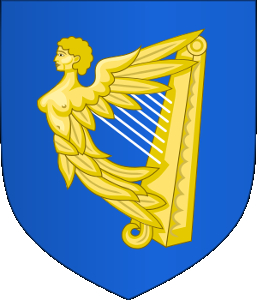

The Union with Ireland Act 1800, which is one of the two complimentary Acts of Union 1800, receives royal assent on July 2, 1800, uniting the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The act means Ireland loses its own independent Parliament and is now to be ruled from England. It will be 1922 before Ireland regains legislative independence.

Two acts are passed in 1800 with the same long title: An Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland. The short title of the act of the British Parliament is Union with Ireland Act 1800, assigned by the Short Titles Act 1896. The short title of the act of the Irish Parliament is Act of Union (Ireland) 1800, assigned by a 1951 act of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, and hence not effective in the Republic of Ireland, where it was referred to by its long title when repealed in 1962.

Before these acts, Ireland has been in personal union with England since 1542, when the Irish Parliament passes the Crown of Ireland Act 1542, proclaiming King Henry VIII of England to be King of Ireland. Since the 12th century, the King of England has been technical overlord of the Lordship of Ireland, a papal possession. Both the Kingdoms of Ireland and England later come into personal union with that of Scotland upon the Union of the Crowns in 1603.

In 1707, the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland are united into a single kingdom: the Kingdom of Great Britain. Upon that union, each House of the Parliament of Ireland passes a congratulatory address to Queen Anne, praying her: “May God put it in your royal heart to add greater strength and lustre to your crown, by a still more comprehensive Union.” The Irish Parliament is both before then subject to certain restrictions that made it subordinate to the Parliament of England and after then, to the Parliament of Great Britain; however, Ireland gains effective legislative independence from Great Britain through the Constitution of 1782.

By this time access to institutional power in Ireland is restricted to a small minority: the Anglo-Irish of the Protestant Ascendancy. Frustration at the lack of reform among the Catholic majority eventually leads, along with other reasons, to a rebellion in 1798, involving a French invasion of Ireland and the seeking of complete independence from Great Britain. This rebellion is crushed with much bloodshed, and the motion for union is motivated at least in part by the belief that the union will alleviate the political rancour that led to the rebellion. The rebellion is felt to have been exacerbated as much by brutally reactionary loyalists as by United Irishmen (anti-unionists).

Furthermore, Catholic emancipation is being discussed in Great Britain, and fears that a newly enfranchised Catholic majority will drastically change the character of the Irish government and parliament also contributes to a desire from London to merge the Parliaments.

According to historian James Stafford, an Enlightenment critique of Empire in Ireland lays the intellectual foundations for the Acts of Union. He writes that Enlightenment thinkers connected “the exclusion of the Irish Kingdom from free participation in imperial and European trade with the exclusion of its Catholic subjects, under the terms of the ‘Penal Laws’, from the benefits of property and political representation.” These critiques are used to justify a parliamentary union between Britain and Ireland.

Complementary acts are enacted by the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland.

The Parliament of Ireland gains a large measure of legislative independence under the Constitution of 1782. Many members of the Irish Parliament jealously guard that autonomy (notably Henry Grattan), and a motion for union is legally rejected in 1799. Only Anglicans are permitted to become members of the Parliament of Ireland though the great majority of the Irish population are Roman Catholic, with many Presbyterians in Ulster. Under the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1793, Roman Catholics regain the right to vote if they own or rent property worth £2 annually. Wealthy Catholics are strongly in favour of union in the hope for rapid religious emancipation and the right to sit as MPs, which only comes to pass under the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829.

From the perspective of Great Britain’s elites, the union is desirable because of the uncertainty that follows the French Revolution of 1789 and the Irish Rebellion of 1798. If Ireland adopts Catholic emancipation willingly or not, a Roman Catholic Parliament could break away from Britain and ally with the French, but the same measure within the United Kingdom would exclude that possibility. Also, in creating a regency during King George III‘s “madness”, the Irish and British Parliaments give the Prince Regent different powers. These considerations lead Great Britain to decide to attempt the merger of both kingdoms and Parliaments.

The final passage of the Act in the Irish House of Commons turns on an about 16% relative majority, garnering 58% of the votes, and similar in the Irish House of Lords, in part per contemporary accounts through bribery with the awarding of peerages and honours to critics to get votes. The first attempt is defeated in the Irish House of Commons by 109 votes to 104, but the second vote in 1800 passes by 158 to 115.