Oliver Joseph St. John Gogarty, Irish poet, author, otolaryngologist, athlete, politician, and well-known conversationalist, is born on August 17, 1878, in Rutland Square, Dublin. He serves as the inspiration for Buck Mulligan in James Joyce‘s novel Ulysses.

In 1887 Gogarty’s father dies of a burst appendix, and he is sent to Mungret College, a boarding school near Limerick. He is unhappy in his new school, and the following year he transfers to Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, England, which he likes little better, later referring to it as “a religious jail.” He returns to Ireland in 1896 and boards at Clongowes Wood College while studying for examinations with the Royal University of Ireland. In 1898 he switches to the medical school at Trinity College, having failed eight of his ten examinations at the Royal.

A serious interest in poetry and literature begins to manifest itself during his years at Trinity. In 1900 he makes the acquaintance of W. B. Yeats and George Moore and begins to frequent Dublin literary circles. In 1904 and 1905 he publishes several short poems in the London publication The Venture and in John Eglinton‘s journal Dana. His name also appears in print as the renegade priest Fr. Oliver Gogarty in George Moore’s 1905 novel The Lake.

In 1905 Gogarty becomes one of the founding members of Arthur Griffith‘s Sinn Féin, a non-violent political movement with a plan for Irish autonomy modelled after the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy.

In July 1907 his first son, Oliver Duane Odysseus Gogarty, is born, and in autumn of that year he leaves for Vienna to finish the practical phase of his medical training. Returning to Dublin in 1908, he secures a post at Richmond Hospital, and shortly afterwards purchases a house in Ely Place opposite George Moore. Three years later, he joins the staff of the Meath Hospital and remains there for the remainder of his medical career.

As a Sinn Féiner during the Irish War of Independence, Gogarty participates in a variety of anti-Black and Tan schemes, allowing his home to be used as a safe house and transporting disguised Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteers in his car. Following the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, he sides with the pro-Treaty government and is made a Free State Senator. He remains a senator until the abolition of the Seanad in 1936, during which time he identifies with none of the existing political parties and votes according to his own whims.

Gogarty maintains close friendships with many of the Dublin literati and continues to write poetry in the midst of his political and professional duties. He also tries his hand at playwriting, producing a slum drama in 1917 under the pseudonym “Alpha and Omega”, and two comedies in 1919 under the pseudonym “Gideon Ouseley,” all three of which are performed at the Abbey Theatre. He devotes less energy to his medical practice and more to his writing during the twenties and thirties.

With the onset of World War II, Gogarty attempts to enlist in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) as a doctor. He is denied on grounds of age. He then departs in September 1939 for an extended lecture tour in the United States, leaving his wife to manage Renvyle House, which has since been rebuilt as a hotel. When his return to Ireland is delayed by the war, he applies for American citizenship and eventually decides to reside permanently in the United States. Though he regularly sends letters, funds, and care-packages to his family and returns home for occasional holiday visits, he never again lives in Ireland for any extended length of time.

Gogarty suffers from heart complaints during the last few years of his life, and in September 1957 he collapses in the street on his way to dinner. He dies on September 22, 1957. His body is flown home to Ireland and buried in Cartron Church, Moyard, near Renvyle.

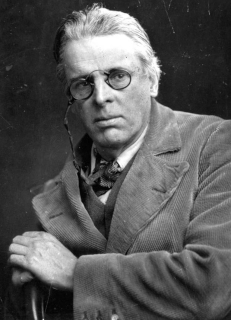

(Pictured: 1911 portrait of Oliver St. John Gogarty painted by Sir William Orpen, currently housed at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland)