At dawn on the morning of November 20, 1917, the 16th (Irish) Division of the British Army assaults an area of the German lines known as “Tunnel Trench,” named for an elaborate tunnel system that runs along it. The attack is meant as a diversion for the main attack, about eight miles to the southeast at Cambrai, France, where six infantry and two cavalry divisions of the British Expeditionary Force, with additional support from fourteen squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps, join the British Tank Corps in a surprise attack on the German lines.

By autumn 1917, three years into World War I, continuous shelling and lack of drainage has transformed the Ypres Salient, on the Western Front, into a waterlogged quagmire. In Ireland, meanwhile, a month earlier, Eamon de Valera becomes president of Sinn Féin and decides to push for an independent Irish republic. Despite the growing political turmoil at home, in France, on firm ground near the town of Cambrai, the British Army’s 16th (Irish) Division again proves to be formidable adversaries for the Germans.

According to the divisional historian, at Cambrai, the “swift and successful operation by 16th Division was a model of attack with a limited objective.” In addition to securing 3,000 yards of trench, 635 prisoners are captured from the German army’s 470th and 471st Regiments and 330 German bodies are counted in the trenches. More importantly, though, the mayhem caused by the diversionary assault contributes greatly to the initial success of the Cambrai offensive, though the offensive eventually sputters, dragging the war into 1918.

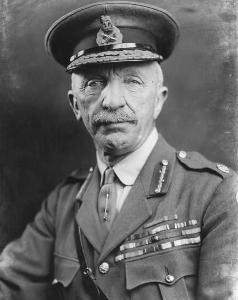

Cambrai becomes the field of operations when the British Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, recognising that it is impossible to launch further military operations in the Ypres sector, seeks a new battlefield where he hopes success can be achieved before year’s end. Lieutenant Colonel John Fuller of the Tank Corps and General Julian Byng, commander of the Third Army, recommend that a massed assault by 400 tanks should be mounted across the firm, chalky ground to the southwest of Cambrai. Haig adopts this proposal, confident that the tanks can punch a hole through the mighty Hindenburg Line and allow his underused Cavalry Divisions to break through to the enemy rear.

In order to create maximum confusion among the Germans, Sir Aylmer Haldane, commander of VI Corps, is ordered to stage a diversionary attack. The area selected for the assault is about eight miles to the northwest of Cambrai, where the British line passes through the villages of Bullecourt and Fontaine-lès-Croisilles. The units select to make this subsidiary attack are 3rd Army and 16th (Irish) Division.

The defences of the Hindenburg Line opposite VI Corps positions consists of Tunnel Trench, a heavily defended front-line trench, with a second, or support trench, some 300 yards behind. The whole area is scattered with concrete machine gun forts, or Mebus, similar to those that had decimated the 16th (Irish) Division at the Battle of Langemarck three months earlier.

Tunnel Trench is so called because it has a tunnel 30 or 40 feet below ground along its entire length, with staircase access from the upper level every 25 yards. The entire tunnel has electric lighting, and side chambers provide storage space for bunks, food, and ammunition. Demolition charges are set that can be triggered from the German rear in order to prevent the defences from falling into British hands.

The 16th (Irish) Division, attacking on a three-brigade front, is assigned the task of capturing a 2,000-yard section of the trench network. On the right flank of the Irishmen, 3rd Division’s 9th Brigade is detailed to capture an additional 800 yards. One unusual feature of the attack is that there is to be no preliminary bombardment as surprise is the key to the success of the operation. Once the assault begins, however, 16th (Irish) Division’s artillery, reinforced with guns from the 34th Division, is to open a creeping barrage upon the German positions.

The morning of the advance, November 20, is overcast, with low visibility. At 6:20 a.m., the Divisional 18 pounder-field guns open fire, and the leading assault companies spring from their jump-off positions. At the same time, Stokes mortars begin to lay a smoke barrage upon the German trenches in imitation of a gas attack. This deception proves successful, as many German troops don cumbersome gas masks and retreat to the underground safety of the tunnel, thus leaving the exposed portion of the trench undefended.

On the left flank, the attack of the 49th Brigade is launched by 2nd Royal Irish Regiment and 7/8th Royal Irish Fusiliers. They quickly cross the 200 yards of no-man’s-land and reach the enemy frontline just as the barrage lifts. Resistance above ground is minimal, and storming parties began the task of flushing the Germans from the tunnel with Mills bombs and bayonets.

Once the tunnel is secure, sappers, acting on information obtained by 7th Leinster Regiment’s intelligence officer, cut the leads connecting the demolition charges. Supporting companies then press on to capture Tunnel Support Trench, while Divisional support units rapidly wire and made secure the new defensive front in anticipation of German counterattacks.

Only on the extreme left flank does 49th Brigade encounter any serious opposition. In this sector, Company “B” of the 7/8th Royal Irish Fusiliers suffers heavy losses inflicted by concentrated machine gun fire from Mebus Flora. Nearly one-hour elapses before resistance from this strong point can be overcome.

In the centre, 10th and 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers head the attack of the 48th Brigade. The advance here is so rapid that the Irish find many Germans still wearing gas masks and unable to fight. Two more Mebus, Juno and Minerva, are stormed and many more prisoners taken, particularly by 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers which captures 170 Germans.

Leading the attack on the right flank is 6th Connaught Rangers and 1st Royal Munster Fusiliers, both of which belong to the 47th “Irish Brigade.”

After capturing their assigned section of Tunnel Trench, two companies of Rangers press forward to assault the strong points known as Mars and Jove. The Division had learned from the disastrous frontal attack made at Langemarck, and so the Rangers work around to the rear before pressing home with the bayonet.

Unfortunately, 3rd Division fails in its attempt to capture the trench network immediately to the right of 16th (Irish) Division, and the flank of the Connaught Rangers is thus exposed to a savage counterattack. The Rangers ferociously engage the Germans and use captured “potato masher” grenades brought up from the tunnel to great effect. Eventually, overwhelming numbers begin to tell, and “A” Company is forced to yield Jove and fall back upon “B” Company, which is holding Mars.

These two isolated companies doggedly hold their ground for several hours. The situation only improves when the Divisional pioneer battalion, the 11th Hampshire Regiment, digs a communication trench across the fire-swept no-man’s-land, thereby allowing the support companies of the Rangers to come to the aid of their comrades. The front is finally stabilised three days later when 7th Leinster Regiment recaptures and consolidates Jove and successfully assaults the untaken section of Tunnel Trench.

On the first day of the Battle of Cambrai, General Byng’s eight attacking Divisions achieve complete surprise and pierce the Hindenburg Line, driving the Germans back four miles toward Cambrai itself. Having captured 8,000 prisoners and 100 guns for the loss of only 5,000 British casualties, it is small wonder that church bells are sounded in celebration in Britain for the first time during the war.

Unfortunately, Byng lacks sufficient reserves to exploit, or consolidate his success, and German counterattacks, launched by some 20 Divisions, recover most of the lost ground. Although the battle ultimately ends in failure for the British, the willingness to employ new weaponry and tactics at Cambrai and during the diversionary assault upon Tunnel Trench, points the way to the final victory in 1918.

Although the capture of Tunnel Trench contributes greatly to the early success at Cambrai, it proves costly as VI Corps suffers 805 casualties. Most of these occur close to Jove Mebus, where the Connaught Rangers had engaged the enemy in hand-to-hand combat.

Perhaps an idea of the ferocious nature of this form of trench warfare can be gleaned from Father William Doyle, chaplain of the 8th Royal Irish Fusiliers, who once remarks, “We should have had more prisoners, only a hot-blooded Irishman is a dangerous customer when he gets behind a bayonet and wants to let daylight through everybody.”

(From: “Tunnel Trench: 16th (Irish) Division Clears the Way at Cambrai,” by Kieron Punch, posted by The Wild Geese, http://www.thewildgeese.irish, January 18, 2013 | Pictured: Troops from the Royal Irish Regiment about to go into action at Cambrai)