Terence Albert O’Brien (Irish: Muiris Ó Briain Aradh), Irish priest of the Dominican Order and Roman Catholic Bishop of Emly, dies on October 30, 1651.

O’Brien is born into the Gaelic nobility of Ireland at Cappamore, County Limerick in 1601. Both of his parents are from the derbhfine of the last Chief of the Name of Clan O’Brien Arradh and claim lineal descent from Brian Boru. His family owns an estate of 2,500 Irish acres centered around Tuogh, which is later confiscated by the Commonwealth of England. He joins the Dominicans in 1621 at Limerick, where his uncle, Maurice O’Brien, is then prior. He takes the name “Albert” after the Dominican scholar Albertus Magnus. In 1622, he goes to study in Toledo, Spain, returning eight years later to become prior at St. Saviour’s in Limerick. In 1643, he is provincial of the Dominicans in Ireland. In 1647, he is consecrated Bishop of Emly by Giovanni Battista Rinuccini.

During the Irish Confederate Wars, like most Irish Catholics, O’Brien sides with Confederate Ireland. His services to the Catholic Confederation are highly valued by the Supreme Council. He treats the wounded and supports Confederate soldiers throughout the conflict. He is against a peace treaty that does not guarantee Catholic freedom of worship in Ireland and in 1648 signs the declaration against the Confederate’s truce with Murrough O’Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin, who has committed atrocities such as the Sack of Cashel against Catholic clergy and civilians, and the declaration against the Protestant royalist leader, James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormond, in 1650 who, due to his failure to resist the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland is not deemed fit to command Catholic troops. He is one of the prelates, who, in August 1650 offers the Protectorate of Ireland to Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine.

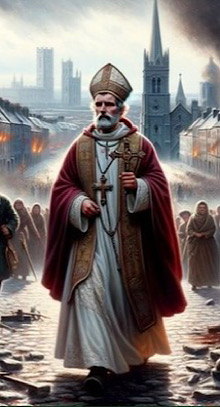

In 1651, Limerick is besieged and O’Brien urges a resistance that infuriates the Ormondists and Parliamentarians. Following surrender, he is found ministering to the wounded and ill inside a temporary plague hospital. As previously decided by the besieging army, O’Brien is denied quarter and protection. Along with Alderman Thomas Stritch and English Royalist officer Colonel Fennell, he is tried by a drumhead court-martial and sentenced to death by New Model Army General Henry Ireton. On October 30, 1651, O’Brien is first hanged at Gallows Green and then posthumously beheaded. His severed head is afterward displayed spiked upon the river gate of the city.

After the successful fight that is eventually spearheaded by Daniel O’Connell for Catholic emancipation between 1780 and 1829, interest revives as the Catholic Church in Ireland is rebuilding after three hundred years of being strictly illegal and underground. As a result, a series of re-publications of primary sources relating to the period of the persecutions and meticulous comparisons against archival Government documents in London and Dublin from the same period are made by Daniel F. Moran and other historians.

The first Apostolic Process under Canon Law begins in Dublin in 1904, after which a positio is submitted to the Holy See.

In the February 12, 1915 Apostolic decree, In Hibernia, heroum nutrice, Pope Benedict XV formally authorizes the formal introduction of additional Causes for Roman Catholic Sainthood.

During a further Apostolic Process held in Dublin between 1917 and 1930 and against the backdrop of the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War, the evidence surrounding 260 alleged cases of Roman Catholic martyrdom are further investigated, after which the findings are again submitted to the Holy See.

On September 27, 1992, O’Brien and sixteen other Irish Catholic Martyrs are beatified by Pope John Paul II. June 20th, the anniversary of the 1584 execution of Elizabethan era martyr Dermot O’Hurley, is assigned as the feast day of all seventeen. A large backlighted portrait of him is on display in St. Michael’s Church, Cappamore, County Limerick, which depicts him during The Siege of Limerick.