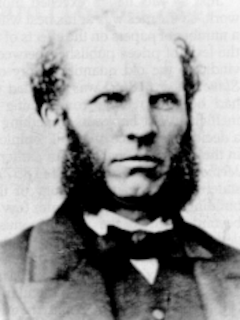

James Orr, weaver, radical, and poet, dies on April 24, 1816.

Orr is the son of James Orr, who farms a few acres and is a linen weaver. His mother’s name is unknown. They live in the small village of Ballycarry, in the parish of Broadisland, County Antrim. He is an only child, born when his parents are middle-aged. They are unwilling to risk sending him to school, so they carefully educate him at home, his father having been very well educated. A near-contemporary source George Pepper (1829), claims that the youngster is something of a prodigy, able to read Spectator essays at the age of six. Later in life, partly thanks to membership of a local reading society, he is remarkably well read. Handloom weavers are reputedly one of the most literate and politically radical groups in the period, and he certainly fits the stereotype. Pepper also claims that William Orr is James Orr’s uncle, and that the younger man lives for three years with William Orr and his family, where his literary talents are nurtured and where he develops an interest in radical politics. Other sources do not support this account, but if there is a relationship it might explain an almost morbid interest in assizes, executions, and gallows, evident in several poems. This also might have been prompted by witnessing William Orr’s trial and execution.

Pepper “heard from good authority” that Orr in 1797 is secretary to the Antrim Association, of which William Orr is president; presumably this means the Society of United Irishmen. He sings a patriotic song called “The Irishman,” one of his most celebrated compositions, at a meeting of that body. The earliest publications traced are poems published pseudonymously (1796–97) in the Northern Star newspaper. This paper, edited by Samuel Neilson, is sympathetic to United Irish views, and it is clear that Orr, like many of his neighbours, is actively involved in the 1798 rebellion. Several poems dealing with the events of June 1798, provide a rare participant’s perspective. He takes part in the skirmish at Donegore, and flees after the defeat at the Battle of Antrim. Local sources record his successful efforts to prevent cruelty and looting by his colleagues. He goes into hiding in an Irish-speaking area, perhaps in the Glens of Antrim or in the Sperrin Mountains. After a short time, he escapes to the United States, but unlike many of his former comrades he finds himself unable to settle there, and very soon returns home to Ballycarry, and thenceforth makes his living as a weaver. In 1800, he seeks to join the militia set up to counter a feared Napoleonic invasion, but the local gentry in command rejects his application because of his United Irish associations.

Orr’s first verses are composed at meetings of a local singing school, where rival versifiers produce impromptu verses for the company to sing to the psalm tunes being practised, and he later writes songs for masonic meetings. He publishes poems in the Belfast newspapers. A few carefully written essays on morality and education, signed “Censor, Ballycarry,” are apparently also his work. A collection of poems is published in 1804, with almost 400 subscribers, and another selection is published in 1817 after his death by his friend Archibald McDowell. Orr had requested that the proceeds should go to help the poor of Ballycarry. His poems are an excellent source of information about the life and concerns of a fairly humble stratum of late eighteenth-century Ulster society.

Many of Orr’s best poems deal with subjects of interest to his community – weaving, social life, and farming – and are written in the Scots language still widely spoken in the area. He expertly uses Scots stanza forms, and joyously participates in the almost competitive composition of verse typical of the Scots tradition. Several of his poems rework themes found in Robert Burns or other earlier writers. His An Irish Cottier’s Death and Burial is derived from a Burns poem, The Cottier’s Saturday Night, but later critics acknowledge that the Orr poem is much more successful. He and his friend Samuel Thomson are pioneers in the use of written Scots in Ulster and are regarded as the two most skillful Scots poets in Ulster. Both are celebrated in their day, and their work in Scots has been rediscovered in the twentieth-century revival of interest in the traditional literature and history of the north of Ireland.

Orr’s verse in standard English is equally competent, even more ambitious and almost as interesting. The best of his work, particularly in Scots, is characterised by pleasing cadences and assured control of tone and technique. His novel and generally impressive experiments with soliloquies, verse epistles, and versified direct speech, in English and Scots, parallel his interest in extending the registers in which he could use the vernacular Scots language. He seems not to have known of William Wordsworth‘s poetry, but, apparently independently and arguably more successfully, produces verse written in “the language really used by men” (Wordsworth, preface to Lyrical Ballads (1798)). As well as fascinating foreshadowings of romanticism, his work more often reveals the influence of the enlightenment and of New Light presbyterianism. He is a member of the congregation of the Rev. John Bankhead, whose theological views are decidedly liberal, tending even towards unitarianism. His poems provide a great deal of evidence on his reading, interests, radical aspirations and convictions; and in them and in the prose essays, the reader encounters a humane and generous personality. Like many other United Irishmen, he is an enthusiastic freemason, and believes that freemasonry and education will help to usher in a peaceful millennium. His poetry reveals humanitarian concerns, not yet common in the period. He opposess slavery and cruelty to animals and children and expresses support for a contemporary popular rising in Haiti. In 1812, he signs a petition in favour of Catholic emancipation.

Orr never marries. His friend McDowell believes that the resulting lack of domestic comforts drives the poet to socialise in taverns, and it is said that local fame and popularity encourages his excessive drinking. He suffers from ill health in later life. A neglected cold in 1815 leads to tuberculosis. He dies on April 24, 1816, and is buried in the old Templecorran graveyard at Ballycarry. Some years later, freemasons erect an impressive monument over the grave.

Orr’s poems are republished by a group of local enthusiasts in 1935. Another selection appears in 1992. A plaque put up by the local district council commemorates “the bard of Ballycarry,” probably the most significant eighteenth-century English-language poet in Ulster.

(From: “Orr, James” by Linde Lunney, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)