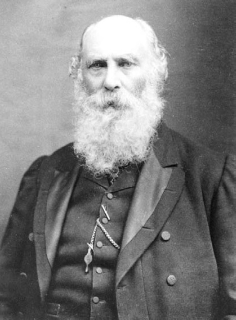

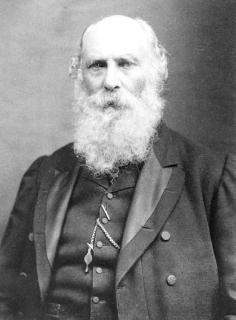

George Johnstone Stoney FRS, Irish physicist, is born on February 15, 1826, at Oakley Park, near Birr, County Offaly, in the Irish Midlands. He is most famous for introducing the term “electron” as the “fundamental unit quantity of electricity.” He introduces the concept, though not the word, as early as 1874, initially naming it “electrine,” and the word itself comes in 1891. He publishes around 75 scientific papers during his lifetime.

Stoney is the son of George Stoney and Anne (née Bindon Blood). His only brother is Bindon Blood Stoney, who becomes chief engineer of the Dublin Port and Docks Board. The Stoney family is an old-established Anglo-Irish family. During the time of the famine (1845–52), when land prices plummet, the family property is sold to support his widowed mother and family. He attends Trinity College Dublin (TCD), graduating with a BA degree in 1848. From 1848 to 1852 he works as an astronomy assistant to William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse, at Birr Castle, County Offaly, where Parsons had built the world’s largest telescope, the 72-inch Leviathan of Parsonstown. Simultaneously he continues to study physics and mathematics and is awarded an MA by TCD in 1852.

From 1852 to 1857, Stoney is professor of physics at Queen’s College Galway. From 1857 to 1882, he is employed as Secretary of the Queen’s University of Ireland, an administrative job based in Dublin. In the early 1880s, he moves to the post of superintendent of Civil Service Examinations in Ireland, a post he holds until his retirement in 1893. He continues his independent scientific research throughout his decades of non-scientific employment duties in Dublin. He also serves for decades as honorary secretary and then vice-president of the Royal Dublin Society (RDS), a scientific society modeled after the Royal Society of London and, after his move to London in 1893, he serves on the council of that society as well. Additionally, he intermittently serves on scientific review committees of the British Association for the Advancement of Science from the early 1860s.

Stoney publishes seventy-five scientific papers in a variety of journals, but chiefly in the journals of the Royal Dublin Society. He makes significant contributions to cosmic physics and to the theory of gases. He estimates the number of molecules in a cubic millimeter of gas, at room temperature and pressure, from data obtained from the kinetic theory of gases. His most important scientific work is the conception and calculation of the magnitude of the “atom of electricity.” In 1891, he proposes the term “electron” to describe the fundamental unit of electrical charge, and his contributions to research in this area lays the foundations for the eventual discovery of the particle by J. J. Thomson in 1897.

Stoney’s scientific work is carried out in his spare time. A heliostat he designed is in the Science Museum Group collection. He is elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in June 1861.

Stoney proposes the first system of natural units in 1881. He realizes that a fixed amount of charge is transferred per chemical bond affected during electrolysis, the elementary charge e, which can serve as a unit of charge, and that combined with other known universal constants, namely the speed of light c and the Newtonian constant of gravitation G, a complete system of units can be derived. He shows how to derive units of mass, length, time and electric charge as base units. Due to the form in which Coulomb’s law is expressed, the constant 4πε0 is implicitly included, ε0 being the vacuum permittivity.

Like Stoney, Max Planck independently derives a system of natural units (of similar scale) some decades after him, using different constants of nature.

Hermann Weyl makes a notable attempt to construct a unified theory by associating a gravitational unit of charge with the Stoney length. Weyl’s theory leads to significant mathematical innovations, but his theory is generally thought to lack physical significance.

Stoney marries his cousin, Margaret Sophia Stoney, by whom he has had two sons and three daughters. One of his sons, George Gerald Stoney FRS, is a scientist. His daughter Florence Stoney OBE is a radiologist while his daughter Edith is considered to be the first woman medical physicist. His most scientifically notable relative is his nephew, the Dublin-based physicist George Francis FitzGerald. He is second cousin of the grandfather of Ethel Sara Turing, mother of Alan Turing.

After moving to London, Stoney lives first at Hornsey Rise, north London, before moving to 30 Chepstow Crescent, Notting Hill, West London. In his later years illness confines him to a single floor of the house, which is filled with books, papers, and scientific instruments, often self-made. He dies at his home in Notting Hill, on July 5, 1911. His cremated ashes are buried in St. Nahi’s Church, Dundrum, Dublin.

Stoney receives an honorary Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) from the University of Dublin in June 1902. Also in 1902, he is elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society. The street that he lived on in Dundrum is later renamed Stoney Road in his memory.