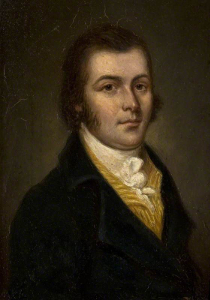

William Thompson, Irish naturalist celebrated for his founding studies of the natural history of Ireland, especially in ornithology and marine biology, is born on December 2, 1805, in the booming maritime city of Belfast.

Thompson is the eldest son of William Thompson, a prosperous linen merchant, and Elizabeth Thompson (née Callwell). He has at least two older sisters and several younger brothers. His mother’s father is Robert Callwell, a printer, book-collector, partner in the Commercial Bank, Belfast, and one of the owners of the Northern Star newspaper.

After attending the Royal Belfast Academical Institution (RBAI) from 1818, Thompson is apprenticed in the linen business of William Sinclair in 1821. When his apprenticeship ends, he goes with his cousin George Langtry, later a wealthy shipowner, on a four-month tour (May–September 1826) of the Low Countries, the Rhine, Switzerland, and Italy. On his return to Belfast, he sets up his own business in linen bleaching. Despite early success, losses are incurred. As family and economic circumstances change, he increasingly concentrates on his natural history studies. By 1831 he has given up business. A self-taught naturalist, related by ties of kinship or friendship to most of the liberal and cultivated families of the “northern Athens,” he is shy and fastidious, but is persuaded in 1826 to join the Belfast Natural History Society by its founder, his friend James Lawson Drummond. He reads his first scientific paper, The Birds of the Copeland Islands, to the society on August 13, 1827. In that year he becomes a member of the Belfast Natural History Society’s council, and in 1833 he is chosen as one of the society’s vice-presidents. He is president from 1843 until his death.

Thompson becomes the most important naturalist in mid nineteenth-century Ireland. From 1827 to 1852 he contributes almost eighty papers on Irish natural history to the Magazine of Zoology and Botany and the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. From 1836 to 1851 he contributes to The Magazine of Natural History. Invited to travel to the Levant and the Aegean Sea in April–July 1841 with Edward Forbes, professor of natural history at the University of Edinburgh, on HMS Beacon, he observes twenty-three species of birds on migratory flights and publishes “Notice of migratory birds” in The Annals of Natural History. His authoritative observations add considerably to knowledge of the still-to-be-ascertained details of migratory patterns. Indeed, some people refuse to believe, even at that date, that birds do migrate. He publishes other papers in the same journal during 1841–43. At a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Glasgow in 1840 his Report on the fauna of Ireland (Vertebrata) attracts favourable notice. He presents and publishes a second and final part enumerating the invertebrates at the Cork meeting of the British Association in August 1843. The two reports form the most complete catalogue of Irish fauna yet published. Thanks to an assiduous correspondence with a network of informants, as well as his own extensive observations, he adds perhaps more than 800 species to Irish fauna lists.

Thompson’s chief work, The Natural History of Ireland, becomes the standard text in Irish zoology in the nineteenth century. The first three volumes, published between 1849 and 1851, deal with birds, particularly their habits and habitats rather than physical descriptions. He is one of the first naturalists to note the effects of industrialisation and other human activities on birdlife. He leaves instructions for his manuscripts on the remaining vertebrates and all the invertebrates to be prepared for publication by Robert Patterson and James Ramsey Garrett. Robert Ball and George Dickie also assist. His notes, though detailed and comprehensive, all require checking, and are found on tiny scraps of paper, even scribbled on the flaps of old envelopes. James Thompson of Macedon, Belfast, painstakingly gums them all into blank notebooks to facilitate the work of his brother’s literary executors, who preface the posthumous publication in 1856 with a lengthy memoir of their friend.

From about 1820 to 1852 Thompson lives with his mother at 1 Donegall Square West, Belfast, commuting from Holywood House, Holywood, County Down, during the summer. His daily routine begins with research, correspondence, or writing for publications for four hours after breakfast. After a two- or three-hour exercise period and dinner, he returns to work for a further two to three hours. He is president of the Belfast Literary Society (1837–39) and also an enthusiastic patron of the visual arts in the city. He enjoys hunting, wildfowling, shooting in Scotland, and gardening, though his health deteriorates from the 1840s.

Early in 1852 Thompson travels to London to make arrangements for that year’s Belfast meeting of the British Association. On February 15 he becomes ill, having suffered a minor stroke. He dies, unmarried, at his Jermyn Street lodgings on the day he is due to return home, February 17, 1852. He is buried in Clifton Street Cemetery, Belfast. He bequeaths his collection to the Belfast Natural History Society, and in March 1852 the Society adds a memorial Thompson Room to its museum, paid for by subscription.

Thompson is a corresponding member of natural history societies in Boston and Philadelphia and has many friends. He is known to assist many other researchers in Ireland, Britain, and the Continent. One of those who thinks highly of his work is Charles Darwin, with whom he corresponds. He also helps many local people, including the poet Francis Davis, with money and practical assistance. He is much loved, and his friends are deeply saddened by his death. His niece, Sydney Mary Thompson, later known by her married surname, Christen, who is born in Belfast, is an amateur naturalist, geologist, and artist, one of the first women to achieve distinction in geology.

(From: “Thompson, William” by Andrew O’Brien and Linde Lunney, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)