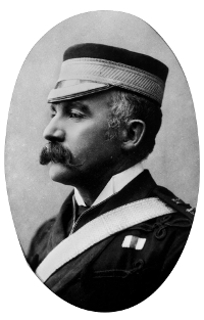

Captain George Edward Henry McElroy MC & Two Bars, DFC & Bar, a leading Irish fighter pilot of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force during World War I, is killed by ground fire on July 31, 1918, while flying over enemy lines. He is credited with 47 aerial victories.

McElroy is born on May 14, 1893 at Donnybrook, County Dublin, to Samuel and Ellen McElroy. He enlists promptly at the start of World War I in August 1914, and is shipped out to France two months later. He is serving as a corporal in the Motor Cyclist Section of the Royal Engineers when he is first commissioned as a second lieutenant on May 9, 1915. While serving in the Royal Irish Regiment he is severely affected by mustard gas and is sent home to recuperate. He is in Dublin in April 1916, during the Easter Rising, and is ordered to help quell the insurrection. He refuses to fire upon his fellow Irishmen, and is transferred to a southerly garrison away from home.

On June 1, 1916 McElroy relinquishes his commission in the Royal Irish Regiment when awarded a cadetship at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, from which he graduates on February 28, 1917, and is commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery.

McElroy is promptly seconded to the Royal Flying Corps, being trained as a pilot at the Central Flying School at Upavon Aerodrome, and appointed a flying officer on June 28. On July 27 his commission is backdated to February 9, 1916, and he is promoted to lieutenant on August 9. On August 15 he joins No. 40 Squadron RFC, where he benefits from mentoring by Edward “Mick” Mannock. He originally flies a Nieuport 17, but with no success in battle. By the year’s end he is flying Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5s and claims his first victory on December 28.

An extremely aggressive dog-fighter who ignores often overwhelming odds, McElroy’s score soon grows rapidly. He shoots down two German aircraft in January 1918, and by February 18 has run his string up to 11. At this point, he is appointed a flight commander with the temporary rank of captain, and transferred to No. 24 Squadron RFC. He continues to steadily accrue victories by ones and twos. By March 26, when he is awarded the Military Cross, he is up to 18 “kills.” On April 1, the Army’s Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) are merged to form the Royal Air Force, and his squadron becomes No. 24 Squadron RAF. He is injured in a landing accident on April 7 when he brushes a treetop while landing. By then he has run his score to 27. While he is sidelined with his injury, on April 22, he is awarded a bar to his Military Cross. Following his convalescence, he returns to No. 40 Squadron in June, scoring three times, on June 26, June 28, and June 30. The latter two triumphs are observation balloons and run his tally to 30.

In July, McElroy adds to his score almost daily, a third balloon busting on July 1, followed by one of the most triumphant months in the history of fighter aviation, adding 17 victims during the month. His run of success is threatened on July 20 by a vibrating engine that entails breaking off an attack on a German two seater and a rough emergency landing that leaves him with scratches and bruises. There is a farewell luncheon that day for his friend Gwilym Hugh “Noisy” Lewis. Their mutual friend “Mick” Mannock pulls McElroy aside to warn him about the hazards of following a German victim down within range of ground fire.

On July 26, “Mick” Mannock is killed by ground fire. Ironically, on that same day, “McIrish” McElroy receives the second Bar to his Military Cross. He is one of only ten airmen to receive the second Bar.

McElroy’s continues apparent disregard for his own safety when flying and fighting can have only one end. On July 31, 1918, he reports destroying a Hannover C for his 47th victory. He then sets out again. He fails to return from this flight and is posted missing. Later it is learned that he had been killed by ground fire. He is 25 years old.

McElroy receives the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously on August 3, citing his shooting down 35 aeroplanes and three observation balloons. The Bar would arrive still later, on September 21, and would laud his low-level attacks. In summary, he shoots down four enemy aircraft in flames and destroys 23 others, one of which he shares destroyed with other pilots. He drives down 16 enemy aircraft “out of control” and out of the fight. In one of those cases, it is a shared success. He also destroys three balloons.

McElroy is interred in Plot I.C.1 at the Laventie Military Cemetery in La Gorgue, northern France.

Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant-Colonel