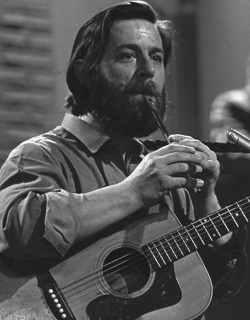

Ciarán Bourke, Irish musician and one of the founding members of the Irish folk band The Dubliners, is born in Dublin on February 18, 1935.

Although born in Dublin, Bourke lives most of his life in Tibradden, County Dublin. His father, a doctor, is in practice in the city. The children have an Irish-speaking nanny. His early exposure to Irish continues throughout his education, attending Colaiste Mhuire, Parnell Square, Dublin. He later attends University College Dublin for a course in Agricultural Science. He does not take his degree but always retains an interest in farming.

After leaving university Bourke meets two of his future bandmates in The Dubliners, Ronnie Drew and Barney McKenna, who invite him to join their sessions in O’Donoghue’s Pub where he plays tin whistle, mouth organ and guitar, and sings. Luke Kelly, who had been singing around the clubs in England, returns to Dublin and joins them, with the four gaining local popularity. Taking the name The Dubliners, the group puts together the first folk concert of its kind in Dublin. The concert is a success, then a theatrical production called “A Ballad Tour of Ireland” is staged at the Gate Theatre shortly afterwards. In 1964 fiddle player John Sheahan joins the band and this becomes known as the original Dubliners line-up.

Bourke is responsible for bringing a Gaelic element to The Dubliners’ music with songs such as “Peggy Lettermore” and “Sé Fáth Mo Bhuartha” being performed in the Irish language. He also sings a number of the group’s more lighthearted and humorous numbers such as “Jar of Porter,” “The Dublin Fusiliers,” “The Limerick Rake,” “Mrs. McGrath,” “Darby O’Leary,” “All For Me Grog” and “The Ballad of Ronnie’s Mare,” as well as patriotic songs such as “Roddy McCorley,” “The Enniskillen Dragoons,” “Take It Down From The Mast” and “Henry Joy.”

On April 5, 1974 The Dubliners travel to Eastbourne where they are to appear in concert. Kelly is worried by the way Bourke keeps moving his head about, as if trying to alleviate increasing pain. Four minutes into the second half, it is decided he cannot continue with the show. Kelly insists that a doctor should be phoned and instructs to await their return to the Irish Club at Eaton Square. The roadie for the trip, John Corry, thinks that it is better to drive straight to St. George’s Hospital in London, where the doctors diagnose a brain aneurysm. He is transferred to the Atkinson Morley Hospital in Wimbledon, while doctors wait for his wife to return from a trip to Ghana, to get her signature before operating. She is told that there is danger of further haemorrhaging. He is operated on at the earliest opportunity. The bleeding begins again while he is on the table which means that they cannot repair the damage, only staunch the bleeding. This leaves him paralysed down his left side and confused as to where he is and what has happened.

Bourke receives intensive therapy, attending a clinic in Dún Laoghaire, County Dublin. He is heartened by his progress and insists on rejoining The Dubliners on their next tour of the Continent in November that year.

Bourke’s continued insistence that he is fit enough to join them on the forthcoming German tour causes them considerable disquiet. They prefer he ease himself back to work, with a few small shows in Ireland. The tour gradually begins to take its toll on him, and it is decided that for the sake of his health he should return home. He flies from Brussels to Dublin.

Bourke makes his last public appearance on Ireland’s RTÉ One during The Late Late Show‘s tribute to The Dubliners in 1987. Despite his lingering paralysis he recites “The Lament for Brendan Behan” after which everyone in the studio, led by Ronnie Drew, sing “The Auld Triangle.”

Bourke dies on May 10, 1988, after a long illness. From 1974 until his death, he is continued to be paid by the band. A fifth member of the group is not recruited until after his death.