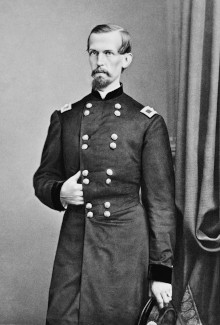

Edward Hand, Irish soldier, physician, and politician who serves in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, is born in Clyduff, King’s County (now County Offaly) on December 31, 1744. He rises to the rank of general and later is a member of several Pennsylvania governmental bodies.

Hand, the son of John Hand, is baptised in Shinrone. Among his immediate neighbours are the Kearney family, ancestors of United States President Barack Obama. He is a descendant of either the families of Mag Fhlaithimh (of south Ulaidh and Mide) or Ó Flaithimhín (of the Síol Muireadaigh) who, through mistranslation became Lavin or Hand.

Hand earns a medical certificate from Trinity College, Dublin. In 1767, he enlists as a Surgeon’s Mate in the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot. On May 20, 1767, he sails with the regiment from Cobh, County Cork, arriving at Philadelphia on July 11, 1767. In 1772, he is commissioned an ensign. He marches with the regiment to Fort Pitt, on the forks of the Ohio River, returning to Philadelphia in 1774, where he resigns his commission.

In 1774, Hand moves to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he practices medicine. On March 13, 1775, he marries Catherine Ewing. Lancaster is the region of some of the earliest Irish and Scotch-Irish settlements in Pennsylvania. As a people, they are well known for their anti-English and revolutionary convictions. He is active in forming the Lancaster County Associators, a colonial militia. He is a 32nd degree Freemason, belonging to the Montgomery Military Lodge number 14.

Hand enters the Continental Army in 1775 as a lieutenant colonel in the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment under Colonel William Thompson. He is promoted to colonel in 1776 and placed in command of the 1st Continental, then designated the 1st Pennsylvania. Promoted to brigadier general in March 1777, he serves as the commander of Fort Pitt, fighting British loyalists and their Indian allies. He is recalled, after over two years at Fort Pitt, to serve as a brigade commander in Major General La Fayette‘s division.

In 1778, Hand attacks the Lenape, killing Captain Pipe‘s mother, brother, and a few of his children during a military campaign. Failing to distinguish among the Native American groups, he had attacked the neutral Lenape while trying to reduce the Indian threat to settlers in the Ohio Country, because other tribes, such as the Shawnee, had allied with the British.

After a few months, he is appointed Adjutant General of the Continental Army and serves during the Siege of Yorktown in that capacity. In recognition of his long and distinguished service, he is promoted by brevet to major general in September 1783. He resigns from the Army in November 1783.

Hand returns to Lancaster and resumes the practice of medicine. A Federalist, he is also active in civil affairs. Beginning in 1785, he owns and operates Rock Ford plantation, a 177-acre farm on the banks of the Conestoga River, one mile south of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The Georgian brick mansion remains today, and the farm is a historic site open to the public.

Hand dies from typhoid fever, dysentery or pneumonia at Rock Ford on September 3, 1802, although medical records are unclear with some sources stating he died of cholera. There is no evidence Lancaster County suffered from a cholera epidemic in 1802. He is buried in St. James’s Episcopal Cemetery in Lancaster, the same church where he had served as a deacon.