Liam Lynch, officer in the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and the commanding general of the Irish Republican Army during the Irish Civil War, is born in the townland of Barnagurraha, County Limerick, on November 9, 1893.

In 1910, at the age of 17, he starts an apprenticeship in O’Neill’s hardware trade in Mitchelstown, where he joins the Gaelic League and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Later he works at Barry’s Timber Merchants in Fermoy. In the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising, he witnesses the shooting and arrest of David, Thomas and Richard Kent of Bawnard House by the Royal Irish Constabulary. After this, he determines to dedicate his life to Irish republicanism. In 1917 he is elected First Lieutenant of the Irish Volunteer Company, which resides in Fermoy.

In Cork in 1919, Lynch re-organises the Irish Volunteers, the paramilitary organisation that becomes the Irish Republican Army (IRA), becoming commandant of the Cork No. 2 Brigade of the IRA during the guerrilla Irish War of Independence. He is captured, along with the other officers of the Cork No. 2 Brigade, in a British raid on Cork City Hall in August 1920. He provides a false name and is released three days later. In September 1920, he and Ernie O’Malley command a force that takes the British Army barracks at Mallow. The arms in the barracks are seized and the building is partially burned. In April 1921, the IRA is re-organised into divisions based on regions. Lynch’s reputation is such that he is made commander of the 1st Southern Division.

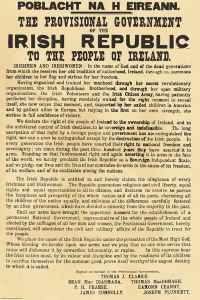

The war formally ends with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty between the Irish negotiating team and the British government in December 1921. Lynch is opposed to the Treaty, on the ground that it disestablishes the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1916 in favour of Dominion status for Ireland within the British Empire. He becomes Chief of Staff of the IRA in March 1922, much of which is also against the Treaty.

Although Lynch opposes the seizure of the Four Courts in Dublin by a group of hardline republicans, he joins its garrison in June 1922 when it is attacked by the newly formed National Army. This marks the beginning of the Irish Civil War. The ‘Munster Republic’ falls in August 1922, when Free State troops land by sea in Cork and Kerry. The Anti-Treaty forces then disperse and pursue guerrilla tactics.

Lynch contributes to the growing bitterness of the war by issuing what are known as the “orders of frightfulness” against the Provisional government on November 30, 1922. This General Order sanctions the killing of Free State Teachta Dála (TDs) and Senators, as well as certain judges and newspaper editors in reprisal for the Free State’s killing of captured republicans. Lynch is heavily criticised by some republicans for his failure to co-ordinate their war effort and for letting the conflict peter out into inconclusive guerrilla warfare. Lynch makes unsuccessful efforts to import mountain artillery from Germany to turn the tide of the war.

In March 1923, the Anti-Treaty IRA Army Executive meets in a remote location in the Nire Valley. Several members of the executive propose ending the civil war. However, Lynch opposes them and narrowly carries a vote to continue the war.

On April 10, 1923, a National Army unit is seen approaching Lynch’s secret headquarters in the Knockmealdown Mountains. Lynch is carrying important papers that could not fall into enemy hands, so he and his six comrades begin a strategic retreat. To their surprise, they run into another unit of 50 soldiers approaching from the opposite side. Lynch is hit by rifle fire from the road at the foot of the hill. Knowing the value of the papers they carry, he orders his men to leave him behind.

When the soldiers finally reach Lynch, they initially believe him to be Éamon de Valera, but he informs them, “I am Liam Lynch, Chief-of-Staff of the Irish Republican Army. Get me a priest and doctor, I’m dying.” He is carried on an improvised stretcher manufactured from guns to “Nugents” pub in Newcastle, at the foot of the mountains. He is later brought to the hospital in Clonmel and dies that evening. He is laid to rest two days later at Kilcrumper Cemetery, near Fermoy, County Cork.

Anti-Treaty forces abandon

Anti-Treaty forces abandon

About 200 Anti-Treaty

About 200 Anti-Treaty