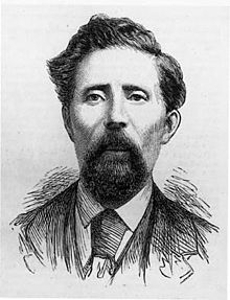

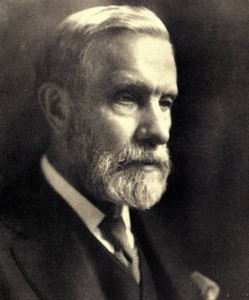

John Devoy, one of the most devoted revolutionaries the world has ever seen, is born in Kill, County Kildare, on September 3, 1842. Dedicating over 60 years of his life to the cause of Irish freedom, he is one of the few people to have played a leading role in the Fenian Rising of 1867, the 1916 Easter Rising, and the Irish War of Independence (1919 – 1921).

After the Great Famine, the family moves to Dublin where Devoy’s father obtains at job at Watkins’ brewery. Devoy attends night school at the Catholic University before joining the Fenians. In 1861 he travels to France with an introduction from Timothy Daniel Sullivan to John Mitchel. Devoy joins the French Foreign Legion and serves in Algeria for a year before returning to Ireland to become a Fenian organiser in Naas, County Kildare.

In 1865, when many Fenians are arrested, James Stephens, founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), appoints Devoy Chief Organiser of Fenians in the British Army in Ireland. His duty is to enlist Irish soldiers in the British Army into the IRB. In November 1865 Devoy orchestrates Stephens’ escape from Richmond Prison in Dublin.

In February 1866 an IRB Council of War calls for an immediate uprising but Stephens refuses, much to Devoy’s annoyance, as he calculated the Fenian force in the British Army to number 80,000. The British get wind of the plan through informers and move the regiments abroad, replacing them with regiments from Britain. Devoy is arrested in February 1866 and interned in Mountjoy Gaol, then tried for treason and sentenced to fifteen years penal servitude. In Portland Prison Devoy organises prison strikes and, as a result, is moved to Millbank Prison in Pimlico, London.

In January 1871, he is released and exiled to the United States as one of the “Cuba Five.” He receives an address of welcome from the House of Representatives. Devoy becomes a journalist for the New York Herald and is active in Clan na Gael. Under Devoy’s leadership, Clan na Gael becomes the central Irish republican organisation in the United States. In 1877 he aligns the organisation with the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland.

In 1875, Devoy and John Boyle O’Reilly organise the escape of six Fenians from Fremantle Prison in Western Australia aboard the ship Catalpa. Devoy returns to Ireland in 1879 to inspect Fenian centres and meets Charles Kickham, John O’Leary, and Michael Davitt en route in Paris. He convinces Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell to co-operate in the “New Departure” during the growing Land War.

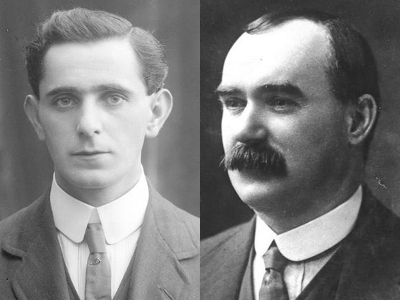

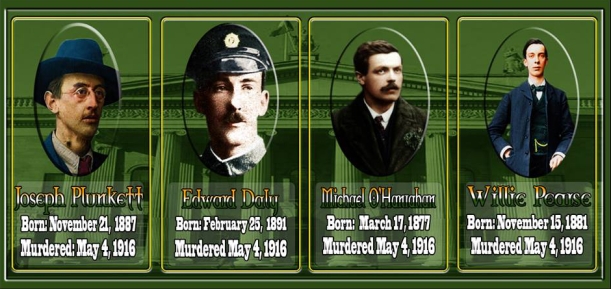

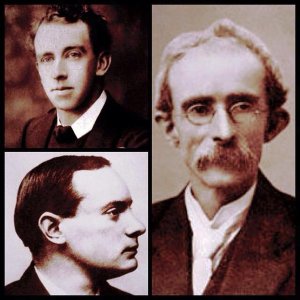

Devoy’s fundraising efforts and work to sway Irish Americans to physical force nationalism makes possible the Easter Rising in 1916. In 1914, Patrick Pearse visits the elderly Devoy in America, and later the same year Roger Casement works with Devoy in raising money for guns to arm the Irish Volunteers. Though he is skeptical of the endeavor, he finances and supports Casement’s expedition to Germany to enlist German aid in the struggle to free Ireland from English rule. Also, before and during World War I, Devoy is also identified closely with the Ghadar Party, and is accepted to have played a major role in supporting Indian Nationalists, as well as playing a key role in the Hindu-German Conspiracy which leads to the trial that is the longest and most expensive trial in the United States at the time.

In 1916 Devoy plays an important role in the formation of the Clan-dominated Friends of Irish Freedom, a propaganda organization whose membership totals 275,000 at one point. The Friends fail in their efforts to defeat Woodrow Wilson for the presidency in 1916. Fearful of accusations of disloyalty for their cooperation with Germans and opposition to the United States’ entering the war on the side of Great Britain, the Friends significantly lower their profile after April 1917. Sinn Féin‘s election victories and the British government’s intentions to conscript in Ireland in April 1917 help to revitalize the Friends.

With the end of the war, Devoy plays a key role in the Friends’ advocacy for not the United States’ recognition of the Irish Republic but, in keeping with President Wilson’s war aims, self-determination for Ireland. The latter does not guarantee recognition of the Republic as declared in 1916 and reaffirmed in popular election in 1918. American Irish republicans challenge the Friends’ refusal to campaign for American recognition of the Irish Republic. Not surprisingly, Devoy and the Friends’ Daniel F. Cohalan become the key players in a trans-Atlantic dispute with de facto Irish president Éamon de Valera, touring the United States in 1919 and 1920 in hopes of gaining U.S. recognition of the Republic and American funds. Believing that the Americans should follow Irish policy, de Valera forms the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic in 1920 with help from the Philadelphia Clan na Gael.

Devoy returns to Ireland and in 1919 addresses Dáil Éireann. He later supports the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. Devoy is editor of The Gaelic American from 1903 until his death in Atlantic City on September 29, 1928. His body is returned to Ireland and buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. A large memorial to him stands on the road between his native Kill and Johnstown.