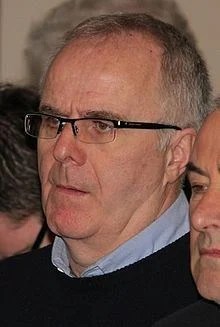

Pat “Beag” McGeown, a volunteer in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) who takes part in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, is born in the Beechmount area of Belfast, Northern Ireland, on on September 3, 1956.

McGeown joins the IRA’s youth wing, Fianna Éireann, in 1970. He is first arrested at the age of 14, and in 1973 he is again arrested and interned in Long Kesh Detention Centre until 1974. In November 1975, he is arrested and charged with possession of explosives, bombing the Europa Hotel, and IRA membership. At his trial in 1976 he is convicted and receives a five-year sentence for IRA membership and two concurrent fifteen-year sentences for the bombing and possession of explosives, and is imprisoned at Long Kesh with Special Category Status.

In March 1978, McGeown attempts to escape along with Brendan McFarlane and Larry Marley. The three have wire cutters and dress as prison officers, complete with wooden guns. The escape is unsuccessful, and results in McGeown receiving an additional six-month sentence and the loss of his Special Category Status.

McGeown is transferred into the Long Kesh Detention Centre’s H-Blocks where he joins the blanket protest and dirty protest, attempting to secure the return of Special Category Status for convicted paramilitary prisoners. He describes the conditions inside the prison during the dirty protest in a 1985 interview:

“There were times when you would vomit. There were times when you were so run down that you would lie for days and not do anything with the maggots crawling all over you. The rain would be coming in the window and you would be lying there with the maggots all over the place.“

In late 1980, the protest escalates and seven prisoners take part in a fifty-three-day hunger strike, aimed at restoring political status by securing what are known as the “Five Demands:”

- The right not to wear a prison uniform.

- The right not to do prison work.

- The right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits.

- The right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week.

- Full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

The strike ends before any prisoners die and without political status being secured. A second hunger strike begins on March 1, 1981, led by Bobby Sands, the IRA’s former Officer Commanding (OC) in the prison. McGeown joins the strike on July 9, after Sands and four other prisoners have starved themselves to death. Following the deaths of five other prisoners, his family authorises medical intervention to save his life after he lapses into a coma on August 20, the 42nd day of his hunger strike.

McGeown is released from prison in 1985, resuming his active role in the IRA’s campaign and also working for Sinn Féin, the republican movement’s political wing. In 1988, he is charged with organising the Corporals killings, an incident where two plain-clothes British Army soldiers are killed by the IRA. At an early stage of the trial his solicitor, Pat Finucane, argues there is insufficient evidence against McGeown, and the charges are dropped in November 1988. McGeown and Finucane are photographed together outside Crumlin Road Courthouse, a contributing factor to Finucane being killed by the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) in February 1989. Despite suffering from heart disease as a result of his participation in the hunger strike, McGeown is a member of Sinn Féin’s Ard Chomhairle and is active in its Prisoner of War Department. In 1993, he is elected to Belfast City Council.

McGeown is found dead in his home on October 1, 1996, after suffering a heart attack. Sinn Féin chairman Mitchel McLaughlin says his death is “a great loss to Sinn Féin and the republican struggle.” McGeown is buried in the republican plot at Belfast’s Milltown Cemetery. His death is often referred to as the “11th hunger striker.” In 1998, the Pat McGeown Community Endeavour Award is launched by Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams, with Adams describing McGeown as “a modest man with a quiet, but total dedication to equality and raising the standard of life for all the people of the city.” A plaque in memory of McGeown is unveiled outside the Sinn Féin headquarters on the Falls Road on November 24, 2001, and a memorial plot on Beechmount Avenue is dedicated to the memory of McGeown, Kieran Nugent and Alec Comerford on March 3, 2002.