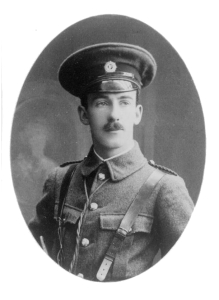

Michael Joseph O’Rahilly, Irish republican and nationalist known as The O’Rahilly, is born in Ballylongford, County Kerry, on April 22, 1875.

O’Rahilly is educated in Clongowes Wood College. As an adult, he becomes a republican and a language enthusiast. He joins the Gaelic League and becomes a member of An Coiste Gnotha, its governing body. He is well travelled, spending at least a decade in the United States and in Europe before settling in Dublin.

O’Rahilly is a founding member of the Irish Volunteers in 1913, which is organized to work for Irish independence and resist the proposed Home Rule. He serves as the IV Director of Arms. He personally directs the first major arming of the Irish Volunteers, the landing of 900 Mausers at the Howth gun-running on July 26, 1914.

O’Rahilly is not party to the plans for the Easter Rising, nor is he a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), but he is one of the main people who train the Irish Volunteers for the coming fight. The planners of the Rising go to great lengths to prevent those leaders of the Volunteers who are opposed to unprovoked, unilateral action from learning that a rising is imminent, including its Chief-of-Staff Eoin MacNeill, Bulmer Hobson, and O’Rahilly. When Hobson discovers that an insurrection is planned, he is kidnapped by the Military Council leadership.

Learning this, O’Rahilly goes to Patrick Pearse‘s school, Scoil Éanna, on Good Friday. He barges into Pearse’s study, brandishing his revolver as he announces, “Whoever kidnaps me will have to be a quicker shot!” Pearse calms O’Rahilly, assuring him that Hobson is unharmed, and will be released after the rising begins.

O’Rahilly takes instructions from MacNeill and spends the night driving throughout the country, informing Volunteer leaders in Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, and Limerick that they are not to mobilise their forces for planned manoeuvres on Sunday.

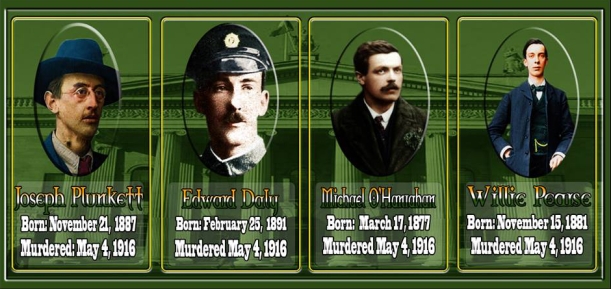

Arriving home, O’Rahilly learns that the Rising is about to begin in Dublin on the next day, Easter Monday, April 24, 1916. Despite his efforts to prevent such action which he feels can only lead to defeat, he sets out to Liberty Hall to join Pearse, James Connolly, Thomas MacDonagh, Tom Clarke, Joseph Plunkett, Countess Markievicz, Seán Mac Diarmada, Eamonn Ceannt and their Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army troops. Arriving in his De Dion-Bouton motorcar, he gives one of the most quoted lines of the rising, “Well, I’ve helped to wind up the clock — I might as well hear it strike!”

O’Rahilly fights with the General Post Office (GPO) garrison during Easter Week. On Friday, April 28, with the GPO on fire, O’Rahilly volunteers to lead a party of men along a route to Williams and Woods, a factory on Great Britain Street, now Parnell Street. A British machine-gun at the intersection of Great Britain and Moore streets cuts him and several of the others down. Wounded and bleeding badly, O’Rahilly slumps into a doorway on Moore Street, but hearing the English marking his position, makes a dash across the road to find shelter in Sackville Lane, now O’Rahilly Parade. He is wounded diagonally from shoulder to hip by sustained fire from the machine-gunner.

The specific timing of O’Rahilly’s death is very difficult to pin down but understanding can be gained from his final thoughts. Despite his obvious pain, he takes the time to write a message to his wife on the back of a letter he received from his son in the GPO. It is this last message to Nancy that artist Shane Cullen etches into his limestone and bronze sculpture. The text reads:

Written after I was shot. Darling Nancy I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street and took refuge in a doorway. While I was there, I heard the men pointing out where I was and made a bolt for the laneway I am in now. I got more [than] one bullet, I think. Tons and tons of love dearie to you and the boys and to Nell and Anna. It was a good fight anyhow. Please deliver this to Nannie O’ Rahilly, 40 Herbert Park, Dublin. Goodbye Darling.