The first Dungannon Convention of the Ulster Volunteers on February 15, 1782, calls for an independent Irish parliament. This is the parliament that Henry Grattan also campaigns for and later becomes known as “Grattan’s parliament.”

The Irish Volunteers are a part-time military force whose original purpose is to guard against invasion and to preserve law and order when regular troops are being sent to America during the American Revolutionary War. Members are mainly drawn from the Protestant urban and rural middle classes and the movement soon begins to take on a political importance.

The first corps of Volunteers is formed in Belfast and the movement spreads rapidly across Ireland. By 1782 there are 40,000 enlisted in the Volunteers, half of them in Ulster. Strongly influenced by American ideas, though loyal to the Crown, the Volunteers demand greater legislative freedom for the Dublin Parliament.

The Dungannon Convention is a key moment in the eventual granting of legislative independence to Ireland.

At the time, all proposed Irish legislation has to be submitted to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom for its approval under the great seal of England before being passed by the Parliament of Ireland. English Acts emphasise the complete dependence of the Irish parliament on its English counterpart and English Houses claim and exercise the power to legislate directly for Ireland, even without the agreement of the parliament in Dublin.

The Ulster Volunteers, who assemble in Dungannon, County Tyrone, demand change. Prior to this, the Volunteers received the thanks of the Irish parliament for their stance but in the House of Commons, the British had ‘won over’ a majority of that assembly, which led to a resistance of further concessions. Thus, the 315 volunteers in Ulster at the Dungannon convention promised “to root out corruption and court influence from the legislative body,” and “to deliberate on the present alarming situation of public affairs.”

The Convention is held in a church and is conducted in a very civil manner. The Volunteers agree, almost unanimously, to resolutions declaring the right of Ireland to legislative and judicial independence, as well as free trade. A week later, Grattan, in a great speech, moves an address of the Commons to His Majesty, asserting the same principles but his motion is defeated. So too is another motion by Henry Flood, declaring the legislative independence of the Irish Parliament.

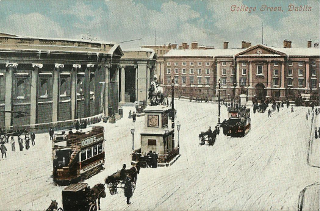

However, the British soon realise they can resist the agitation no longer. It is through ranks of Volunteers drawn up outside the parliament house in Dublin that Grattan passes on April 16, 1782, amidst unparalleled popular enthusiasm, to move a declaration of the independence of the Irish parliament. After a month of negotiations, legislative independence is granted to Ireland.

(Pictured: The original Irish Parliament Building which now houses the Bank of Ireland, College Green, opposite the main entrance to Trinity College, Dublin)