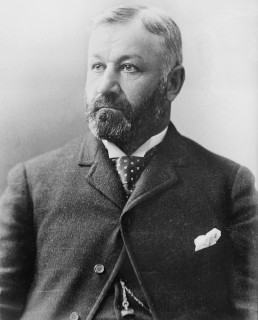

Richard Welstead Croker, American politician who is a leader of New York City‘s Tammany Hall and a political boss also known as “Boss Croker, is born in the townland of Ballyva, in the parish of Ardfield, County Cork on November 24, 1843.

Croker is the son of Eyre Coote Croker (1800–1881) and Frances Laura Welsted (1807–1894). He is taken to the United States by his parents when he is just two years old. There are significant differences between this family and the typical family leaving Ireland at the time. They are Protestant and are not land tenants. Upon arrival in the United States, his father is without a profession, but has a general knowledge of horses and soon becomes a veterinary surgeon. During the American Civil War, he serves in that same capacity under General Daniel Sickles.

Croker is educated in New York public schools but drops out at age twelve or thirteen to become an apprentice machinist in the New York and Harlem Railroad machine shops. Not long after, he becomes a valued member of the Fourth Avenue Tunnel Gang, a street gang that attacks teamsters and other workers that gather around the Harlem line’s freight depot. He eventually becomes the gang’s leader. He joins one of the Volunteer Fire Departments in 1863, becoming an engineer of one of the engine companies. That is his gateway into public life.

James O’Brien, a Tammany associate, takes notice of Croker after he wins a boxing match against Dick Lynch whereby he knocks out all of Lynch’s teeth. He becomes a member of Tammany Hall and active in its politics. In the 1860s he is well known for being a “repeater” at elections, voting multiple times at the polls. He is an alderman from 1868–1870 and Coroner of New York City from 1873–1876. He is charged with the murder of John McKenna, a lieutenant of James O’Brien, who is running for United States Congress against the Tammany-backed Abram S. Hewitt. John Kelly, the new Tammany Hall boss, attends the trial and Croker is freed after the jury is undecided. He moves to Harrison, New York by 1880. He is appointed the New York City Fire Commissioner in 1883 and 1887 and city Chamberlain from 1889-1890.

After the death of Kelly, Croker becomes the leader of Tammany Hall and almost completely controls the organization. As head of Tammany, he receives bribe money from the owners of brothels, saloons and illegal gambling dens. He is chairman of Tammany’s Finance Committee but receives no salary for his position. He also becomes a partner in the real estate firm Meyer and Croker with Peter F. Meyer, from which he makes substantial money, often derived from sales under the control of the city through city judges. Other income comes by way of gifts of stock from street railway and transit companies, for example. At the time, the city police are largely still under the control of Tammany Hall, and payoffs from vice protection operations also contribute to Tammany income.

Croker survives Charles Henry Parkhurst‘s attacks on Tammany Hall’s corruption and becomes a wealthy man. Several committees are established in the 1890s, largely at the behest of Thomas C. Platt and other Republicans, to investigate Tammany and Croker, including the 1890 Fassett Committee, the 1894 Lexow Committee, during which Croker leaves the United States for his European residences for three years, and the Mazet Investigation of 1899.

Croker’s greatest political success is his bringing about the 1897 election of Robert Anderson Van Wyck as first mayor of the five-borough “greater” New York. During Van Wyck’s administration Croker completely dominates the government of the city.

In 1899, Croker has a disagreement with Jay Gould‘s son, George Jay Gould, president of the Manhattan Elevated Railroad Company, when Gould refuses his attempt to attach compressed-air pipes to the Elevated company’s structures. He owns many shares of the New York Auto-Truck Company, a company which would benefit from the arrangement. In response to the refusal, he uses Tammany influence to create new city laws requiring drip pans under structures in Manhattan at every street crossing and the requirement that the railroad run trains every five minutes with a $100 fine for every violation. He also holds 2,500 shares of the American Ice Company, worth approximately $250,000, which comes under scrutiny in 1900 when the company attempts to raise the price of ice in the city.

After Croker’s failure to carry the city in the 1900 United States presidential election and the defeat of his mayoralty candidate, Edward M. Shepard, in 1901, he resigns from his position of leadership in Tammany and is succeeded by Lewis Nixon. He departs the United States in 1905.

Croker operates a stable of thoroughbred racehorses during his time in the United States in partnership with Michael F. Dwyer. In January 1895, they send a stable of horses to England under the care of trainer Hardy Campbell, Jr. and jockey Willie Simms. Following a dispute, the partnership is dissolved in May but Croker continues to race in England. In 1907, his horse Orby wins Britain’s most prestigious race, The Derby. Orby is ridden by American jockey John Reiff whose brother Lester had won the race in 1901. Croker is also the breeder of Orby’s son, Grand Parade, who wins the Derby in 1919.

Croker returns to Ireland in 1905 and dies on April 29, 1922 at Glencairn House, his home in Stillorgan outside Dublin. His funeral, celebrated by South African bishop William Miller, draws some of Dublin’s most eminent citizens. The pallbearers are Arthur Griffith, the President of Dáil Éireann; Laurence O’Neill, the Lord Mayor of Dublin; Oliver St. John Gogarty; Joseph MacDonagh; A.H. Flauley, of Chicago; and J.E. Tierney. Michael Collins, Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State, is represented by Kevin O’Shiel; the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Edmund Bernard FitzAlan-Howard, 1st Viscount FitzAlan of Derwent, is represented by his under-secretary, James MacMahon.

In 1927, J. J. Walsh claims that just before his death Croker had accepted the Provisional Government’s invitation to stand in Dublin County in the imminent 1922 Irish general election.

Major Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith (DSO) of the 2nd Battalion of the

Major Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith (DSO) of the 2nd Battalion of the

The

The

The

The

The

The