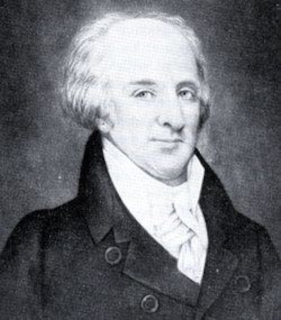

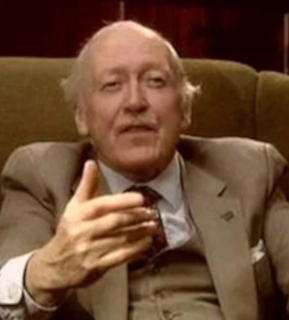

Vincent Gerard Dowling, Irish theatre actor, director and producer, dies at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston on May 10, 2013.

Dowling is born in Kimmage, Dublin, on September 7, 1929, the sixth of four sons and three daughters of William Dowling, a ship’s captain, and his wife Mary (née Kelly). His father is violent toward the family and leaves when he is a toddler. Helped by money provided by a priest, the Dowlings move in 1934 from the basement of his maternal uncle’s flat in Merrion Square, Dublin, to a house in Mount Merrion, County Dublin. In 1942, financial necessity forces the family’s move to a smaller residence in Marlborough Road, Donnybrook, Dublin.

Dowling is educated at St. Mary’s College in Rathmines, Dublin, having previously attended Kilmacud National School and CBS Dún Laoghaire, both in County Dublin. He is a bright student, but with his fees in arrears, the dean of studies induces him to leave school early in September 1945 for a clerkship with the Standard Life Assurance Company. A few years later, he finds his vocation when he accompanies a girlfriend to the academy of acting run by Brendan Smith. He signs up in 1948 for a two-year course during which he performs in and stage-manages academy plays and stage-manages for Smith’s professional company. Upon quitting Standard Life in June 1950, he spends a year touring Ireland with Smith’s company, both as an actor and the touring group’s manager.

Dowling comes to prominence in the 1950s for his role as Christy Kennedy in the long-running radio soap opera, The Kennedys of Castleross, and as a member of the Abbey Theatre company. He returns to the Abbey as artistic director from 1987 to 1990.

Following two months in the United States in 1969 lecturing and directing at Loyola University Chicago, he spends periods during 1972–74 directing for the Missouri Repertory Theatre and lecturing and directing at the University of Missouri – Kansas City. On extended leave from the Abbey, he directs in various American theatres throughout 1975, the year he married Olwen O’Herlihy, daughter of the Irish actor Dan O’Herlihy. After his request for six months leave each year is refused, he quits the Abbey in 1976, having done over a hundred major roles for the company.

In 1976, Dowling becomes a U.S. citizen and is appointed artistic and producing director of the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival (GLSF) in Cleveland, Ohio, from 1976 to 1984, where he directs, produces and acts in many classical works, by William Shakespeare and others. He is credited with discovering actor Tom Hanks. He receives an Ohio Valley Emmy Award for the 1983 PBS broadcast of his 1982 GLSF production of The Playboy of the Western World.

Dowling is visiting professor at the College of Wooster in Ohio during the 1986-87 academic year. He founds the Miniature Theatre of Chester (now the Chester Theatre Company), in Chester, Massachusetts, in 1990.

Dowling marries actress Brenda Doyle in 1952. They have four daughters, including actress Bairbre Dowling, before divorcing in 1975. In 1975, he marries Olwen O’Herlihy, with whom he has a son.

Politician Richard Boyd Barrett is the biological son of Dowling and recording artist and actress Sinéad Cusack from a 1966 relationship while both are at the Abbey Theatre. Boyd Barrett is adopted as an infant. Dowling contacts Boyd Barrett after his connection with Cusack is publicly revealed in 2007. Their relationship is made known after his death.

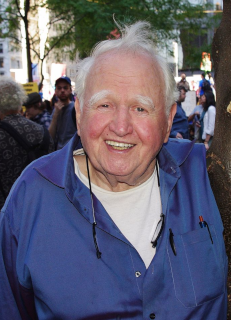

Dowling dies on May 10, 2013, in Massachusetts General Hospital due to complications arising from surgery. Following a funeral service at the First Congregational Church of Chester, his remains are interred in the nearby cemetery.

Dowling receives honorary doctorates from Westfield State University in Massachusetts, and from Kent State University, John Carroll University and the College of Wooster, all in Ohio. His papers, from 1976 onward, are housed at the Kent State University and John Carroll University libraries.