Daniel O’Connell, lawyer who becomes the first great 19th-century Irish nationalist leader and is known as “The Liberator,” dies in Genoa, Italy on May 15, 1847. Throughout his life, he campaigns for Catholic emancipation, including the right for Catholics to sit in the Westminster Parliament and the repeal of the Act of Union which combines Great Britain and Ireland.

Compelled to leave the Roman Catholic college at Douai, France, when the French Revolution breaks out, O’Connell goes to London to study law, and in 1798 he is called to the Irish bar. His forensic skill enables him to use the courts as nationalist forums. Although he has joined the Society of United Irishmen, a revolutionary society, as early as 1797, he refuses to participate in the Irish Rebellion of the following year. When the Act of Union takes effect on January 1, 1801, and abolishes the Irish Parliament, he insists that the British Parliament repeal the anti-Catholic laws in order to justify its claim to represent the people of Ireland. From 1813 he opposes various Catholic relief proposals because the government, with the acquiescence of the papacy, has the right to veto nominations to Catholic bishoprics in Great Britain and Ireland. Although permanent political organizations of Catholics are illegal, O’Connell sets up a nationwide series of mass meetings to petition for Catholic emancipation.

On May 12, 1823, O’Connell and Richard Lalor Sheil found the Catholic Association, which quickly attracts the support of the Irish priesthood and of lawyers and other educated Catholic laymen and which eventually comprises so many members that the government cannot suppress it. In 1826, when it is reorganized as the New Catholic Association, it causes the defeat of several parliamentary candidates sponsored by large landowners. In County Clare in July 1828, O’Connell himself, although as a Catholic ineligible to sit in the House of Commons, defeats a man who tries to support both the British government and Catholic emancipation. This result impresses on the British prime minister, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, the need for making a major concession to the Irish Catholics. Following the passage of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, O’Connell, after going through the formality of an uncontested reelection, takes his seat at Westminster.

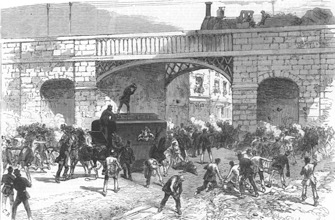

In April 1835, he helps to overthrow Sir Robert Peel’s Conservative ministry. In the same year, he enters into the “Lichfield House compact,” whereby he promises the Whig Party leaders a period of “perfect calm” in Ireland while the government enacts reform measures. O’Connell and his Irish adherents, known collectively as “O’Connell’s tail,” then aid in keeping the weak Whig administration of William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, in office from 1835 to 1841. By 1839, however, O’Connell realizes that the Whigs will do little more than the Conservatives for Ireland, and in 1840 he founds the Repeal Association to dissolve the Anglo-Irish legislative union. A series of mass meetings in all parts of Ireland culminate in O’Connell’s arrest for seditious conspiracy, but he is released on appeal in September 1844 after three months’ imprisonment. Afterward his health fails rapidly, and the nationalist leadership falls to the radical Young Ireland group.

O’Connell dies at the age of 71 of cerebral softening in 1847 in Genoa, Italy, while on a pilgrimage to Rome. His time in prison has seriously weakened him, and the appallingly cold weather he has to endure on his journey is probably the final blow. According to his dying wish, his heart is buried at Sant’Agata dei Goti, then the chapel of the Irish College, in Rome and the remainder of his body in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin, beneath a round tower.