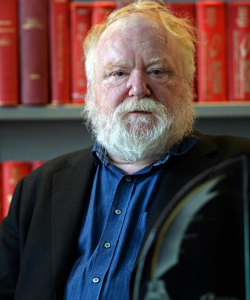

Pádraig de Brún, also called Patrick Joseph Monsignor Browne, a Roman Catholic priest, linguist, Classicist, and Celticist, is born in Grangemockler, County Tipperary, on October 13, 1889. With regard to his contribution to modern literature in Irish, he, who Louis de Paor terms in 2014 “one of the most distinguished literary figures of his time,” is also a writer of Irish poetry in the Irish language and the literary translator of many of the greatest works of the Western canon into Modern Irish. He serves as President of University College, Galway (UCG), and is known in friendly and informal circles as Paddy Browne.

De Brún is the son of a primary school teacher, Maurice Browne. He is educated locally, at Rockwell College, Cashel, and at Holy Cross College, Drumcondra, Dublin (at both he is tutored in mathematics by Éamon de Valera). In 1909, he is awarded a BA from the Royal University of Ireland. He is awarded an MA degree by the National University of Ireland, and wins a traveling scholarship in mathematics and mathematical physics, enabling him to pursue further studies in Paris. He is ordained as a Catholic priest at the Irish College in Paris in 1913, the same year he earns his D.Sc. in mathematics from the University of Paris under Émile Picard.

After a period at the University of Göttingen, de Brún is appointed professor of mathematics at St. Patrick’s Pontifical University, Maynooth, in 1914. In April 1945, he is elected by the Senate of the National University of Ireland to succeed John Hynes as President of University College, Galway, an office he holds until his retirement in 1959. His friend Thomas MacGreevy refers to de Brún as, “Rector Magnificus,” and praises his, “Olympian capacity to appreciate the most exalted works of art and literature, ancient and modern.”

The School of Mathematics, Mathematical Physics and Statistics is based in Áras de Brún, a building named in de Brún‘s honour. He subsequently becomes Chairman of the Arts Council of Ireland, a position he holds until his death in 1960. He also serves as chairman of the Council of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS).

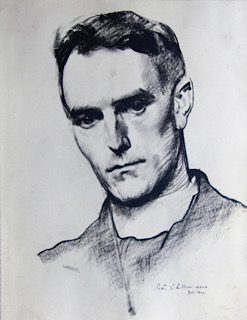

De Brún is close friend of 1916 Easter Rising leader Seán Mac Diarmada and is deeply affected by the latter’s execution.

De Brún was a prolific writer of Irish poetry in the Irish language, including the well-known poem “Tháinig Long ó Valparaiso.” He further translates into Modern Irish many great works of the Western canon, including Homer‘s Iliad and Odyssey, Sophocles‘ Antigone and Oedipus Rex, and Plutarch‘s Parallel Lives, as well as French stage plays by Jean Racine and Dante Alighieri‘s Divine Comedy. With regards to his importance to modern literature in Irish, he is recently termed “one of the most distinguished literary figures of his time.”

The French Government awards de Brún the title of Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur in 1949, and in 1956, the order Al Merito della Repubblica Italiana is conferred on him by the President of Italy. He is created a Domestic Prelate (a Monsignor) by Pope Pius XII in 1950.

De Brún purchases land at Dunquin in the Dingle Peninsula Gaeltacht. In the 1920s, he also builds a house there known as Tigh na Cille, where his sister and her children often visit and stay at length. Through his literary mentorship of his niece, the future poet Máire Mhac an tSaoi, he has been credited with having an enormous influence upon the future development of modern literature in Irish.

After suffering a heart attack at his house at Seapoint, Dún Laoghaire, into which he had recently moved, de Brún dies on June 5, 1960, in St. Vincent’s nursing home, Leeson Street, Dublin.