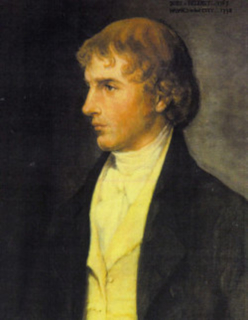

William Steel Dickson, Irish Presbyterian minister and member of the Society of the United Irishmen, dies on December 27, 1824, in Belfast, in what is now Northern Ireland.

Dickson is born on December 25, 1744, the eldest son of John Dickson, a tenant farmer of Ballycraigy, in the parish of Carnmoney, County Antrim. His mother is Jane Steel and, on the death of his uncle, William Steel, on May 13, 1747, the family adds his mother’s maiden name to their own.

In his boyhood, Dickson is educated by Robert White, a Presbyterian minister from Templepatrick and enters University of Glasgow in November 1761. Following graduation, he is apparently employed for a time in teaching, and in 1771 he is ordained as a Presbyterian minister. Until the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, he occupies himself mainly with parochial and domestic duties. His political career begins in 1776, when he speaks and preaches against the “unnatural, impolitic and unprincipled” war with the American colonies, denouncing it as a “mad crusade.” On two government fast-days his sermons on “the advantages of national repentance” (December 13, 1776), and on “the ruinous effects of civil war” (February 27, 1778) create considerable excitement when published. Government loyalists denounce Dickson as a traitor.

Political differences are probably at the root of a secession from his congregation in 1777. The seceders form a new congregation at Kircubbin, County Down, in defiance of the authority of the general synod.

In 1771 Dickson marries Isabella Gamble, a woman of some means, who dies on July 15, 1819. They have at least eight children, but he outlives them all. One of his sons is in the Royal Navy and dies in 1798.

Dickson enters with zest into the volunteer movement of 1778, being warmly in favour of the admission of Roman Catholics to the ranks. This is resisted “through the greater part of Ulster, if not the whole.” In a sermon to the Echlinville volunteers on March 28, 1779, he advocates the enrolment of Catholics and though induced to modify his language in printing the discourse, he offends “all the Protestant and Presbyterian bigots in the country.” He is accused of being a papist at heart, “for the very substantial reason, among others, that the maiden name of the parish priest’s mother was Dickson.”

Though the contrary has been stated, Dickson is not a member of the Volunteer conventions at Dungannon in 1782 and 1783. He throws himself heart and soul into the famous election for County Down in August 1783, when the families of Hill and Stewart, compete for the county seat in Parliament. He, with his forty-shilling freeholders, fails to secure the election of Robert Stewart. But in 1790 he successfully campaigns for the election of Stewart’s son, better known as Lord Castlereagh. Castlereagh proves his gratitude by referring at a later date to Dickson’s popularity in 1790, as proof that he was “a very dangerous person to leave at liberty.”

In December 1791, Dickson joins Robert White’s son, John Campbell White, taking the “test” of the first Society of United Irishmen, organised in October in Belfast following a meeting held with Theobald Wolfe Tone, Protestant secretary of the Catholic Committee in Dublin. According to Dickson himself, he attends no further meetings of the Society but devotes himself to spreading its principles among the volunteer associations, in opposition to the “demi-patriotic” views of the Whig Club.

At a great volunteer meeting in Belfast on July 14, 1792, Dickson opposes a resolution for the gradual removal of Catholic disabilities and assists in obtaining a unanimous pledge in favour of total and immediate emancipation. Parish and county meetings are held throughout Ulster, culminating in a provincial convention at Dungannon on February 15, 1793. He is a leading spirit at many of the preliminary meetings, and, as a delegate from the Barony of Ards, he has a chief hand in the preparation of the Dungannon resolutions. Their avowed object is to strengthen the throne and give vitality to the constitution by “a complete and radical reform.” He is nominated on a committee of thirty to summon a national convention. The Irish parliament goes no further in the direction of emancipation than the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1793, which receives the royal assent on April 9, and remains unextended until 1829. While the passing of Lord Clare‘s Convention Act, still in force, makes illegal all future assemblies of delegates “purporting to represent the people, or any description of the people.”

In March and April 1798, Dickson is in Scotland arranging some family affairs. During his absence plans are made for an insurrection in Ulster, and soon after his return he agrees to take the place of Thomas Russell, who had been arrested, as adjutant-general of the United Irish forces for County Down. A few days before the county is to rise, he is himself arrested at Ballynahinch.

Dickson is conveyed to Belfast and lodged in the “black hole” and other prisons until August 12 when he is removed to a prison ship with William Tennant, Robert Hunter, Robert Simms, David Bailie Warden and Thomas Ledlie Birch, and detained there amid considerable discomfort. On March 25, 1799, Dickson, Tennant, Hunter, and Simms join the United Irish “State Prisoners” on a ship bound for Fort George, Highland prison in Scotland. This group, which includes Samuel Neilson, Arthur O’Connor, Thomas Russell, William James MacNeven, and Thomas Addis Emmet, arrives in Scotland on April 9, 1799. He spends two years there.

Unlike the more high-profile prisoners like O’Connor and MacNeven who are not released until June 1802, Tennant, Dickson, and Simms are permitted to return to Belfast in January 1802.

Dickson returns to liberty and misfortune. His wife has long been a helpless invalid, his eldest son is dead, his prospects are ruined. His congregation at Portaferry had been declared vacant on November 28, 1799. William Moreland, who had been ordained as his successor on June 16, 1800, at once offers to resign, but Dickson will not hear of this. He has thoughts of emigration but decides to stand his ground. At length, he is chosen by a seceding minority from the congregation of Keady, County Armagh, and installed minister on March 4, 1803.

Dickson’s political engagement ends with his attendance on September 9, 1811, of a Catholic meeting in Armagh, on returning from which he is cruelly beaten by Orangemen. In 1815 he resigns his charge in broken health and henceforth subsists on charity. Joseph Wright, an Episcopalian lawyer, gives him a cottage rent-free in the suburbs of Belfast, and some of his old friends make him a weekly allowance. His last appearance in the pulpit is early in 1824. He dies on December 27, 1824, having just passed his eightieth year, and is buried “in a pauper’s grave” at Clifton Street Cemetery, Belfast.