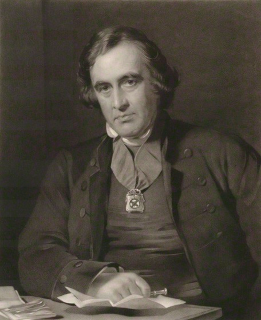

Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings, Anglo-Irish politician and military officer, is born on December 9, 1754, at Moira, County Down. As Governor-General of India, he conquers the Maratha states and greatly strengthens British rule in India.

Rawdon-Hastings is the son of John Rawdon, 1st Earl of Moira, and Elizabeth Hastings, 13th Baroness Hastings, who is a daughter of Theophilus Hastings, 9th Earl of Huntingdon. He is baptised at St. Audoen’s Church, Dublin, on January 2, 1755. He grows up in Moira and in Dublin. He attends Harrow School and matriculates at University College, Oxford, but drops out. While there, he becomes friends with Banastre Tarleton.

He joins the British Army on August 7, 1771, as an ensign in the 15th Regiment of Foot. With his uncle Francis Hastings, 10th Earl of Huntingdon, he goes on the Grand Tour. On October 20, 1773, he is promoted to lieutenant in the 5th Regiment of Foot. He returns to England to join his regiment, and sails for America on May 7, 1774.

He serves in the American Revolutionary War (1775–81), first seeing action at the Battles of Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Bunker Hill. He is rewarded with an English peerage in 1783. He succeeds his father as Earl of Moira in 1793. When the Whigs come to power in 1806, he is appointed Master-General of the Ordnance, a post he resigns on the fall of his party in 1807. Taking an active part in the business of the House of Lords, he belongs to the circle of the Prince of Wales (later George IV), through whose influence he is appointed Governor-General of India, on November 11, 1812. He lands at Calcutta (Kolkata) and assumes office in October 1813. Facing an empty treasury, he raises a loan in Lucknow from the nawab-vizier there and defeats the Gurkhas of Nepal in 1816. They abandon disputed districts, cede some territory to the British, and agree to receive a British resident (administrator). For this success, in 1817 he is raised to the rank of Marquess of Hastings together with the subsidiary titles Viscount Loudoun and Earl of Rawdon.

He then has to deal with a combination of Maratha powers in western India whose Pindaris, bands of horsemen attached to the Maratha chiefs, are ravaging British territory in the Northern Sarkars, in east-central India. In 1817, he offers the Marathas the choice of cooperation with the British against the Pindaris or war. The Peshwa, the Prime Minister of the Maratha Confederacy, the raja of Nagpur, and the army under Holkar II, ruler of Indore, chose war and are defeated. The Pindari bands are broken up, and, in a settlement, the Peshwa’s territories are annexed, and the Rajput princes accept British supremacy. By 1818 these developments establish British sovereignty over the whole of India east of the Sutlej River and Sindh. Rawdon-Hastings also suppresses pirate activities off the west coast of India and in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. In 1819, Sir Stamford Raffles, under his authority, obtains the cession by purchase of the strategic island of Singapore.

In internal affairs, Rawdon-Hastings begins the repair of the Mughal canal system and brings the pure water of the Yamuna River (Jumna) into Delhi, encourages education in Bengal, begins a process of Indianization by raising the status and powers of subordinate Indian judges, and takes the first measures for the revenue settlement of the extensive “conquered and ceded” provinces of the northwest.

Rawdon-Hastings’s competent administration, however, ends under a cloud because of his indulgence to a banking house. Though he is cleared of any corrupt motive, the home authorities censure him. He resigns and returns to England in 1823, receiving the comparatively minor post of Governor of Malta in 1824. He dies at sea off Naples on November 28, 1826, aboard HMS Revenge, while attempting to return home with his wife. She returns his body to Malta, and following his earlier directions, cuts off his right hand and preserves it, to be buried with her when she dies. His body is then laid to rest in a large marble sarcophagus in Hastings Gardens, Valletta. His hand is eventually interred, clasped with hers, in the family vault at Loudoun Kirk.

In 1828, two years after Rawdon-Hastings’s death, members of the India House, to make some amends for their vote of censure, give £20,000 to trustees for the benefit of Hastings’s son.

(Pictured: “Portrait of Francis Rawdon, 2nd Earl of Moira, later 1st Marquess of Hastings (1754 – 1826)” possibly by Martin Archer Shee, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Ireland)