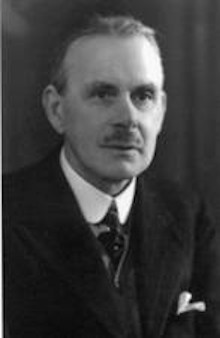

John Miller Andrews, the second Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, resigns on April 28, 1943 and is succeeded by Sir Basil Brooke, later Lord Brookeborough.

Andrews is born in Comber, County Down, on July 17, 1871, the eldest child in the family of four sons and one daughter of Thomas Andrews, flax spinner, and his wife Eliza Pirrie, a sister of William Pirrie, 1st Viscount Pirrie, chairman of Harland & Wolff. He is named after his maternal great-uncle, John Miller of Comber (1795–1883). As a young man, with his parents and family, he is a committed and active member of the Non-subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland. He regularly attends Sunday worship in the church built on land donated by his great-grandfather James Andrews in his home town Comber.

Andrews is educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution. In business, he is a landowner, a director of his family linen-bleaching company and of the Belfast Ropeworks. His younger brother, Thomas Andrews, who dies in the 1912 sinking of the RMS Titanic, is managing director of the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast. Another brother, Sir James Andrews, 1st Baronet, is Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland.

In 1902 Andrews marries Jessie Ormrod, eldest daughter of Bolton stockbroker Joseph Ormrod at Rivington Unitarian Chapel, Rivington, near Chorley, Lancashire, England. They have one son and two daughters. His younger brother, Sir James, marries Jessie’s sister.

Andrews is elected as a member of parliament in the House of Commons of Northern Ireland, sitting from 1921 until 1953 (for Down from 1921–1929 and for Mid Down from 1929–1953). He is a founder member of the Ulster Unionist Labour Association, which he chairs, and is Minister of Labour from 1921 to 1937. He is Minister of Finance from 1937 to 1940, succeeding to the position on the death of Hugh MacDowell Pollock. On the death of James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon, in 1940, he becomes leader of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the second Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

In April 1943 backbench dissent forces him from office. He is replaced as Prime Minister by Sir Basil Brooke. Andrews remains, however, the recognised leader of the UUP for three more years. Five years later he becomes the Grand Master of the Orange Order. Throughout his life he is deeply involved in the Orange Order. He holds the positions of Grand Master of County Down from 1941 and Grand Master of Ireland (1948–1954). In 1949 he is appointed Imperial Grand Master of the Grand Orange Council of the World.

From 1949, he is the last parliamentary survivor of the original 1921 Northern Ireland Parliament, and as such is recognised as the Father of the House. He is the only Prime Minister of Northern Ireland not to have been granted a peerage. His predecessor and successor received hereditary viscountcies, and later prime ministers are granted life peerages.

Andrews serves on the Comber Congregational Committee from 1896 until his death, holding the position of Chairman from 1935 onward. He dies in Comber on August 5, 1956 and is buried in the small graveyard adjoining the Non-subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland.

Captain

Captain