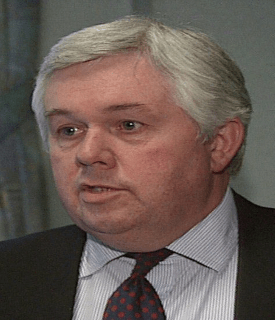

Rory O’Hanlon, former Fianna Fáil politician, is born in Dublin on February 7, 1934. He serves as Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann (2002-07), Leas-Cheann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann (1997-2002), Minister for the Environment (1991-92), Minister for Health (1987-91) and Minister of State for Social Welfare Claims (1982). He serves as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Cavan–Monaghan constituency (1977-2011).

O’Hanlon is brought up in a family that has a strong association with the republican tradition. His father is a member of the Fourth Northern Division of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21). He is educated at Mullaghbawn National School, before later attending St. Mary’s College, Dundalk and Blackrock College in Dublin. He subsequently studies medicine at University College Dublin (UCD) and qualifies as a doctor. In 1965, he is appointed to Carrickmacross as the local general practitioner and is the medical representative on the North Eastern Health Board from its inception in 1970 until 1987.

O’Hanlon enters his first electoral contest when he is the Fianna Fáil candidate in the 1973 Monaghan by-election caused by the election of Erskine Childers to the Presidency. He is unsuccessful on this occasion but is eventually elected at the 1977 Irish general election for the Cavan–Monaghan constituency. He is one of a handful of new Fianna Fáil deputies who are elected in that landslide victory for the party and, as a new TD, he remains on the backbenches. Two years later he becomes a member of Monaghan County Council, serving on that authority until 1987.

In 1979, Jack Lynch suddenly resigns as Taoiseach and Leader of Fianna Fáil. The subsequent leadership election results in a straight contest between Charles Haughey and George Colley. The latter has the backing of the majority of the existing cabinet; however, a backbench revolt sees Haughey become Taoiseach. O’Hanlon supports Colley and is thus overlooked for appointment to the new ministerial and junior ministerial positions. Despite this, he does become a member of the powerful Public Accounts Committee in the Oireachtas.

When Fianna Fáil returns to power after a short-lived Fine Gael–Labour Party government in 1982, O’Hanlon is once again overlooked for ministerial promotion. An extensive cabinet reshuffle toward the end of the year sees him become Minister of State for Social Welfare Claims. His tenure is short-lived as the government falls a few weeks later and Fianna Fáil are out of power.

In early 1983, Charles Haughey announces a new front bench, and O’Hanlon is promoted to the position of spokesperson on Health and Social Welfare.

Following the 1987 Irish general election, Fianna Fáil are back in power, albeit with a minority government, and O’Hanlon becomes Minister for Health. Immediately after taking office, he is confronted with several controversial issues, including the resolution of a radiographers’ dispute and the formation of an HIV/AIDS awareness campaign. While Fianna Fáil campaigns on a platform of not introducing any public spending cuts, the party commits a complete U-turn once in government. The savage cuts about healthcare earn O’Hanlon the nickname “Dr. Death.” Despite earning this reputation, he also introduces a law to curb smoking in public places.

O’Hanlon’s handling of the Department of Health means that he is one of the names tipped for promotion as a result of Ray MacSharry‘s departure as Minister for Finance. In the end, he is retained as Minister for Health and is disappointed not to be given a new portfolio following the 1989 Irish general election.

In 1991, O’Hanlon becomes Minister for the Environment following Albert Reynolds‘ failed leadership challenge against Charles Haughey.

When Reynolds eventually comes to power in 1992, O’Hanlon is one of several high-profile members of the cabinet who lose their ministerial positions.

In 1995, O’Hanlon becomes chair of the Fianna Fáil parliamentary party before being elected Leas-Cheann Comhairle (deputy chair) of Dáil Éireann in 1997. Following the 2002 Irish general election, he becomes Ceann Comhairle of Dáil Éireann. In this position, he is required to remain neutral and, as such, he is no longer classed as a representative of any political party. He is an active chair of the Dáil. However, on occasion, he is criticised, most notably by Labour’s Pat Rabbitte, for allegedly stifling debate and being overly protective of the government. Following the 2007 Irish general election, he is succeeded as Ceann Comhairle by John O’Donoghue. He is the vice-chair of the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Foreign Affairs.

O’Hanlon retires from politics at the 2011 Irish general election.

Two of O’Hanlon’s children have served as local politicians in Cavan-Monaghan. A son Shane is a former member of Monaghan County Council and a daughter Fiona O’Hea serves one term on Cootehill Town Council. The Sinn Féin TD Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin is also a relation of O’Hanlon. He is also the father of actor and comedian Ardal O’Hanlon.