyrannical regime of enforced massive rents and evictions. It is launched to counter agricultural distress caused by the continual depression in prices of dairy products and cattle from the mid-1870s, which leaves many tenants in arrears with rent. Bad weather in 1885 and 1886 also cause crop failure, making it harder to pay rents. The Land War of the early 1880s is about to be renewed after evictions increase and outrages become widespread.

The Plan, conceived by Timothy Healy, is devised and organised by Timothy Harrington, secretary of the Irish National League, William O’Brien and John Dillon. It is outlined in an article headed Plan of Campaign by Harrington which is published on October 23, 1886, in the League’s newspaper, the United Ireland, of which O’Brien is editor.

Dillon is among those who organise a campaign whereby tenants pay their rents to the Land League instead of their landlords. If the tenants are evicted, they are to receive financial assistance from a general fund established for that purpose. As a result of his involvement in this campaign, Dillon spends a number of months in jail.

The measures are to be put into operation on 203 estates, mainly in the south and west of the country though including some scattered Ulster estates. Initially sixty landlords accept the reduced rents, twenty-four holding out but then agreeing to the tenant conditions. Tenants give in on fifteen estates. The chief trouble occurs on the remaining large estates.

The organisers of the Plan decide to test a number of their measures, expecting the remainder will then give in. Widespread attention is focused on it being implemented by Dillon and O’Brien on the estate of Hubert de Burgh-Canning, 2nd Marquess of Clanricarde, at Portumna, County Galway, on November 19, 1886, where the landlord is an absentee ascendancy landlord. The estate comprising 52,000 acres, or 21,000 hectare, yields 25,000 sterling annually in rents paid by 1,900 tenants. The hard-pressed tenants look for a reduction of twenty-five percent. The landlord refuses to give any abatement. The tenant’s reduced rents are then placed into an estate fund, and the landlord informed he will only receive the monies when he agrees to the reduction. Tenants on other estates then follow the example of the Clanricarde tenants, the Plan on each estate led by a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) Campaign activists including Pat O’Brien, Alexander Blane or members of its constituency organisation, the National League. Some 20,000 tenants are involved.

In 1887, a rent strike takes place on the estate of Lady Kingston near Mitchelstown, County Cork. Another of the Land Leaguers, William O’Brien, is brought to court on charges of inciting non-payment of rent. Dillon organises an 8,000 strong crowd to demonstrate outside the courthouse. Three estate tenants are shot by police and others are injured. This incident becomes known as the “Mitchelstown Massacre.”

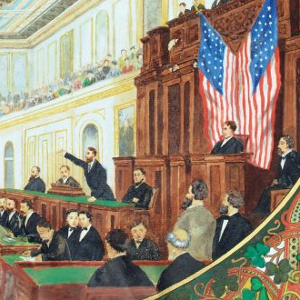

In December 1890, following the verdict in the O’Shea v O’Shea and Parnell divorce case, the IPP splits. This diverts attention from the Campaign which slowly peters out. The IPP also wants to disassociate itself from the more violent aspects on the approach to the Second Home Rule Bill that narrowly succeeds with a majority of 30 in the House of Commons but is then defeated by the House of Lords in 1893.

The Irish land question is addressed after the 1902 Land Conference by the main reforming Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903, during Arthur Balfour‘s short tenure as Prime Minister in 1902–05, allowing Irish tenant farmers to buy the freehold title to their land with low annuities and affordable government-backed loans.

(Pictured: Eviction scene, Woodford Galway 1888, during the Plan of Campaign. The Woodford evictions become some of the most highly resisted with numerous pamphlets, during the period, referring to them)