The U-20, a German U-boat under the command of Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger, sinks the British steamship Centurion off the southeast coast of Ireland on May 6, 1915. This tragic event has far-reaching consequences and shapes the course of World War I.

The Centurion is traveling through the waters southeast of Ireland when a torpedo fired from the U-20 hits the vessel, causing it to rapidly sink. This act of aggression results in the loss of many innocent lives and sends shockwaves throughout the world.

At the time of the incident, World War I is in full swing. Germany, engaged in submarine warfare, seeks to disrupt British supply lines and cut off its access to vital resources. The sinking of merchant ships, regardless of their civilian nature, is part of Germany’s strategy to weaken the enemy. The attack on the Centurion is just one of many instances in which German submarines target and sink British vessels.

A difference in this particular incident as opposed to other similar incidents is the widespread outrage it triggers. The Centurion is an unarmed cargo ship carrying civilian goods, and its destruction is seen as a ruthless and unjustifiable act. The loss of civilian lives and the callousness with which the submarine attack is executed causes public opinion to turn against Germany.

The sinking highlights the growing concern over unrestricted submarine warfare and its impact on civilian populations. It pushes the United States, which at the time is neutral, closer to entering the war on the side of the Allies. The incident also plays a significant role in shaping public opinion in other neutral countries, putting pressure on Germany to reconsider its aggressive tactics.

In response to international outrage, Germany initially defends its actions, arguing that the Centurion was carrying contraband cargo. However, under mounting pressure, the German government eventually backs down and pledges to modify its submarine warfare policies to reduce the risk to civilian lives. This move is meant to appease neutral countries and prevent the United States from entering the war.

The sinking of the Centurion has a lasting impact on maritime warfare. The incident leads to the introduction of new rules of engagement, such as the requirement for submarines to surface and warn civilian vessels before attacking. These rules aim to minimize civilian casualties and reduce the risk of similar tragedies occurring in the future.

Moreover, the sinking serves as a catalyst for technological advancements in submarine warfare. Navies worldwide realize the need for more sophisticated anti-submarine measures and began developing detection systems and tactics to counter the stealth of submarines. This incident marks a turning point in the evolution of naval warfare, as nations seek to adapt and respond to the new challenges posed by underwater vessels.

The following day, May 7, 1915, the U-20 sinks the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania off the southern coast of Ireland. The liner sinks in eighteen minutes with 1,197 casualties. The wreck lies in 300 feet of water.

On November 4, 1916, U-20 becomes grounded on the Danish coast south of Vrist, after suffering damage to its engines. Her crew attempts to destroy her with explosives the following day, succeeding only in damaging the boat’s bow but making it effectively inoperative as a warship.

The U-20 remains on the beach until 1925 when the Danish government blows it up in a “spectacular explosion.” The Danish navy removes the deck gun and makes it unserviceable by cutting holes in vital parts. The gun is kept in the naval stores at Holmen, Copenhagen for almost 80 years. The conning tower is removed and placed on the front lawn of the local museum Strandingsmuseum St. George Thorsminde, where it remains today.

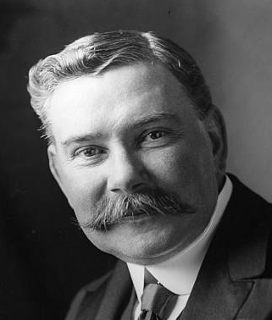

(Pictured: The U-20, second from left, at Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, on February 17, 1914)