Mary Leadbeater (née Shackleton), Irish Quaker author and diarist, is born in the planned Quaker settlement of Ballitore, County Kildare, on December 1, 1758. She writes and publishes extensively on both secular and religious topics ranging from translation, poetry, letters, children’s literature and biography. Her accounts of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 provide an insight into the effects of the Rebellion on the community in Ballitore.

Shackleton is the daughter of Richard Shackleton (1726–92) by his second wife, Elizabeth Carleton (1726–66), and granddaughter of Abraham Shackleton, schoolmaster of Edmund Burke. Her parents are Quakers. She keeps a personal diary for most of her life, beginning at the age of eleven and writing in it almost daily. There 55 extant volumes of her diaries in the National Library of Ireland.

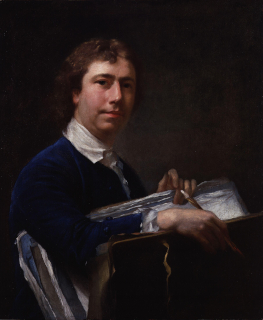

Shackleton is educated, and her literary studies are aided by Aldborough Wrightson, a man who had been educated at Ballitore school and had returned to die there. In 1784, she travels to London with her father and pays several visits to Burke’s town house, where she meets Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Crabbe. She also goes to Beaconsfield, and on her return writes a poem in praise of the place and its owner, which is acknowledged by Burke on December 13, 1784, in a long letter. On her way home she visits, at Selby, North Yorkshire, some primitive Quakers whom she describes in her journal.

On January 6, 1791, Shackleton marries William Leadbeater, a former pupil of her father and a descendent of the Huguenot Le Batre and Gilliard families. He becomes a prosperous farmer and landowner in Ballitore. She spends many years working in the village post office and also works as a bonnet-maker and a herbal healer for the village. The couple lives in Ballitore and have six children. Their daughter Jane dies at a young age from injuries sustained after an accident with a wax taper. Another daughter, Lydia, is a friend and possible patron of the poet and novelist Gerald Griffin.

On her father’s death in 1792, Leadbeater receives a letter of consolation from Burke. Besides receiving letters from Burke, she corresponds with, among others, Maria Edgeworth, George Crabbe, and Melesina Trench. On May 28, 1797, Burke writes one of his last letters to her.

Leadbeater describes in detail the effects of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 on the lives of her family and neighbours in Ballitore. She is in Carlow on Christmas Day 1796 attending a Quaker meeting when the news arrives that the French fleet has been seen off Bantry. She describes the troops marching out of the town and the ensuing confusion in Carlow and Ballitore.

Leadbeater’s first literary work, Extracts and Original Anecdotes for the Improvement of Youth, is published anonymously in 1794 in Dublin. It contains an account of the history of Quakerism and several poems on secular and religious subjects.

In 1808, Leadbeater publishes Poems with a metrical version of her husband’s prose translation of Maffeo Vegio‘s Thirteenth Book of the Æneid. She next publishes in 1811 Cottage Dialogues among the Irish Peasantry, of which four editions, with some alterations and additions, appear by 1813. In 1813, she tries to instruct the rich on a similar plan in The Landlord’s Friend. Intended as a sequel to Cottage Dialogues, in which persons of quality are made to discourse on such topics as beggars, spinning-wheels, and Sunday in the village, Tales for Cottagers, which she brings out in 1814 in conjunction with Elizabeth Shackleton, is a return to the original design. The tales illustrate perseverance, temper, economy, and are followed by a moral play, Honesty is the Best Policy.

In 1822, Leadbeater concludes this series with Cottage Biography, being a Collection of Lives of the Irish Peasantry. The lives are those of real persons, and contain some interesting passages, especially in the life of James Dunn, a pilgrim to Lough Derg. Many traits of Irish country life appear in these books, and they preserve several of the idioms of the English-speaking inhabitants of the Pale. Memoirs and Letters of Richard and Elizabeth Shackleton … compiled by their Daughter is also issued in 1822. Her Biographical Notices of Members of the Society of Friends who were resident in Ireland appears in 1823, and is a summary of their spiritual lives, with a scanty narrative of events. Her last work is The Pedlars, a Tale, published in 1824.

Leadbeater’s best known work, the Annals of Ballitore, is not printed until 1862, when it is brought out with the general title of The Leadbeater Papers (2 vols.) by Richard Davis Webb, a printer who wants to preserve a description on rural Irish life. It tells of the inhabitants and events of Ballitore from 1766 to 1823, and few books give a better idea of the character and feelings of Irish cottagers, of the premonitory signs of the rebellion of 1798, and the Rebellion itself. The second volume includes unpublished letters of Burke and the correspondence with Mrs. Richard Trench and with Crabbe.

Leadbeater dies at Ballitore on June 27, 1826, and is buried in the Quaker burial-ground there.