The Battle of Connor is fought on September 10, 1315, in the townland of Tannybrake just over a mile north of what is now the modern village of Connor, County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is part of the Bruce campaign in Ireland.

Edward Bruce lands in Larne, in modern-day County Antrim, on May 26, 1315. In early June, Donall Ó Néill of Tyrone and some twelve fellow northern Kings and lords meet Bruce at Carrickfergus and swear fealty to him as King of Ireland. Bruce holds the town of Carrickfergus but is unable to take Carrickfergus Castle. His army continues to spread south, through the Moyry Pass to take Dundalk.

Outside the town of Dundalk, Bruce encounters an army led by John FitzThomas FitzGerald, 4th Lord of Offaly, his son-in-law Edmund Butler, Earl of Carrick and Maurice FitzGerald, 4th Baron Desmond. The Scottish push them back towards Dundalk and on June 29 lay waste to the town and its inhabitants.

By July 22 Edmund Butler, the Justiciar in Dublin, assembles an army from Munster and Leinster to join Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster, to fight Bruce. De Burgh refuses to let the government troops into Ulster, fearing widespread damage to his land. Bruce is able to exploit their dispute and defeat them separately.

Bruce slowly retreats north, drawing de Burgh in pursuit. Bruce and his O’Neill allies sack Coleraine, destroying the bridge over the River Bann to delay pursuit. Edward sends word to Fedlim Ó Conchobair that he will support his position as king in Connacht if he withdraws. He sends the same message to rival claimant Ruaidri mac Cathal Ua Conchobair. Cathal immediately returns home, raises a rebellion and declares himself king. De Burgh’s Connacht allies under Felim then follow as Felim leaves to defend his throne. Bruce’s force then crosses the River Bann in boats and attacks. The Earl of Ulster withdraws to Connor.

The armies meet in Connor on September 10, 1315. The superior force of Bruce and his Irish allies defeat the depleted Ulster forces. The capture of Connor permits Bruce to re-supply his army for the coming winter from the stores the Earl of Ulster had assembled at Connor. Earl’s cousin, William de Burgh, is captured, as well as, other lords and their heirs. Most of his army retreats to Carrickfergus Castle, which the pursuing Scots put under siege. The Earl of Ulster manages to return to Connacht.

The government forces under Butler do not engage Bruce, allowing him to consolidate his hold in Ulster. His occupation of Ulster encourages risings in Meath and Connacht, further weakening de Burgh. Despite this, and another Scottish/Irish victory at the Battle of Skerries, the campaign is to be defeated at the Battle of Faughart.

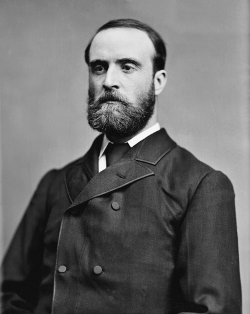

(Pictured: Grave of King Edward Bruce, Faughart, County Louth)