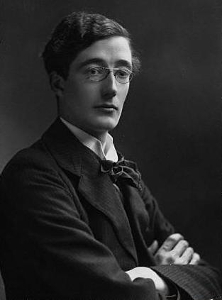

Sir Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis, English actor who holds both British and Irish citizenship, is born in Kensington, London, England, on April 29, 1957.

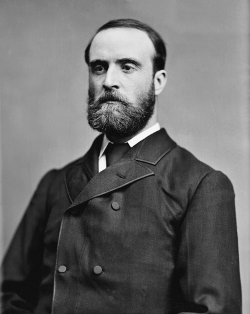

Day-Lewis is the son of poet Cecil Day-Lewis and English actress Jill Balcon. His father, who was born in Ballintubbert, County Laois, was of Protestant Anglo-Irish and English background, lived in England from the age of two, and later became the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom. Day-Lewis’s mother was Jewish, and his maternal great-grandparents’ Jewish families emigrated to England from Latvia and Poland. His maternal grandfather, Sir Michael Balcon, was the head of Ealing Studios.

Growing up in London, he excels on stage at the National Youth Theatre, before being accepted at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which he attends for three years. Despite his traditional actor training at the Bristol Old Vic, he is considered to be a method actor, known for his constant devotion to and research of his roles. He often remains completely in character for the duration of the shooting schedules of his films, even to the point of adversely affecting his health. He is one of the most selective actors in the film industry, having starred in only five films since 1998, with as many as five years between roles. Protective of his private life, he rarely gives interviews and makes very few public appearances.

Day-Lewis shifts between theatre and film for most of the early 1980s, joining the Royal Shakespeare Company and playing Romeo in Romeo and Juliet and Flute in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, before appearing in the 1984 film The Bounty. He stars in My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), his first critically acclaimed role, and gains further public notice with A Room with a View (1985). He then assumes leading man status with The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988).

One of the most acclaimed actors of his generation, Day-Lewis has earned numerous awards, including three Academy Awards for Best Actor for his performances in My Left Foot (1989), There Will Be Blood (2007), and Lincoln (2012), making him the only male actor in history to have three wins in the lead actor category and one of only three male actors to win three Oscars. He is also nominated in this category for In the Name of the Father (1993) and Gangs of New York (2002). He has also won four BAFTA Awards for Best Actor in a Leading Role, three Screen Actors Guild Awards, and two Golden Globe Awards. In November 2012, Time names Day-Lewis the “World’s Greatest Actor.”

In 2008, while receiving the Academy Award for Best Actor for There Will Be Blood from Helen Mirren, who presented the award, Day-Lewis kneels before her and she taps him on each shoulder with the Oscar statuette, to which he quips, “That’s the closest I’ll come to ever getting a knighthood.” In November 2014, Day-Lewis is formally knighted by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge at Buckingham Palace for services to drama.

Day-Lewis and his wife, Rebecca Miller, have lived in Annamoe, County Wicklow since 1997.