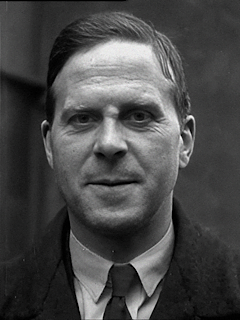

James Ryan, medical doctor, revolutionary and politician who serves in every Fianna Fáil government from 1932 to 1965, dies on his farm at Kindlestown, County Wicklow, on September 25, 1970.

Ryan is born on the family farm at Tomcoole, near Taghmon, County Wexford, on December 6, 1892. The second-youngest of twelve children, he is educated at St. Peter’s College, Wexford, and Ring College, Waterford. In 1911, he wins a county council scholarship to University College Dublin (UCD) where he studies medicine.

In March 1917, Ryan passes his final medical examinations. That June he sets up medical practice in Wexford. In 1921, he moves to Dublin where he opens a doctor’s practice at Harcourt Street, specialising in skin diseases at the Skin and Cancer Hospital on Holles Street. He leaves medicine in 1925, after he purchases Kindlestown, a large farm near Delgany, County Wicklow. He lives there and it remains a working farm until his death.

In July 1919, Ryan marries Máirín Cregan, originally from County Kerry and a close friend of Sinéad de Valera throughout her life. Cregan, like her husband, also fought in the Easter Rising and is subsequently an author of children’s stories in Irish. They have three children together.

One of Ryan’s sisters, Mary Kate, marries Seán T. O’Kelly, one of Ryan’s future cabinet colleagues and a future President of Ireland. Following her death O’Kelly marries her sister, Phyllis Ryan. Another of Ryan’s sisters, Josephine (‘Min’) Ryan, marries Richard Mulcahy, a future leader of Fine Gael. Another sister, Agnes, marries Denis McCullough, a Cumann na nGaedheal TD from 1924 to 1927. He is also the great-grandfather of Ireland and Leinster Rugby player James Ryan.

While studying at university in 1913, Ryan joins the Gaelic League at Clonmel. The company commander recruits the young Catholic nationalist, who becomes a founder-member of the Irish Volunteers and is sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) the following year. In 1916, he goes first to Cork to deliver a message from Seán Mac Diarmada to Tomás Mac Curtain that the Easter Rising is due to happen on Easter Sunday, then to Cork again in a 12-hour journey in a car to deliver Eoin MacNeill‘s cancellation order, which attempts to stop the rising. When he arrives back on Tuesday, he serves as the medical officer in the General Post Office (GPO) and treats many wounds, including James Connolly‘s shattered ankle, a wound which gradually turns gangrenous. He is, along with Connolly, one of the last people to leave the GPO when the evacuation takes place. Following the surrender of the garrison, he is deported to HM Prison Stafford in England and subsequently Frongoch internment camp. He is released in August 1916.

Ryan rejoins the Volunteers immediately after his release from prison, and in June 1917, he is elected Commandant of the Wexford Battalion. His political career begins the following year when he is elected as a Sinn Féin candidate for the constituency of South Wexford in the 1918 United Kingdom general election in Ireland. Like his fellow Sinn Féin MPs, he refuses to attend the Westminster Parliament. Instead he attends the proceedings of the First Dáil on January 21, 1919. As the Irish War of Independence goes on, he becomes Brigade Commandant of South Wexford and is also elected to Wexford County Council, serving as chairman on one occasion. In September 1919, he is arrested by the British and interned on Spike Island and later Bere Island. In February 1921, he is imprisoned at Kilworth Internment Camp, County Cork. He is later moved on Ballykinlar Barracks in County Down and released in August 1921.

In the 1922 Irish general election, Ryan and one of the other two anti-Treaty Wexford TDs lose their seats to pro-Treaty candidates. During the Irish Civil War, he is arrested and held in Mountjoy Prison before being transferred to Curragh Camp, where he embarks on a 36-day hunger strike. While interned he wins back his Dáil seat as an abstentionist at the 1923 Irish general election. He is released from prison in December 1923.

In 1926, Ryan is among the Sinn Féin TDs who follow leader Éamon de Valera out of the party to found Fianna Fáil. They enter the Dáil in 1927 and spend five years on the opposition benches.

Following the 1932 Irish general election, Fianna Fáil comes to office and Ryan is appointed Minister for Agriculture, a position he continuously holds for fifteen years. He faces severe criticism over the Anglo-Irish trade war with Britain as serious harm is done to the cattle trade, Ireland’s main export earner. The trade war ends in 1938 with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement between both governments, after a series of talks in London between the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, de Valera, Ryan and Seán Lemass.

In 1947, after spending fifteen years as Minister for Agriculture, Ryan is appointed to the newly created positions of Minister for Health and Minister for Social Welfare. Following Fianna Fáil’s return to power at the 1951 Irish general election, he returns as Minister for Health and Social Welfare. Following the 1954 Irish general election, Fianna Fáil loses power and he moves to the backbenches once again.

Following the 1957 Irish general election, Fianna Fáil are back in office and de Valera’s cabinet has a new look to it. In a clear message that there will be a change to economic policy, Ryan, a close ally of Seán Lemass, is appointed Minister for Finance, replacing the conservative Seán MacEntee. The first sign of a new economic approach comes in 1958, when Ryan brings the First Programme for Economic Development to the cabinet table. This plan, the brainchild of T. K. Whitaker, recognises that Ireland will have to move away from self-sufficiency toward free trade. It also proposes that foreign firms should be given grants and tax breaks to set up in Ireland.

When Lemass succeeds de Valera as Taoiseach in 1959, Ryan is re-appointed as Minister for Finance. Lemass wants to reward him for his loyalty by also naming him Tánaiste. However, the new leader feels obliged to appoint MacEntee, one of the party elders to the position. Ryan continues to implement the First Programme throughout the early 1960s, achieving a record growth rate of 4 percent by 1963. That year an even more ambitious Second Programme is introduced. However, it overreaches and has to be abandoned. In spite of this, the annual growth rate averages five percent, the highest achieved since independence.

Ryan does not stand in the 1965 Irish general election, after which he is nominated by the Taoiseach to Seanad Éireann, where he joins his son, Eoin Ryan Snr. At the 1969 dissolution he retires to his farm at Kindlestown, County Wicklow, where he dies at age 77 on September 25, 1970. He is buried at Redford Cemetery, Greystones, County Wicklow. His grandson, Eoin Ryan Jnr, serves in the Oireachtas from 1989 to 2007 and later in the European Parliament from 2004 to 2009.