The Easter Rising, also known as the Easter Rebellion, begins in Dublin on April 24, 1916, and lasts for six days. The Rising, organised by seven members of the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, is launched to end British rule in Ireland and establish an independent Irish Republic while the United Kingdom is heavily engaged in World War I. It is the most significant uprising in Ireland since the Irish Rebellion of 1798, and the first armed action of the Irish revolutionary period.

Shortly before midday, members of the Irish Volunteers, led by schoolmaster and Irish language activist Patrick Pearse and joined by the smaller Irish Citizen Army of James Connolly and 200 women of Cumann na mBan, seize key locations in Dublin and proclaim an Irish Republic. The rebels’ plan is to hold Dublin city centre, a large, oval-shaped area bounded by the Grand Canal to the south and the Royal Canal to the north, with the River Liffey running through the middle.

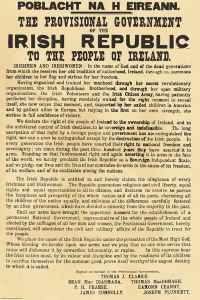

The rebels march to the General Post Office (GPO) on O’Connell Street, Dublin’s main thoroughfare, and occupy the building and hoist two republican flags. Pearse stands outside and reads the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

Elsewhere in Dublin, some of the headquarters battalion under Michael Mallin occupy St. Stephen’s Green, where they dig trenches and barricade the surrounding roads. The 1st battalion, under Edward “Ned” Daly, occupy the Four Courts and surrounding buildings, while a company under Seán Heuston occupies the Mendicity Institution across the River Liffey from the Four Courts. The 2nd battalion, under Thomas MacDonagh, occupies Jacob’s Biscuit Factory. The 3rd battalion, under Éamon de Valera, occupy Boland’s Mill and surrounding buildings. The 4th battalion, under Éamonn Ceannt, occupy the South Dublin Union and the distillery on Marrowbone Lane. From each of these garrisons, small units of rebels establish outposts in the surrounding area.

There are isolated actions in other parts of Ireland, with attacks on the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks at Ashbourne, County Meath and in County Galway, and the seizure of the town of Enniscorthy, County Wexford. Due to a last-minute countermand issued on Saturday, April 22, by Volunteer leader Eoin MacNeill, the number of rebels who mobilise is much lower than expected.

The British Army brings in thousands of reinforcements as well as artillery and a gunboat. There is fierce street fighting on the routes into the city centre, where the rebels put up stiff resistance, slowing the British advance and inflicting heavy casualties. Elsewhere in Dublin, the fighting mainly consists of sniping and long-range gun battles. The main rebel positions are gradually surrounded and bombarded with artillery.

With much greater numbers and heavier weapons, the British Army suppresses the Rising, and Pearse agrees to an unconditional surrender on Saturday, April 29. Almost 500 people are killed during Easter Week. About 54% are civilians, 30% are British military and police, and 16% are Irish rebels. More than 2,600 are wounded. Many of the civilians are killed as a result of the British using artillery and heavy machine guns, or mistaking civilians for rebels. Others are caught in the crossfire in a crowded city. The shelling and the fires leave parts of inner-city Dublin in ruins.

After the surrender the country remains under martial law. About 3,500 people are taken prisoner by the British, many of whom have played no part in the Rising, with 1,800 of them being sent to internment camps or prisons in Britain. Most of the leaders of the Rising are executed following courts-martial. The Rising brings physical force republicanism back to the forefront of Irish politics, which for nearly 50 years has been dominated by constitutional nationalism. It, and the British reaction to it, leads to increased popular support for Irish independence. In December 1918, republicans, represented by the reconstituted Sinn Féin party, win a landslide victory in the general election to the British Parliament. They do not take their seats but instead convene the First Dáil and declare the independence of the Irish Republic, which ultimately leads to the Irish War of Independence.