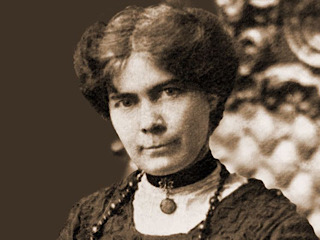

Teresa Brayton, an Irish republican and poet who uses the pen name T. B. Kilbrook, dies in Kilbrook, a small village near Kilcock, County Kildare, on August 19, 1943.

Brayton is born Teresa Coca Boulanger in Kilbrook, the youngest daughter and fifth child of Hugh Boylan and Elizabeth Boylan (née Downes). Her family are long-time nationalists, with her great grandfather previously leading a battalion of pikesmen at the Battle of Prosperous.

Brayton later becomes a notable member of Irish national parties, the United Irish League and Cumann na mBan. She is described as “a patriot, but never in the vulgar sense a politician” in The Irish Times. She is closely associated with leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, and writes poems in honour of Irish patriots including Charles Stewart Parnell, Roger Casement and Patrick Pearse.

Brayton is educated from the age of 5 in Newtown National School. She writes her first poem at the age of twelve, and soon after wins her first literary award. Later on, she trains to be a teacher, and then becomes an assistant teacher to her older sister Elizabeth in the same school she received her education.

Brayton’s father is a tenant farmer, and from a young age she witnesses the effects of the land wars in Ireland. She is a supporter of Parnell, the Irish National Land League and the Irish Home Rule movement. Her work is largely influenced by her family history and Irish nationalism.

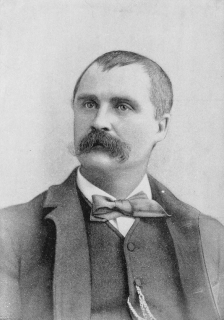

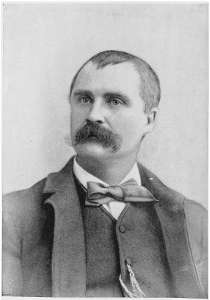

In September 1895, Brayton emigrates to the United States at the age of 27. She first lives in Boston, Chicago, and later moves to New York City. She meets Richard H. Brayton, a French-Canadian who works as an executive in the Municipal Revenue Department, who she then marries. She looks after their home and focuses on her career as a freelance journalist. She lives in the United States for 40 years and becomes well known in Irish American circles as a prominent figure in the Celtic Fellowship. It was in the United States that her reputation is established.

In the 1880s, Brayton begins her career as a poet, writing poetry for both national and provincial Irish newspapers, including Young Ireland and the King’s County Chronicle. She uses the pseudonym “T. B. Kilbrook” while contributing to these papers.

Brayton continues writing under the pseudonym until moving to the United States, where she becomes an acclaimed writer and continues to contribute to papers including the Boston newspaper The Pilot, New York Monitor and Rosary Magazine. Her target audience is the Irish immigrant population of the United States. After establishing herself she releases her poetry in collections including Songs of Dawn (1913) and The Flame of Ireland (1926).

Brayton makes return trips to Ireland regularly and develops a relationship with nationalist peers, and the leaders of the Easter Rising. Upon returning to the United States, she becomes an activist for the Irish Republic and participates in organising the distribution of information to the Irish population through pamphlets and public speaking. Her contribution is acknowledged by Constance Markievicz. Her patriotism to Ireland admit her to the Celtic Fellowship in America, where she shares her poetry at events.

Brayton’s best-known poem is “The Old Bog Road,” which is later set to music by Madeline King O’Farrelly. It has since been recorded and released by many Irish musicians including Finbar Furey, Daniel O’Donnell and Eileen Donaghy, among many others. Many more of her best-known ballads include, The Cuckoo’s Call, By the Old Fireside and Takin’ Tea in Reilly’s.

Brayton makes her permanent return to Ireland at the age of 64 following the death of her husband in 1932 and continues her career as a journalist writing for Irish newspapers and publishes religious poetry in the volume Christmas Verses in 1934. A short story called The New Lodger written by Brayton is published by the Catholic Trust Society in 1933. She dedicates much of her work to the exiled Irish living in the United States, incorporating themes of nostalgia, the familiarity of home and religion throughout her poetry.

Initially upon moving back to Ireland, she lives for a few years with her sister in Bray, County Wicklow. She then moves to Waterloo Avenue, North Strand, County Dublin. Here, she witnesses the bombing of the North Strand on May 31, 1941 during World War II. Shortly after the bombing, she eventually settles back in Kilbrook, where she was born, and lives there for the rest of her life. She spends a brief period of time in the Edenderry Hospital before her death. During her stay there she becomes a good friend with Padraig O’Kennedy, the “Leinster Leader,” who is able to reveal to her something that is linked to a family member of his. A copy of her The Old Bog Road which had been set to music and autographed by her while she was living in the United States. She had it sent to O’Kennedy’s eldest son and on it she wrote the words: “To the boy who sings the Old Bog Road so sweetly.”

Two years after her return to Kilbrook, on August 19, 1943, Brayton dies in the same room where her mother had given birth to her over 75 years previously. She is buried at the Cloncurry cemetery in County Kildare. Her funeral is attended by many, including the then Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera.

From the vivid imagery she speaks of in her poetry, Brayton, both a poet and a novelist, is described by some as “the poet of the homes of Ireland.” Such scenes include the vivid imagery of the fireside chats, the sound of her latch lifting as neighbours in to visit at night from her poem “The Old Boreen” and about her home cooking and work from “When the Leaves Begin to Fall.” Such images can be compared to most Irish households and can depict a vivid picture to those reading her poetry.

Brayton’s poetry leaves a lasting sense of Irish beauty and community. This can be seen in such poems as “A Christmas Blessing” where she speaks of “taking and giving in friendship” during Christmas. Since her passing she has continued to keep an audience from overseas from Boston and New York primarily, this as a result of the reminder her poems give to Irish exiles of Irish traditions and music which was close to them. While her poems are more often serious, some portray an almost comical undertone tone. In an article in The Irish Times, her poetry is also said to have a racy feel to them.