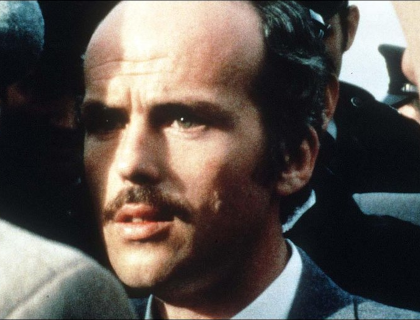

Francis Joseph Sean Hughes, a volunteer in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and an Irish political prisoner, dies on hunger strike in Long Kesh Detention Centre on May 12, 1981. He is the most wanted man in Northern Ireland until his arrest following a shoot-out with the British Army in which a British soldier is killed. At his trial, he is sentenced to a total of 83 years’ imprisonment.

Hughes is born in Bellaghy, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, on February 28, 1956, into a republican family, the youngest of four brothers in a family of ten siblings. His father, Joseph, had been a member of the Irish Republican Army in the 1920s and one of his uncles had smuggled arms for the republican movement. This results in the Hughes family being targeted when internment is introduced in 1971, and his brother Oliver is interned for eight months without trial in Operation Demetrius. He leaves school at the age of 16 and starts work as an apprentice painter and decorator.

Hughes is returning from an evening out in Ardboe, County Tyrone, when he is stopped at an Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) checkpoint. When the soldiers realise he comes from a republican family, he is badly beaten. His father encourages him to see a doctor and report the incident to the police, but he refuses, saying he “would get his own back on the people who did it, and their friends.”

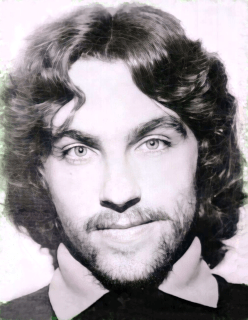

Hughes initially joins the Official Irish Republican Army but leaves after the organisation declares a ceasefire in May 1972. He then joins up with Dominic McGlinchey, his cousin Thomas McElwee and Ian Milne, before the three decide to join the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1973. He, Milne and McGlinchey take part in scores of IRA operations, including daylight attacks on Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) stations, bombings, and attacks on off-duty members of the RUC and UDR. Another IRA member describes the activities of Hughes:

“He led a life perpetually on the move, often moving on foot up to 20 miles for one night then sleeping during the day, either in fields and ditches or safe houses; a soldierly sight in his black beret and combat uniform and openly carrying a rifle, a handgun and several grenades as well as food rations.”

On April 18, 1977, Hughes, McGlinchey and Milne are travelling in a car near the town of Moneymore when an RUC patrol car carrying four officers signals them to stop. The IRA members attempt to escape by performing a U-turn but lose control of the car which ends up in a ditch. They abandon the car and open fire on the RUC patrol car, killing two officers and wounding another, before running off through the fields. A second RUC patrol comes under fire while attempting to prevent the men from fleeing, and despite a search operation by the RUC and British Army the IRA members escape. Following the Moneymore shootings, the RUC name Hughes as the most wanted man in Northern Ireland, and issue wanted posters with pictures of Hughes, Milne and McGlinchey. Milne is arrested in Lurgan, County Armagh, in August 1977, and McGlinchey later in the year in the Republic of Ireland.

Hughes is arrested on March 17, 1978, at Lisnamuck, near Maghera in County Londonderry, after an exchange of gunfire with the British Army the night before. British soldiers manning a covert observation post spot Hughes and another IRA volunteer approaching them wearing combat clothing with “Ireland” sewn on their jackets. Thinking they might be from the Ulster Defence Regiment, one of the soldiers stands up and calls to them. The IRA volunteers open fire on the British troops, who return fire. A soldier of the Special Air Service (SAS), Lance Corporal David Jones, is killed and another soldier wounded. Hughes is also wounded and is arrested nearby the next morning.

In February 1980, Hughes is sentenced to a total of 83 years in prison. He is tried for, and found guilty of, the murder of one British Army soldier (for which he receives a life sentence) and wounding of another (for which he receives 14 years) in the incident which leads to his arrest, as well as a series of gun and bomb attacks over a six-year period. Security sources describe him as “an absolute fanatic” and “a ruthless killer.” Fellow republicans describe him as “fearless and active.”

Hughes is involved in the mass hunger strike in 1980 and is the second prisoner to join the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike in the H-Blocks at the Long Kesh Detention Centre. His hunger strike begins on March 15, 1981, two weeks after Bobby Sands began his hunger strike. He is also the second striker to die, at 5:43 p.m. BST on May 12, after 59 days without food, refusing requests from the IRA leadership outside the prison to end the strike after the death of Sands. The journey of his body from the prison to the well-attended funeral near Bellaghy is marked by rioting as the hearse passes through loyalist areas. His death leads to an upsurge in rioting in nationalist areas of Northern Ireland.

Hughes’s cousin Thomas McElwee is the ninth hunger striker to die. Oliver Hughes, one of his brothers, is elected twice to Magherafelt District Council.

Hughes is commemorated on the Irish Martyrs Memorial at Waverley Cemetery in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and is portrayed by Fergal McElherron in the film H3.