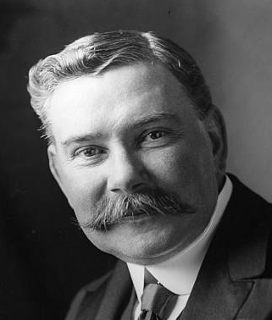

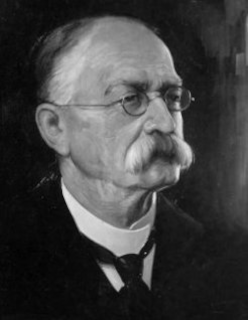

Sir John Henry MacFarland, Irish Australian educationist and churchman, is born in Omagh, County Tyrone, on April 19, 1851.

MacFarland is the elder son of John MacFarland, draper, and his second wife Margaret Jane, daughter of Rev. William Henry, a famous Covenanting Church minister. Both parents are devout Presbyterians, well educated, with strong intellectual interests.

MacFarland attends the local national school until he is 13 when he moves to the Royal Belfast Academical Institution. He is senior scholar in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Queen’s College, Belfast, where he is taught by John Purser. There he earns a BA in 1871 and MA in 1872. He goes on to St. John’s College, Cambridge, for three more years of undergraduate study of mathematics and physics. There he is elected a foundation scholar and earns a second BA, as 25th wrangler, in 1876. He also earns an MA there in 1879.

MacFarland teaches at Repton School in Derbyshire from 1876 to 1880. A decade later, his younger brother Robert, also a Queen’s Belfast and Cambridge mathematics graduate, also teaches at Repton.

The emissaries of the provisional council of Ormond College in the University of Melbourne are impressed with MacFarland. He negotiates a salary of £600 plus the profit from “farming” the college. On March 18, 1881, he becomes the first master of Ormond College, passing the opening-day ordeal in the presence of 440 Presbyterian grandees, clergy and their ladies.

On Sir John Madden‘s death in 1918, MacFarland becomes chancellor of the university and is knighted in 1919. He presides over a period of considerable expansion, working closely with Sir John Monash, vice-chancellor from 1923, and Sir James Barrett.

MacFarland is immensely and properly proud of his careful financial management, but the erstwhile reformers are hardly tender enough in balancing economy with humanity. The professors become increasingly restive about the limited responsibility for academic matters and allocation of resources council allows them. When the issues come to a head in 1928, MacFarland’s prestige is too much for the professoriate who have great respect for his administrative capacity, humanity and reasonableness. Even in his eighties he does not retire as chancellor, probably wisely concluding that his likely successor, Barrett, will prove to be too divisive.

In 1892, MacFarland receives and honorary LLD degree from the Royal University of Ireland.

MacFarland’s reputation as a business manager leads to his directorship from about 1905 of the National Mutual Life Association, serving as chairman from 1928, and of the Trustees Executors and Agency Company. From 1913 he represents the Trustees Executors on the Felton Bequests Committee. He is also the popular chairman from its foundation in 1908 of the Alexandra Club Co. as the members of the leading female social club prefer men to control their finances.

In his younger days MacFarland is a vigorous cyclist and walker in the Australian Alps, Tasmania and New Zealand. By the age of 40 he is spending a month each summer trout-fishing in the South Island of New Zealand. He is also a regular golfer at Royal Melbourne and belongs to the Melbourne Club.

MacFarland dies in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, on July 22, 1935. His remains are cremated following a service at Scots’ Church. The university council minutes:

“Few men in any community, and almost no man in this community, can have won such universal esteem. No evil was ever spoken of him or could be thought of in connection with him; before him evil quailed. The greatest disciple of the greatest of the Greeks called his dead master ‘our friend whom we may truly call the wisest, and the justest, and the best of all men we have ever known’. And many of us can sincerely say that of John Henry MacFarland.”

(From: “Sir John Henry MacFarland (1851-1935)” by Geoffrey Serle, Australian Dictionary of Biography, http://www.adb.anu.edu.au, 1986)