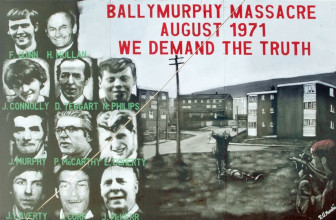

The Ballymurphy Massacre is a series of incidents that take place over a three-day period beginning on August 9, 1971, in which the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment of the British Army kill eleven civilians in Ballymurphy, Belfast, Northern Ireland, as part of Operation Demetrius. The shootings are later referred to as Belfast’s Bloody Sunday, a reference to the killing of civilians by the same battalion in Derry a few months later.

Two years into The Troubles and Belfast is particularly affected by political and sectarian violence. The British Army had been deployed in Northern Ireland in 1969, as events had grown beyond the control of the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

On the morning of Monday, August 9, 1971, the security forces launch Operation Demetrius. The plan is to arrest and intern anyone suspected of being a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. The unit selected for this operation is the Parachute Regiment. Members of the Parachute Regiment state that, as they enter the Ballymurphy area, they are shot at by republicans and return fire.

Mike Jackson, later to become head of the British Army, includes a disputed account of the shootings in his autobiography and his then role as press officer for the British Army stationed in Belfast while the incidents happened. This account states that those killed in the shootings were Republican gunmen. This claim has been strongly denied by the Catholic families of those killed in the shootings, in interviews conducted during the documentary film The Ballymurphy Precedent.

In 2016, Sir Declan Morgan, the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland, recommends an inquest into the killings as one of a series of “legacy inquests” covering 56 cases related to the Troubles.

These inquests are delayed, as funding had not been approved by the Northern Ireland Executive. The former Stormont first minister Arlene Foster of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) defers a bid for extra funding for inquests into historic killings in Northern Ireland, a decision condemned by the human rights group Amnesty International. Foster confirms she had used her influence in the devolved power-sharing executive to hold back finance for a backlog of inquests connected to the conflict. The High Court says her decision to refuse to put a funding paper on the Executive basis was “unlawful and procedurally flawed.”

Fresh inquests into the deaths open at Belfast Coroner’s Court in November 2018 under Presiding Coroner Mrs. Justice Siobhan Keegan. The final scheduled witnesses give evidence on March 2-3, 2020, around the fatal shootings of Father Hugh Mullan and Frank Quinn on waste ground close to an army barracks at Vere Foster school in Springmartin on the evening of August 9. Justice Keegan sets a date of March 20 for final written submissions from legal representatives. A decision is still pending.

The killings are the subject of the August 2018 documentary The Ballymurphy Precedent, directed by Callum Macrae and made in association with Channel 4.

(Pictured: A mural in Belfast commemorating the victims of the Ballymurphy Massacre)