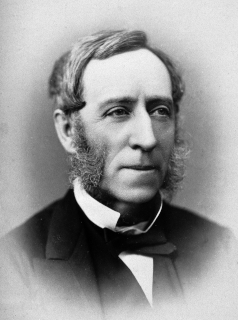

Lucius Henry Gwynn, Irish academic and sportsman who is noted for his prowess in both rugby union football and cricket, dies in Davos Platz, Switzerland, on December 23, 1902.

Gwynn is born in Ramelton, County Donegal, on May 5, 1873. He is a member of a family well known in Dublin at the time for its academic and sporting achievements. He is the fourth son of the Very Rev. John Gwynn, Regius Professor of Divinity at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), and Lucy Josephine, daughter of the Irish patriot William Smith O’Brien. He and his three immediate younger brothers, Arthur, Robin and Jack, all in turn captain their school and university cricket teams and play the game at first class level. He is also a talented rugby player.

Gwynn’s academic career outshines even his sporting achievements. He enters Trinity College Dublin as a foundation Scholar and achieves a double first in his degree finals. In 1899 he is elected a Fellow of Trinity College and commences what promises to be a distinguished academic career.

At school Gwynn is mainly a bowler, his brother Arthur being the superior bat, though this inequality is ironed out at university. He is captain of the Dublin University Cricket Club XI for two seasons, 1894 and 1895, then plays under Arthur’s captaincy. The three brothers make up a formidable threesome in those years.

Primarily noted for his bowling prowess during early outings with the Dublin University XI, Gwynn takes 44 wickets at an average of 8.14 in Trinity’s annus mirabilis of 1893, a season which witnesses victories over Leicestershire, Oxford University, Warwickshire (dismissed for a paltry total of 15 runs) and a draw against Essex.

Gwynn, a right-handed batsman, who records the highest first-class average (56.87) among those batsmen who complete ten innings or more during the English season of 1895, enjoys another remarkably productive season in 1896, plundering over a thousand runs in Trinity flannels, a superlative effort complemented by a haul of 93 wickets at 9.37. His irrepressible form reputedly earns him an invitation to represent England against Australia in the second Ashes Test at Old Trafford in July 1896. However, concurrent university examinations render him unable to participate. Instead, English cricket is introduced to the wizardry of K. S. Ranjitsinhji, who takes Gwynn’s place.

Gwynn makes his debut for Ireland against I Zingari in July 1892 and goes on to play for Ireland 13 times, his last game coming in May 1902 against Marylebone. Two of his matches for Ireland have first-class status.

Gwynn also plays first-class cricket in two Gentlemen v Players matches, representing the gentlemen, and four matches for Dublin University in 1895, for whom he makes his top score of 153 not out against Leicestershire. In all, he amasses 3,195 runs and 311 wickets for Dublin University, in addition to 499 runs and 14 wickets for Ireland.

Remarkably, Gwynn also represents Ireland seven times at rugby union, debuting against Scotland at Belfast in February 1893. He features in all three legs of Ireland’s 1894 Triple Crown-winning campaign.

In 1901 Gwynn marries Katharine Rawlins of Bristol. He is already suffering from persistent symptoms of debility and fatigue. A few months later a Harley Street physician diagnoses tuberculosis. He is admitted to a sanatorium at Davos Platz in Switzerland, but the illness has progressed too far for any treatment to succeed. He dies on December 23, 1902, at the age of 29. The couple’s only child, a daughter named Rhoda, is born in September 1902, just three months before his death.