Michael William Balfe, Irish composer best remembered for his opera The Bohemian Girl, dies in Dublin on October 20, 1870.

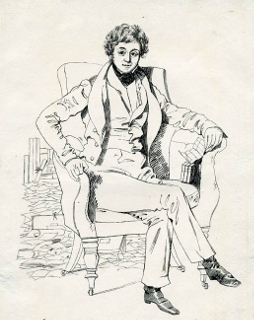

Balfe is born in Dublin on May 15, 1808, where his musical gifts become apparent at an early age. He receives instruction from his father, a dancing master and violinist, and the composer William Rooke. His family moves to Wexford when he is a child.

In 1817, Balfe appears as a violinist in public, and in this year composes a ballad, first called “Young Fanny” and afterwards, when sung in Paul Pry by Lucia Elizabeth Vestris, “The Lovers’ Mistake”. In 1823, upon the death of his father, he moves to London and is engaged as a violinist in the orchestra of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. He eventually becomes the leader of that orchestra. While there, he studies violin with Charles Edward Horn and composition with Charles Frederick Horn.

While still playing the violin, Balfe pursues a career as an opera singer. He debuts unsuccessfully at Norwich in Carl Maria von Weber‘s Der Freischütz. In 1825, Count Mazzara takes him to Rome for vocal and musical studies and introduces him to Luigi Cherubini. In Italy, he also pursues composing, writing his first dramatic work, a ballet, La Perouse. He becomes a protégée of Gioachino Rossini‘s, and at the close of 1827, he appears as Figaro in The Barber of Seville at the Italian opera in Paris.

Balfe soon returns to Italy, where he is based for the next eight years, singing and composing several operas. In 1829 in Bologna, he composes his first cantata for the soprano Giulia Grisi, then 18 years old. He produces his first complete opera, I rivali di se stessi, at Palermo in the carnival season of 1829—1830.

Balfe returned to London in May 1835. His initial success takes place some months later with the premiere of The Siege of Rochelle on October 29, 1835, at Drury Lane. Encouraged by his success, he produces The Maid of Artois in 1836, which is followed by more operas in English. In July 1838, Balfe composes a new opera, Falstaff, for The Italian Opera House, based on The Merry Wives of Windsor, with an Italian libretto by S. Manfredo Maggione.

In 1841, Balfe founds the National Opera at the Lyceum Theatre, but the venture is a failure. The same year, he premieres his opera, Keolanthe. He then moves to Paris, presenting Le Puits d’amour in early 1843, followed by his opera based on Les quatre fils Aymon for the Opéra-Comique and L’étoile de Seville for the Paris Opera. Meanwhile, in 1843, he returns to London where he produces his most successful work, The Bohemian Girl, on November 27, 1843, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The piece runs for over 100 nights, and productions are soon mounted in New York, Dublin, Philadelphia, Vienna, Sydney, and throughout Europe and elsewhere.

From 1846 to 1852, Balfe is appointed musical director and principal conductor for the Italian Opera at Her Majesty’s Theatre. There he first produces several of Giuseppe Verdi‘s operas for London audiences. He conducts for Jenny Lind at her opera debut and on many occasions thereafter.

In 1851, in anticipation of The Great Exhibition in London, Balfe composes an innovative cantata, Inno Delle Nazioni, sung by nine female singers, each representing a country. He continues to compose new operas in English, including The Armourer of Nantes (1863), and writes hundreds of songs. His last opera, nearly completed when he dies, is The Knight of the Leopard and achieves considerable success in Italian as Il Talismano.

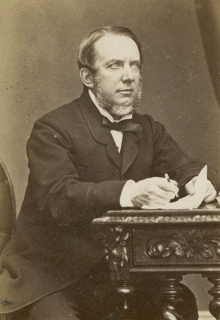

Balfe retires in 1864 to Hertfordshire, where he rents a country estate. He dies at his home in Rowney Abbey, Ware, Hertfordshire, on October 20, 1870, and is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery in London, next to fellow Irish composer William Vincent Wallace. In 1882, a medallion portrait of him is unveiled in Westminster Abbey.

In all, Balfe composes at least 29 operas. He also writes several cantatas and a symphony. His only large-scale piece that is still performed regularly today is The Bohemian Girl.