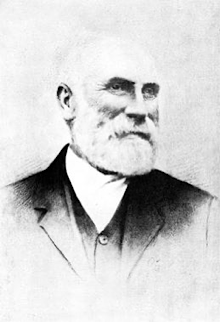

Andrew Joseph Kettle, a leading Irish nationalist politician, progressive farmer, agrarian agitator and founding member of the Irish National Land League, is born on September 26, 1833, in Drynam House, Swords, County Dublin.

Kettle is one among six children of Thomas Kettle, a prosperous farmer, and his wife, Alice (née Kavanagh). His maternal grandmother, Mary O’Brien, had smuggled arms to United Irishmen in the district in 1798, while her future husband, Billy Kavanagh, had been a senior figure in the movement. He is educated at Ireland’s most prestigious Catholic boarding school, Clongowes Wood College. His education is cut short when he is called to help full-time on the farm. Though an autodidact and always a forceful writer, he is beset later by an exaggerated sense of his “defective education and want of talking powers.” Fascinated by politics, he enjoys the repeal excitement of 1841–44 and in his late teens speaks once or twice at Tenant Right League meetings in Swords. Through the 1850s and most of the 1860s he sets about expanding the family farm into a composite of fertile holdings in Swords, St. Margaret’s, Artane, and Malahide (c.150 acres). Getting on well with the Russell-Cruise family of Swords, his first landlords, he benefits from a favourable leasehold arrangement on their demesne in the early 1860s. The farm is mostly in tillage, though Kettle also raises some fat cattle and Clydesdale horses, which he eventually sells to Guinness’s.

Kettle first enters politics in 1867, when he disagrees with John Paul Byrne of Dublin Corporation in public and in print over the right of graziers to state aid during an outbreak of cattle distemper. In 1868, he joins an agricultural reform group initiated by Isaac Butt. He becomes friendly with Butt and later claims to have converted him to support tenant-right. His memoirs, which are somewhat egocentric, contain a number of such questionable claims. It is, however, the case that he habitually writes up, for his own use, cogent summaries of the direction of current political tendencies, which sometimes become useful confidential briefs for Butt and later Charles Stewart Parnell. He is among the published list of subscribers to the Home Rule League in July 1870.

In 1872, disappointed by the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870, Kettle organises a Tenants’ Defence Association (TDA) in north County Dublin, soon sensing the need for a central body to coordinate the grievances of similar groups around the country. The Dublin TDA effectively acts as this central body, under his guidance as honorary secretary. At the 1874 United Kingdom general election in Ireland, the Dublin TDA decides to challenge the electoral control of certain corporation interests in County Dublin. Kettle secures the cautious approval of Cardinal Paul Cullen for any candidate supporting the principle of denominational education. He is also one of a deputation to ask Parnell to fight the constituency, which the latter loses. He becomes closely acquainted with Parnell, who frequently attends Dublin TDA meetings after his election for Meath in April 1875.

Taking a sombre view of the threat of famine in the west of Ireland after evidence of crop failure appears in early summer 1879, Kettle calls a conference of TDA delegates at the European Hotel in Bolton Street, Dublin, in late May. After a heated debate in which a proposal for a rent strike is greatly modified, Parnell comes to seek Kettle’s advice on whether to become involved in the evolving land agitation in County Mayo. Kettle urges him to go to the Westport meeting set for June 8, 1879, and claims later to have stressed in passing that “if you keep in the open you can scarcely go too far or be too extreme on the land question.” If the incident is correctly recounted, this is a most important statement, which virtually defines Parnell’s oratorical strategy throughout the land war. In October 1879, Kettle agrees to merge the TDA with a new Irish National Land League, set up at a meeting in the Imperial Hotel, Dublin, chaired by Kettle. As honorary secretary of the Land League, Kettle frankly admits that he is able to attend meetings without “the necessity of working.” His attendance is, however, among the most regular of all League officers, with him taking part in 73 of 107 meetings scheduled between December 1879 and October 1881.

In March 1880, Kettle disputes Michael Davitt‘s reluctance to use League funds in the general election. He canvasses vigorously together with Parnell in Kildare, Carlow, and Wicklow and is later pressed by his party leader into standing for election in County Cork, though aware that the local tenant movement has already prepared their own candidates. His association with Parnell antagonises the catholic hierarchy in Munster, who issues a condemnation of his candidacy. The hurly-burly of this election creates the persistent impression that Kettle is anti-clerical in politics, and he is defeated by 151 votes.

On a train journey to Ballinasloe in early April 1880, Kettle confides to Parnell his idea that land purchase can be facilitated by the recovery of tax allegedly charged in excess on Ireland by the British government since the act of union. At League meetings in June and July 1880, he advances his “catastrophist” plan: to cease attempts to prevent the development of an irresistible crisis among the Irish smallholding population, by diverting the application of League funds from general relief solely to the aid of evicted tenants, who might be temporarily housed “encamped like gypsies and the land lying idle,” in the belief that the British government will thereby be compelled to introduce radical remedial legislation. Smallholders do not have enough faith in either League or parliamentary politicians to listen.

At a meeting of the League executive in London and in Paris, before and after Davitt’s arrest on February 3, 1881, Kettle presents his plan that the parliamentary party should, if faced with coercive legislation, withdraw from Westminster, “concentrate” in Ireland, and call a general rent strike. Republicans on the League executive continually find themselves embarrassed by Kettle’s radical calls to action motivated solely by the project of agrarian reform. Parnell is later supposed to have lamented party failure to execute the plan at this juncture.

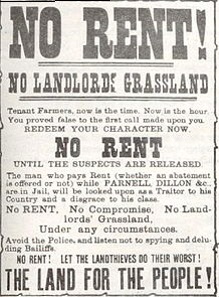

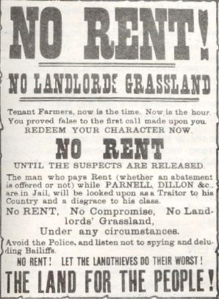

Kettle is arrested in June 1881 for calling for a collective refusal of rent. After two weeks in Naas jail he is transferred to Kilmainham Gaol, where in October he is, with some misgivings, one of the signatories to the No Rent Manifesto. Discharged from Kilmainham in late December 1881 owing to poor health, he returns principally to work on the family farm for most of the 1880s, though he claims to have formulated a draft solution for the plight of the agricultural labourer and “pushed it through” in correspondence with Parnell. He reemerges in 1890 to defend Parnell after the divorce scandal breaks. Attempting to establish a new ”centre” party independent of extreme Catholic and Protestant interests, he stands for election as a Parnellite at the 1891 County Carlow by-election, where he is comprehensively beaten, having endured weeks of insinuating harangues by Tim Healy, and raucous mob insults to the din of tin kettles bashed by women and children at meetings around the county. He is intermittently involved in County Dublin politics in the 1890s and 1900s and maintains a brusque correspondence on matters of the day in the national press.

Kettle dies on September 22, 1916, at his residence, St. Margaret’s, County Dublin, anguished by the death on September 9 of his brilliant son, Tom Kettle, near the village of Ginchy during the Battle of the Somme. He is buried at St. Colmcille’s cemetery, Swords.

Kettle marries Margaret McCourt, daughter of Laurence McCourt of Newtown, St. Margaret’s, County Dublin, farmer and agricultural commodity factor. They have five sons and six daughters.

The

The