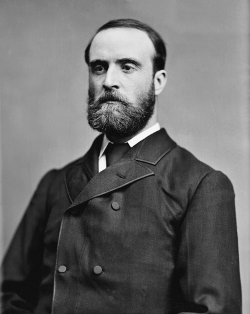

James “Jemmy” Hope, Society of United Irishmen leader who fights in the Irish Rebellions of 1798 and 1803 against British rule in Ireland, is born in Templepatrick, County Antrim on August 25, 1764.

Hope is born to a Presbyterian family originally of Covenanter stock. He is apprenticed as a linen weaver but attends night school in his spare time. Influenced by the American Revolution, he joins the Irish Volunteers, but upon the demise of that organisation and further influenced by the French Revolution, he joins the Society of the United Irishmen in 1795.

Hope quickly establishes himself as a prominent organiser and is elected to the central committee in Belfast, becoming close to leaders such as Samuel Neilson, Thomas Russell, and Henry Joy McCracken. He is almost alone among the United Irish leaders in targeting manufacturers as well as landowners as the enemies of all radicals. In 1796, he is sent to Dublin to assist the United Irish organisation there to mobilise support among the working classes, and he is successful in establishing several branches throughout the city and especially in The Liberties area. He also travels to counties in Ulster and Connacht, disseminating literature and organizing localities.

Upon the outbreak of the 1798 rebellion in Leinster, Hope is sent on a failed mission to Belfast by Henry Joy McCracken to brief the leader of the County Down United Irishmen, Rev. William Steel Dickson, with news of the planned rising in County Antrim, unaware that Dickson had been arrested only a couple of days before. He manages to escape from Belfast in time to take part in the Battle of Antrim where he plays a skillful and courageous role with his “Spartan Band,” in covering the retreat of the fleeing rebels after their defeat.

Hope manages to rejoin McCracken and his remaining forces after the battle at their camp upon Slemish mountain, but the camp gradually disperses, and the dwindling band of insurgents are then forced to go on the run. He successfully eludes capture, but his friend McCracken is captured and executed on July 17. Upon the collapse of the general rising, he refuses to avail of the terms of an amnesty offered by Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis on the grounds that to do so would be “not only a recantation of one’s principles, but a tacit acquiescence in the justice of the punishment which had been inflicted on thousands of my unfortunate associates.”

Hope lives the years following 1798 on the move between counties Dublin, Meath and Westmeath but is finally forced to flee Dublin following the failure of Robert Emmet‘s rebellion in 1803. He returns to the north and evades the authorities attentions in the ensuing repression by securing employment with a sympathetic friend from England. He is today regarded as the most egalitarian and socialist of all the United Irish leadership.

James Hope dies in 1846 and is buried in the Mallusk cemetery, Newtownabbey. His gravestone features the outline of a large dog, which supposedly brought provisions to him and his compatriots when they were hiding following the Battle of Antrim.