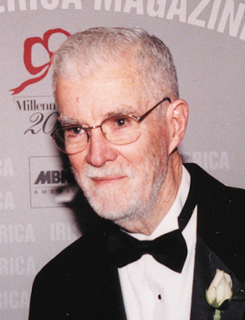

Andrew O’Connor, American Irish sculptor whose work is represented in museums in the United States, Ireland, Britain and France, dies in Dublin on June 9, 1941.

O’Connor is born on June 7, 1874, at Worcester, Massachusetts, the eldest of three sons and two daughters of Andrew O’Connor, a stonecutter from Lanarkshire, Scotland, who becomes a professional sculptor, and Marie Anne O’Connor (née McFadden), of County Antrim. Educated in Worcester public schools, at the age of 14 he becomes apprenticed to his father, helping him to design monuments for cemeteries. He is employed in the early 1890s on sculptural work for the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago World’s Fair), being active in the studio of William Ordway Partridge, and assisting Daniel Chester French on his colossal Statue of the Republic, a landmark of the 1893 Columbian exposition.

Moving to London (1894–98), O’Connor works on bas-reliefs in the studio of the painter John Singer Sargent, who uses him as a model for his mural Frieze of Prophets for the Boston Public Library. His first independent work, Sea Dreams, a relief of a head, is exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1896. Returning to the United States (1898–1903), he becomes a studio assistant of French, through whom he receives his first public commission, for the Vanderbilt Memorial Doors for St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, Manhattan, New York, a project completed in 1902 to wide critical acclaim. He also executes the tympanum and lateral friezes.

Around 1900, O’Connor marries an artist’s model named Nora, by whom he has a daughter. In 1902, he hires as studio model Jessie Phoebe Brown from New Jersey and of County Down parentage. The following year he elopes with her to Paris, where they marry and have four sons, the youngest of whom, Patrick O’Connor, becomes an artist and gallery curator. Jessie continues for many years as his primary model, sitting for the heads of both female and male figures, O’Connor coarsening the features for the latter.

During his years in Paris (1903–14), O’Connor is influenced by the work of Auguste Rodin, whom he befriends. Among his pupils in Paris is the American sculptor and heiress Gloria Vanderbilt Whitney. He continues to fulfil numerous commissions for funerary and public monuments in the United States, an example of the former being the Recuillement in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, near Tarrytown, New York. From 1906 he exhibits annually at the Salon in Paris, where he is the first foreigner to win a second-class medal, for his bronze statue of Gen. Henry Lawton. Included in his only exhibition at the Royal Hibernian Academy (1907) is a bronze relief of the prophet Nehemiah adapted from a panel of the Vanderbilt doors. The relief is subsequently included in his one-man show at the Galerie Hébrard, Paris in 1909.

In 1909, O’Connor wins a competition open to sculptors of Irish descent to execute a monument to Commodore John Barry, the County Wexford-born “father of the American navy,” for Washington, D.C. His design includes a frieze depicting events in Irish history, flanked by a group of three nude Irish emigrants entitled Exile from Ireland, and another group representing the Genius of Ireland, which includes a female figure of the “Motherland.” Probably owing to opposition from the Barry family to the depiction of their ancestor as a rough-and-ready sailor, the commission is not completed. His marble statue of Gen. Lew Wallace (author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ), a plaster of which is exhibited at the Salon in Paris in 1909, is placed by the state of Indiana in the National Statuary Hall in the United States Capitol, Washington, D.C. Another marble, Peace by Justice, is commissioned as a gift from the United States to the Peace Palace in The Hague in 1913.

O’Connor returns with his family to the United States on the outbreak of World War I, and sets up a studio in Paxton, Massachusetts. In 1918, his standing statue of the youthful Abraham Lincoln is placed outside the Illinois State Capitol at Springfield, Illinois. He later presents a marble head of Lincoln to the American ambassador’s residence, Phoenix Park, Dublin. His memorial in Chicago to President Theodore Roosevelt (1919) is commissioned as a tribute to Roosevelt’s associations with the Boy Scouts of America. The design of four standing scouts, modelled on O’Connor’s sons, is exhibited at the Philadelphia Art Alliance in 1920. He becomes an associate of the National Academy of Design, New York in 1919. In the early 1920s he executes an equestrian statue of the Marquis de Lafayette for South Park, at Mount Vernon, Baltimore, Maryland.

Returning to Paris in the mid-1920s, O’Connor becomes the first foreigner to win a gold medal at the Salon des Artistes in 1928, for the marble sculpture Tristan and Iseult, now held in the Brooklyn Museum, New York. The French government makes him a Chevalier of the National Order of the Legion of Honour in 1929. In 1926 he had exhibited a plaster group, Monument aux morts de la Grande Guerre, at the Salon in Paris. The sculpture is requested in 1932 by the people of Dún Laoghaire, County Dublin, as a memorial to Christ the King, O’Connor obligingly altering the interpretation of his iconography. Imposed on a “Tree of life” are three figures of Christ, representing in turn “Desolation,” “Consolation” and “Triumph.” Cast in bronze, throughout World War II the statue remains hidden in Paris to avoid its being melted down for the valuable metal. Transported to Dún Laoghaire in 1949, due to clerical opposition to its unconventional iconography, it is not at first erected, but for years lay on its side in a garden in Rochestown Avenue until its eventual unveiling in 1978 as Triple Cross in Haigh Terrace, where it stands in Moran Park. His other chief work in Ireland is a bronze statue of Daniel O’Connell in the Bank of Ireland, College Green, Dublin. Inspired by Rodin’s famous Monument to Balzac, the work is executed at his studio in a converted stable at Leixlip Castle, County Kildare in 1931–32.

During the 1930s, O’Connor lives and works in London and Ireland, where he has residences at Glencullen House, County Wicklow, and 77 Merrion Square, Dublin. He dies at the latter address on June 9, 1941, and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. His own bronze relief, Le feu sacré, marks the grave. A portrait painting, executed by his son Patrick in 1940, is in Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, which also holds twenty-six sculptures presented by O’Connor late in his life, and posthumously by his family. The collection includes a marble self-portrait bust of 1940, a bronze of the Lafayette cast by the gallery in 1984 from a reduced plaster model presented by the artist, and a bronze group entitled The Victim, on view in Merrion Square Park, from an uncommissioned and uncompleted war memorial conceived by O’Connor under the general title Le Débarquement. The National Gallery of Ireland has the Desolation maquette for the Triple Cross. A centenary exhibition of his work is held at Trinity College Dublin in 1974. His widow dies in Dublin in 1974.

(From: “O’Connor, Andrew” by Lawrence William White and Carmel Doyle, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)

The remaining human inhabitants of the

The remaining human inhabitants of the