David Andrew (Davy) Hammond, singer, folklorist, television producer and documentary maker, is born on December 5, 1928, in Miss Kell’s nursing home on the Castlereagh Road in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Hammond is the son of Leslie Hammond, a tram driver, and his wife Annie (née Lamont). His parents are not city people; his mother grew up near Ballybogy in the Ballymoney area of County Antrim, and his father, though from a family with roots in south County Londonderry, had lived in Ballymoney as a boy, and had been apprenticed to a blacksmith there. Both have a strong sense of their rural identity and maintain the Ulster Scots dialect of their childhood. They are never quite at home in the Belfast suburb of Cregagh, and in particular do not share the sectarian attitudes that are much more present in 1930s Belfast than they had been in north Antrim, one of the last strongholds of Presbyterian radicalism. Even as a boy, Hammond is interested in the old songs that his mother sang and realises that the traditions in which his parents had been nurtured are disappearing quickly in an increasingly urbanising and modernising world. When he encounters the work of Emyr Estyn Evans in the early 1940s, he is encouraged to document both rural tradition and the street life of the city, and he and a couple of friends, though still just teenagers, ride off on their bicycles to look for folklore in the hinterland of Belfast.

After primary school, Hammond wins a scholarship in 1941 to Methodist College Belfast, where he does well in examinations, and then goes to Stranmillis University College to train as a teacher. In his first job, in Harding Memorial primary school in east Belfast, he proves to be a popular, idealistic teacher, and is remembered by his pupils fifty years later as a fine singer and a teller of ghost stories, who had taken the class on memorable youth-hosteling trips to the Mourne Mountains. Youth hosteling and folklore collecting increases his awareness and understanding of the rich traditions of the whole community in the north of Ireland, and he is never constrained by political or religious barriers. His early career mirrors closely that of James Hawthorne, and their paths are to cross in later life.

Hammond is friendly with many others active in the cultural life of Northern Ireland and makes a name for himself as a song collector and eventually as an expert on all aspects of traditional singing. In 1956, he is awarded a scholarship to travel in the United States to meet the important pioneers of folk-music collecting and performance there. He records his first LP record of Ulster songs, I Am The Wee Falorie Man (1958), in the United States, and becomes friends with Pete Seeger, the Appalachian singer Jean Ritchie, with old blues singers, and notably with Liam Clancy, one of the three Clancy brothers who as a quartet with Tommy Makem are to popularise Irish folk music in the United States and elsewhere.

On returning to Belfast, Hammond takes a job in 1958 in Orangefield secondary school in the east of the city, where the highly regarded headmaster John Malone encourages new approaches to education. Among his pupils at Orangefield is George Ivan “Van” Morrison, who credits him with inspiring his interest in Irish traditional music. Hammond enjoys teaching but is increasingly drawn to folk-song performance and recording. He appears regularly on radio programmes of the BBC and Radio Éireann, and in 1964 joins the school’s department in BBC Northern Ireland. There, with colleagues like Sam Hanna Bell, James Hawthorne and others, he works on programmes such as Today and Yesterday in Northern Ireland, which for the first time introduces pupils (and many adults) to local history and to aspects of tradition. In 1968, with two friends, the poets Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley, he puts on poetry and traditional music events in schools all over the province. The Arts Council funds the Room to Rhyme project, which is immensely influential and inspiring, and is still talked about many years later by those who attended as children.

Hammond is creatively involved with hundreds of hours of broadcasting, in television as well as radio, and eventually for adults as well as children. He writes scripts, produces documentary series such as Ulster in Focusand Explorations, and brings an artistic sensibility to filming, as well as working sympathetically with traditional singers and craftspeople. Dusty Bluebells, a sensitively made film of Belfast children’s street games, wins the prestigious Golden Harp award in 1972. After he leaves the BBC to work as a freelance, and founds Flying Fox Films in 1986, he continues making documentaries on many aspects of Ulster life and heritage. His film called Steel Chest, Nail in the Boot and the Barking Dog (1986), about working in the Belfast shipyards, also wins a Golden Harp award. A companion book of the same name is published. Another book is Belfast, City of Song(1989), with Maurice Leyden. In 1979, he edits a volume of the songs of Thomas Moore. His documentary programmes include films about singers from Boho, County Fermanagh, and about the big houses of the gentry in Ireland. The Magic Fiddle (1991/2) examines the role of the instrument in the folk music of Ireland, Scandinavia, Canada, and the American south, while Another Kind of Freedom (1993) is about the experiences of a former Orangefield pupil, the Beirut hostage Brian Keenan. He also produces and directs the films Something to Write Home About (1998), Where Are You Now? (1999), and Bogland (1999), all of which explore Seamus Heaney’s home region and experiences.

The first poem in Heaney’s collection Wintering Out (1972) is entitled “For David Hammond and Michael Longley.” Their lifelong friendship leads to several other creative collaborations. In particular, after a distressing evening in 1972 when Hammond, affected by the despair and terror unleashed by Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombing of his city, is for once unable to sing, Heaney meditates on the experience in an essay and in an important poem, “The singer’s house” (subsequently included in his 1979 Field Work collection). The poem urges the singer to keep singing, to defend the values of art and friendship in a hostile time. Hammond collaborates with Dónal Lunny and other traditional musicians to bring out an LP also called The Singer’s House(1978), which includes Heaney’s poem on the album sleeve, and features some of the songs that he had made famous, such as “My Aunt Jane” and “Bonny Woodgreen,” from his vast repertoire of songs from Ulster. The album is reissued in 1980.

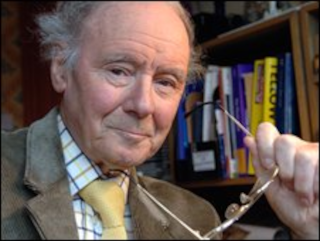

In 1995, Hammond is one of Heaney’s personal guests at the award of his Nobel prize in Stockholm, characteristically wearing his usual, mustard-yellow, cattle-dealer boots with evening dress. On another formal occasion, when he is awarded an honorary doctorate by Dublin City University in November 2003, he surprises the audience by standing up in his academic robes to sing “My Lagan love,” instead of giving an address. His unique, light mellow voice is an ideal vehicle for the traditional ballads which he knows so well. He records a number of records in the 1960s, including Belfast Street Songs, and publishes the book Songs of Belfast (1978). He also encourages traditional musicians like Arty McGlynn, and collaborates with them on various recording projects. He is well known for live and often impromptu performances at festivals and venues in Ireland and the United States. He also performs at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

Hammond is also a notable collaborator with poets and dramatists, especially in the important Field Day Theatre Company project, of which he is a director, along with Seamus Heaney, Tom Paulin, Seamus Deane, Thomas Kilroy, and the project’s founders, Brian Friel and Stephen Rea. He supports the Field Day search for a “fifth province,” where history and community and culture can intersect, believing that to speak unthinkingly of “two traditions” is to perpetuate superficial political divisions. As he says in an interview in The Irish Times on July 4, 1998, songs can “take you out of yourself” and become bridges to unite people.

Hammond receives many honours. In 1994, he receives the Estyn Evans award for his contribution to mutual understanding, and his work is featured in several major events in his honour: in the University of North Florida (1999), in the Celtic Film Festival in Belfast (2003), and in Belfast’s Linen Hall Library (2005). A Time to Dream, a film about his life and work, is broadcast on BBC Northern Ireland in December 2008.

Hammond dies in hospital in Belfast, after a long illness, on August 25, 2008, survived by his wife Eileen (née Hambleton), whom he marries on July 19, 1954, and by their son and three daughters. His funeral in St. Finnian’s Church is a major cultural event, where friends sing, play and speak in his honour.

In Seamus Heaney’s last collection of poetry, Human Chain (2010), he includes a poignant farewell to Hammond. The poet imagines (or perhaps dreams) of another visit to the singer’s house, but this time “The door was open, and the house was dark.”

(From: “Hammond, David Andrew (‘Davy’)” by Linde Lunney, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, December 2014)