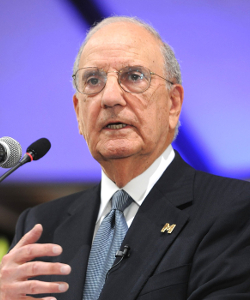

Patrick John Hillery, Irish politician and the sixth President of Ireland, is born in Spanish Point, County Clare on May 2, 1923. He serves two terms in the presidency and, though widely seen as a somewhat lacklustre President, is credited with bringing stability and dignity to the office. He also wins widespread admiration when it emerges that he has withstood political pressure from his own Fianna Fáil party during a political crisis in 1982.

Hillery is educated locally at Milltown Malbay National school before later attending Rockwell College. At third level he attends University College Dublin where he qualifies with a degree in medicine. Upon his conferral in 1947 he returns to his native town where he follows in his father’s footsteps as a doctor.

Hillery is first elected at the 1951 general election as a Fianna Fáil Teachta Dála (TD) for Clare and remains in Dáil Éireann until 1973. During this time, he serves as Minister for Education (1959–1965), Minister for Industry and Commerce (1965–1966), Minister for Labour (1966–1969) and Minister for Foreign Affairs (1969–1973).

Following Ireland’s successful entry into the European Economic Community in 1973, Hillery is rewarded by becoming the first Irishman to serve on the European Commission, serving until 1976 when he becomes President. In 1976 the Fine Gael–Labour Party National Coalition under Liam Cosgrave informs him that he is not being re-appointed to the Commission. He considers returning to medicine; however, fate takes a turn when Minister for Defence Paddy Donegan launches a ferocious verbal attack on President Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, calling him “a thundering disgrace” for referring anti-terrorist legislation to the courts to test its constitutionality. When a furious President Ó Dálaigh resigns, a deeply reluctant Hillery agrees to become the Fianna Fáil candidate for the presidency. Fine Gael and Labour decide it is unwise to put up a candidate in light of the row over Ó Dálaigh’s resignation. As a result, Hillery is elected unopposed, becoming President of Ireland on December 3, 1976.

When Hillery’s term of office ends in September 1983, he indicates that he does not intend to seek a second term, but he changes his mind when all three political parties plead with him to reconsider. He is returned for a further seven years without an electoral contest. After leaving office in 1990, he retires from politics.

Hillery’s two terms as president, from 1976 to 1990, end before the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which sets terms for an end to violence in Northern Ireland. But he acts at crucial moments as an emollient influence on the republic’s policies toward the north and sets a tone that helps pave the way for eventual peace.

Patrick Hillery dies on April 12, 2008, in his Dublin home following a short illness. His family agrees to a full state funeral for the former president. He is buried at St. Fintan’s Cemetery, Sutton, Dublin. In the graveside oration, Tánaiste Brian Cowen says Hillery was “A humble man of simple tastes, he has been variously described as honourable, decent, intelligent, courteous, warm and engaging. He was all of those things and more.”

Former

Former

Members of

Members of