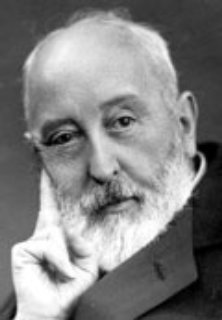

Timothy Michael “Tim” Healy, Irish nationalist politician, journalist, author, barrister, and one of the most controversial Irish Members of Parliament (MPs) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, is born in Bantry, County Cork on May 17, 1855.

Healy is the second son of Maurice Healy, clerk of the Bantry Poor Law Union, and Eliza Healy (née Sullivan). His elder brother, Thomas Healy (1854–1924), is a solicitor and Member of Parliament (MP) for North Wexford and his younger brother, Maurice Healy (1859–1923), with whom he holds a lifelong close relationship, is a solicitor and MP for Cork City.

Healy’s father is transferred in 1862 to a similar position in Lismore, County Waterford. He is educated at the Christian Brothers school in Fermoy, and is otherwise largely self-educated, in 1869, at the age of fourteen, he goes to live with his uncle Timothy Daniel Sullivan in Dublin.

Healy then moves to England in 1871, working first as a railway clerk and then from 1878 in London as parliamentary correspondent of The Nation, writing numerous articles in support of Charles Stewart Parnell, the newly emergent and more militant home rule leader, and his policy of parliamentary obstructionism. Healy takes part in Irish politics and becomes associated with Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party. After being arrested for intimidation in connection with the Irish National Land League, he is promptly elected as member of Parliament for Wexford Borough in 1880.

In Parliament, Healy becomes an authority on the Irish land question. The “Healy Clause” of the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881, which protects tenant farmers’ agrarian improvements from rent increases imposed by landlords, not only makes him popular throughout nationalist Ireland but also wins his cause seats in Protestant Ulster. He breaks with Parnell in 1886 and generally remains at odds with subsequent leaders of the Irish Parliamentary Party, though he is a strong supporter of proposals for Irish Home Rule. Meanwhile, he is called to the Irish bar in 1884 and becomes a queen’s counsel in 1899.

Dissatisfied with both the Liberals and the Irish Nationalists after the Easter Rising in 1916, Healy supports Sinn Féin after 1917. He returns to considerable prominence in 1922 when, on the urging of the soon-to-be Irish Free State‘s Provisional Government of W.T. Cosgrave, the British government recommends to King George V that Healy be appointed the first “Governor-General of the Irish Free State,” a new office of representative of the Crown created in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and introduced by a combination of the Irish Free State Constitution and Letters Patent from the King.

Healy believes that he has been awarded the Governor-Generalship for life. However, the Executive Council of the Irish Free State decides in 1927 that the term of office of Governors-General will be five years. As a result, he retires from the office and public life in January 1928 and publishes his extensive two volume memoirs later in that year. Throughout his life he is formidable because he is ferociously quick-witted, because he is unworried by social or political convention, and because he knows no party discipline. Towards the end of his life, he becomes more mellowed and otherwise more diplomatic.

Healy dies on March 26, 1931, at the age of 75, in Chapelizod, County Dublin. He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.