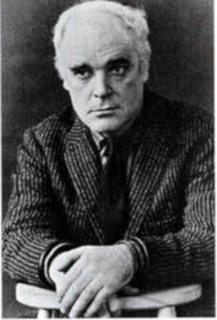

Brian Keenan, Northern Irish writer, is released by the Islamic Jihad Organization on August 24, 1990 after having spent 52 months as a hostage in Beirut, Lebanon. His works include the book An Evil Cradling, an account of the four and a half years he spends as a hostage.

Keenan is born into a working-class family in East Belfast on September 28, 1950. He leaves Orangefield High School early and begins work as a heating engineer. However, he continues an interest in literature by attending night classes and in 1970 gains a place at the University of Ulster in Coleraine. Other writers there at the time included Gerald Dawe and Brendan Hamill. In the mid 1980s he returns to the Magee College campus of the university for postgraduate study. Afterwards he accepts a teaching position at the American University of Beirut, where he works for about four months.

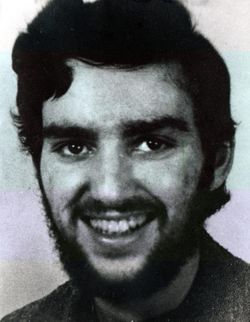

On the morning of April 11, 1986 Keenan is kidnapped by the Islamic Jihad Organization. After spending two months in isolation, he is moved to a cell shared with the British journalist John McCarthy. He is kept blindfolded throughout most of his ordeal, and is chained by hand and foot when he is taken out of solitary.

The British and American governments at the time have a policy that they will not negotiate with terrorists and Keenan is considered by some to have been ignored. Because he is travelling on both Irish and British passports, the Irish government makes numerous diplomatic representations for his release, working closely with the Iranian government. Throughout the kidnap they also provide support to his two sisters, Elaine Spence and Brenda Gillham, who are spearheading the campaign for his release. He is released from captivity to Syrian military forces on August 24, 1990 and is driven to Damascus. There he is handed over by the Syrian Foreign Ministry to the care of Irish Ambassador, Declan Connolly. His sisters are flown by Irish Government executive jet to Damascus to meet him and bring him home to Northern Ireland.

An Evil Cradling is an autobiographical book by Keenan about his four years as a hostage in Beirut. The book revolves heavily around the great friendship he experiences with fellow hostage John McCarthy, and the brutality that is inflicted upon them by their captors. It is the 1991 winner of The Irish Times Literature Prize for Non-fiction and the Christopher Ewart-Biggs Memorial Prize.

Keenan returns to Beirut in 2007 for the first time since his release 17 years earlier, and describes “falling in love” with the city.

Brian Keenan now lives in Dublin.