Billy “King Rat” Wright, prominent Ulster loyalist death squad leader during the ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles, is murdered on December 27, 1997, in HM Prison Maze by three members of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) who manage to smuggle guns into the prison.

William Stephen “Billy” Wright, named after his grandfather, is born in Wolverhampton, England on July 7, 1960, to David Wright and Sarah McKinley, Ulster Protestants from Portadown, Northern Ireland. The family returns to Northern Ireland in 1964. While attending Markethill High School, Wright takes a part-time job as a farm labourer where he comes into contact with a number of staunchly unionist and loyalist farmers who serve with the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Reserve or the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). The conflict known as the Troubles has been raging across Northern Ireland for about five years by this stage, and many young men such as Wright are swept up in the maelstrom of violence as the Provisional Irish Republican Army ramps up its bombing campaign and sectarian killings of Catholics by loyalists continue to escalate. During this time his opinions move towards loyalism and soon he gets into trouble for writing the initials “UVF” on a local Catholic primary school wall. When he refuses to clean off the vandalism, he is transferred from the area and sent to live with an aunt in Portadown.

Wright joins the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) in 1975. After spending several years in prison and becoming a born-again Christian, he resumes his UVF activities and becomes commander of its Mid-Ulster Brigade in the early 1990s, taking over from Robin “the Jackal” Jackson. According to the Royal Ulster Constabulary, he is involved in the sectarian killings of up to 20 Catholics, although he is never convicted for any. It is alleged that Wright, like his predecessor, is an agent of the RUC Special Branch.

Wright attracts considerable media attention during the Drumcree standoff, when he supports the Protestant Orange Order‘s desire to march its traditional route through the Catholic/Irish nationalist area of his hometown of Portadown. In 1994, the UVF and other paramilitary groups call ceasefires. However, in July 1996, Wright’s unit breaks the ceasefire and carries out a number of attacks, including a sectarian killing. For this, Wright and his Portadown unit of the Mid-Ulster Brigade are stood down by the UVF leadership. He is expelled from the UVF and threatened with execution if he does not leave Northern Ireland. He ignores the threats and, along with many of his followers, defiantly forms the breakaway Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF), becoming its leader.

The LVF carries out a string of killings of Catholic civilians. In March 1997 Wright is sent to the HM Prison Maze for having threatened the life of a woman. While imprisoned, Wright continues to direct the LVF’s activities. On the morning of December 27, 1997, he is assassinated inside the prison by three INLA volunteers – Christopher “Crip” McWilliams, John “Sonny” Glennon and John Kennaway – armed with two smuggled pistols, a FEG PA-63 semi-automatic and a .22 Derringer. The LVF carries out a wave of sectarian attacks in retaliation. There is speculation that the authorities collude in his killing as he is a threat to the peace process. An inquiry finds no evidence of this but concludes there are serious failings by the prison authorities.

Owing to his uncompromising stance as an upholder of Ulster loyalism and opposition to the Northern Ireland peace process, Wright is regarded as a cult hero, icon, and martyr by hardline loyalists. His image adorns murals in loyalist housing estates and many of his devotees have tattoos bearing his likeness. His death is greeted with relief and no little satisfaction, however, from the Irish nationalist community.

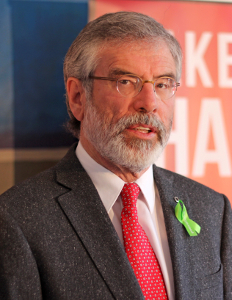

Former

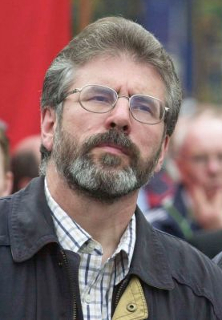

Former