Liam Ó Briain, Irish language expert and political activist, dies on August 12, 1974, in Cabinteely, County Dublin.

Christened as William O’Brien, Ó Briain is born at 10 Church Street, North Wall, Dublin, on September 16, 1888, the seventh child of Arthur O’Brien, clerk, and Mary O’Brien (née Christie), who is from County Meath. He takes an interest in the Irish language from an early age and begins learning Irish by himself from a grammar book, as it is not encouraged by his teachers at the Christian Brothers’ O’Connell School nor spoken by his parents. While still at the O’Connell School, he starts using the Irish version of his name. He also attends meetings of the Gaelic League, then attends University College Dublin (UCD) on a scholarship, where he studies French, English and Irish, receiving a BA (1909) and an MA (1910).

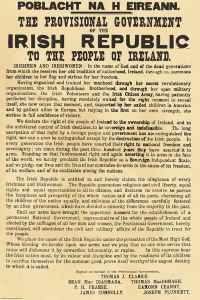

UCD decides to start awarding one annual scholarship for overseas travel in 1911, and Ó Briain wins the first one, using it to visit Germany and study under Kuno Meyer and Rudolf Thurneysen. After three years, he returns home, where he rejoins the Gaelic League and begins teaching French at UCD. He also joins the Irish Volunteers then, the following year, Seán T. O’Kelly convinces him to join the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

During the 1916 Easter Rising, Ó Briain sees action with the Irish Citizen Army. He comes into conflict with his commander, Michael Mallin, as he wants to pursue a strategy without the Dublin brigade being “cooped up in the city.” However, Mallin overrules him and insists they should focus on taking Dublin Castle. He spends two months in Wandsworth Prison in London and six months in Frongoch internment camp in Wales before being released to discover that he has been fired from his job. However, he quickly obtains a professorship in Romance languages at University College Galway (UCG).

Around this time, Ó Briain joins Sinn Féin, and he stands unsuccessfully for the party in Mid Armagh at the 1918 United Kingdom general election in Ireland, taking 5,689 votes. His campaign leads, indirectly, to his arrest and three months in jail in Belfast. In 1920, following his release, he is appointed a judge in the then-illegal republican court system in Galway, and visits both France and Italy to try to source weapons for the Irish Republican Army (IRA). In November 1920, he is arrested in the UCG dining room by Black and Tans, and is imprisoned for thirteen months, first in Galway and then in the Curragh camp in County Kildare, thereby missing the conclusion of the Irish War of Independence. By the time he is released, the Anglo-Irish Treaty has been signed. He supports the treaty and takes no further part in militant activity.

In the newly independent Ireland, Ó Briain remains a professor at Galway. He also stands in the 1925 Seanad election, although he is not successful. He is the founding secretary of the Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe theatre, also acting in many of its productions, and spends much time translating works from English and the Romance languages into Irish. He stands to become president of UCG in 1945, but is not elected, and in the 1940s and 1950s is best known for his many appearances on television and radio.

From his retirement in 1959, Ó Briain lives in Dublin. In 1974, the National University of Ireland (NUI) confers an honorary doctorate on him. He dies on August 12, 1974, at St. Gabriel’s Hospital, Cabinteely, County Dublin. His funeral to Glasnevin Cemetery is almost a state occasion, with a huge attendance of public figures, and a military firing party at the graveside, where the oration is given by Micheál Mac Líammóir and a lesson is read by Siobhán McKenna. For days after his death, the newspapers carry tributes to his many-sided career and personality. On the one hundredth anniversary of his birth, Proinsias Mac Aonghusa and Art Ó Beoláin write commemorative articles in Feasta.

On September 1, 1921, Ó Briain marries Helen Lawlor, of Dublin, who dies two years before him. The couple’s only child is Eibhlín Ní Bhriain, who is a journalist for The Irish Times and other periodicals.