Frances Browne, Irish poet and novelist, best remembered for Granny’s Wonderful Chair, her collection of short stories for children, is born on January 16, 1816, at Stranorlar, County Donegal, the seventh child in a family of twelve children.

Browne is blind from infancy as a consequence of an attack of smallpox when she is only 18 months old. In her writings, she recounts how she learned by heart the lessons which her brothers and sisters said aloud every evening, and how she bribed them to read to her by doing their chores. She then worked hard at memorising all that she had heard. She writes her first poem, a version of “The Lord’s Prayer,” when she is seven years old.

In 1841, her first poems are published in the Irish Penny Journal and in the London Athenauem. One of those included in the Irish Penny Journal is the beautiful lyric “Songs of Our Land” which can be found in many anthologies of Irish patriotic verse. She publishes a complete volume of poems in 1844, and a second volume in 1847. The provincial newspapers, especially the Belfast-based Northern Whig reprint many of her poems and she becomes widely known as “The Blind Poetess of Ulster.”

In 1845 she makes her first contribution to the popular magazine Chambers’s Journal and she writes for this journal for the next 25 years. The first short story that she has published in the Journal is entitled, “The Lost New Year’s Gift,” appearing in March 1845. She also contributes many short stories to magazines that have a largely female readership.

In 1847, she leaves Donegal for Edinburgh with one of her sisters as her reader and amanuensis. She quickly establishes herself in literary circles, and writes essays, reviews, stories, and poems, in spite of health problems. In 1852, she moves to London, where she writes her first novel, My Share of the World (1861). Her best-known work, Granny’s Wonderful Chair, is published in 1856. It remains in print to this day and has been translated into several languages. It is a richly imaginative collection of fairy stories. It is also in 1856 that Pictures and Songs of Home appears, her third volume of poetry. This is directed at very young children and contains beautiful illustrations. The poems focus on her childhood experiences in County Donegal and provide evocative of its countryside.

After her move to London she writes for the Religious Tract Society, making many contributions to their periodicals The Leisure Hour and The Sunday at Home. One of these is “1776: a tale of the American War of Independence” which is printed in The Leisure Hour on the centenary of that event in 1876. As well as describing some of the revolutionary events, it is also a touching love story and is beautifully illustrated. Her last piece of writing is a poem called “The Children’s Day” which appears in The Sunday at Home in 1879.

Frances Brown dies from apoplexy on August 21, 1879, at 19 St. John’s Grove in Richmond-upon-Thames. She is buried on August 25, 1879, in plot 40 in the cemetery at St. Mary Magdalene Church in Richmond, London. Frances dies unmarried and leaves all her belongings, valued at less than 100 pounds, to Eliza Hickman who had been her faithful companion and secretary for many years.

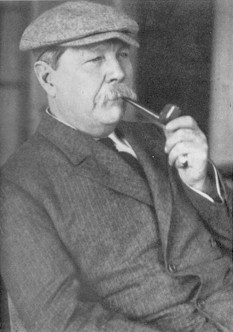

(Pictured: Frances Brown from the family photo collection of Selwyn Glynn, Brisbane, Australia)